Introduction

Priapism — the persistent, often painful erection of the penis unrelated to sexual arousal — remains one of the more paradoxical and challenging urologic emergencies. While its mythological name derives from the Greek fertility god Priapus, the clinical reality is anything but divine. The condition, particularly the ischemic (low-flow) subtype, can progress swiftly from discomfort to irreversible cavernosal fibrosis and erectile dysfunction (ED) if not managed urgently.

Despite its relative rarity in the general population (an incidence of approximately 1.5 per 100,000 person-years), priapism is alarmingly prevalent among patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) — affecting up to 40% of men and boys with this hematologic disorder. This intersection of urology and hematology has shaped both the understanding and the management of priapism, turning what was once a purely mechanical issue of trapped blood into a molecular disorder of nitric oxide (NO) dysregulation and vascular imbalance.

This article explores the pathophysiology, classification, diagnosis, and management of priapism — with a focus on its ischemic form and its frequent association with SCD. It offers a structured, clinically grounded overview suitable for medical professionals seeking to refine their approach to this intricate condition.

The Case at Hand: A Clinical Snapshot

Consider a typical presentation: a 22-year-old man arrives at the emergency department with a painful erection lasting six hours. There is no sexual stimulation, no pelvic trauma, and only mild exertion preceding onset. He has a history of intermittent episodes resolving spontaneously with oxygen therapy. Physical examination reveals a rigid, tender shaft and a soft, uninvolved glans — classic signs of ischemic priapism.

Blood-gas aspiration confirms the diagnosis: acidosis, hypoxia, and hypercapnia, consistent with stagnant, deoxygenated blood. Further testing identifies hemoglobin SS, confirming sickle cell anemia.

This case distills the challenge: a vascular emergency deeply intertwined with systemic pathology. Immediate decompression through aspiration, irrigation, and intracavernosal phenylephrine injection provides relief, but the risk of recurrence — and eventual ED — lingers. Understanding why it occurs is key to breaking this cycle.

Normal Erection Physiology: The Nitric Oxide–cGMP Axis

Penile erection is, at its core, a story of vascular balance. Under normal circumstances, the penis remains flaccid for most of the day, maintained by sympathetic tone and the constrictive influence of smooth muscle within the corpora cavernosa. When arousal occurs — whether by sensory input, psychogenic stimuli, or nocturnal activation — parasympathetic pathways trigger a cascade of events leading to smooth muscle relaxation and increased arterial inflow.

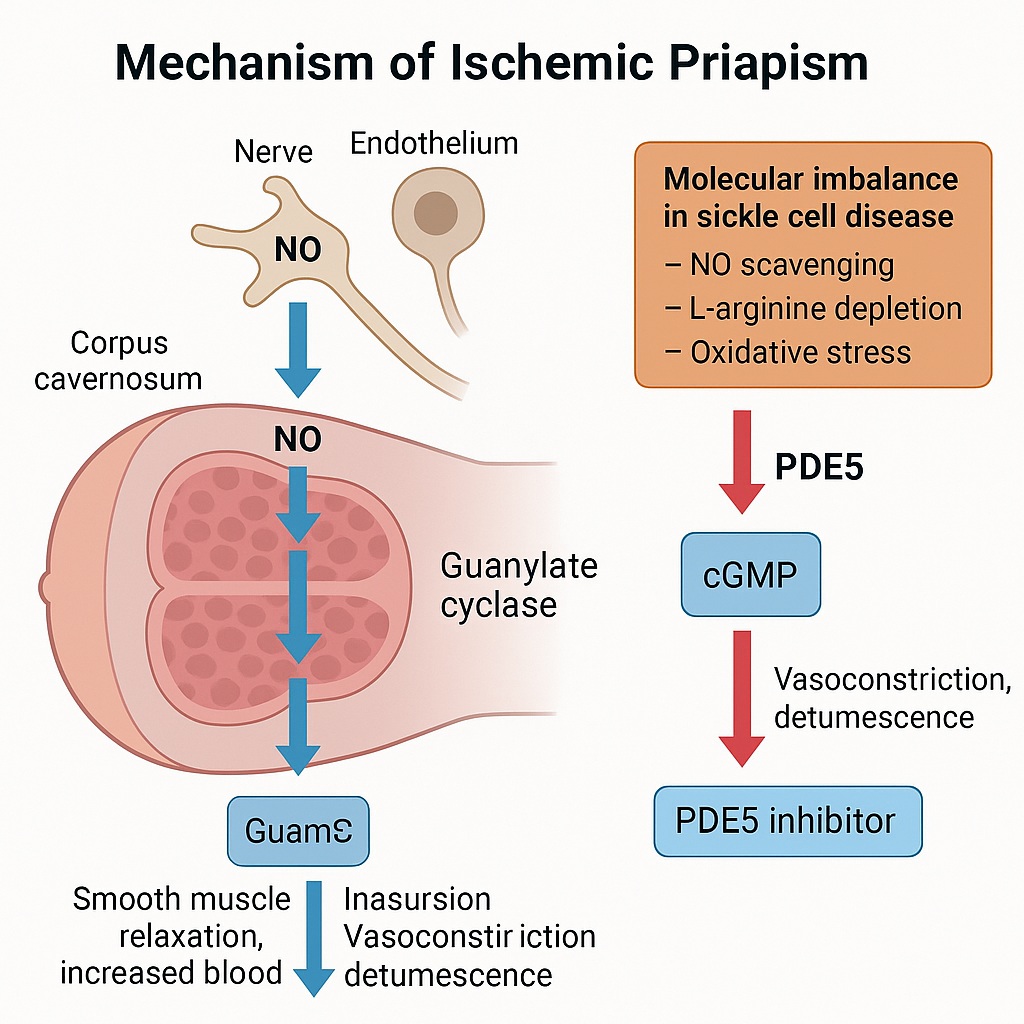

At the molecular level, the process hinges on the nitric oxide (NO)–cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) pathway:

- NO synthesis — Neuronal and endothelial nitric oxide synthases (nNOS and eNOS) convert L-arginine into NO.

- cGMP activation — NO diffuses into smooth muscle cells, activating guanylate cyclase and increasing cGMP levels.

- Vasodilation — cGMP induces relaxation of trabecular smooth muscle, allowing arterial inflow and venous occlusion, producing rigidity.

- Termination — The enzyme phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) hydrolyzes cGMP, restoring tone and detumescence.

In a healthy individual, this finely tuned system permits reversible erection. In priapism, however, the feedback fails — and the erection persists beyond physiology’s control.

Classification and Etiology of Priapism

Priapism is broadly classified into three clinical forms: ischemic, nonischemic, and recurrent ischemic (stuttering).

Ischemic (Low-Flow) Priapism

Accounting for over 95% of all cases, ischemic priapism is a true medical emergency. Venous outflow obstruction leads to hypoxia, acidosis, and compartment-like pressure elevation within the corpora cavernosa. After six hours, tissue necrosis begins; by 24 hours, irreversible fibrosis and 90% risk of permanent ED ensue. The longer the erection, the greater the damage.

Common etiologies include:

- Hematologic disorders (notably SCD, thalassemia, G6PD deficiency)

- Medications (antipsychotics, antidepressants, antihypertensives, and vasoactive erectile agents)

- Substance use (alcohol, cocaine, marijuana)

- Trauma and infection

- Neoplasms and metabolic conditions

In SCD, hemolysis releases free hemoglobin and arginase, both of which scavenge NO or deplete its precursor, L-arginine — setting the stage for NO imbalance and dysregulated cavernosal tone.

Recurrent (Stuttering) Priapism

Recurrent ischemic priapism (RIP) is the most insidious variant, defined by repeated short-lived episodes of painful erections. Each event may last less than three hours and resolve spontaneously, yet cumulative ischemic injury leads to fibrosis and progressive erectile decline. Roughly one-third of RIP cases progress to major ischemic episodes.

In SCD, chronic PDE5 downregulation and reduced basal NO availability make the penis prone to uncontrolled erections upon stimulation. Over time, the system loses its “off switch.”

Nonischemic (High-Flow) Priapism

This rare variant stems from unregulated arterial inflow, often due to trauma-induced fistula formation between cavernosal arteries and sinusoids. Unlike ischemic priapism, the penis is tumescent but non-rigid and painless. Blood gases show oxygenated profiles, and Doppler ultrasonography reveals high arterial velocities. These cases are often self-limiting, requiring conservative or minimally invasive management.

Molecular Pathophysiology: When Nitric Oxide Goes Silent

The historical belief that priapism was merely a consequence of erythrocyte sludging and vascular stasis has evolved. Contemporary research reveals a molecular vascular dysfunction, particularly within SCD.

In SCD, chronic hemolysis depletes NO through multiple mechanisms:

- NO scavenging by free hemoglobin released during hemolysis.

- L-arginine depletion via arginase release from lysed red cells.

- Oxidative stress, producing reactive oxygen species that inhibit NO synthase activity.

The result is impaired endothelial NO production, leading to chronically low basal levels of PDE5. Without adequate PDE5, cGMP accumulates unchecked during neural stimulation, perpetuating sustained vasodilation and priapic episodes.

Additional pathways involving RhoA/ROCK, adenosine, and opiorphin signaling further modulate smooth muscle tone and are now considered promising therapeutic targets.

Diagnosis: A Race Against Ischemia

Timely and accurate differentiation between ischemic and nonischemic priapism is essential, as management strategies diverge dramatically.

History and Physical Examination

Pain severity and duration provide crucial diagnostic clues. Severe pain and rigidity suggest ischemia. Clinicians should document duration, triggering events, medications, prior episodes, and comorbidities. Physical examination distinguishes rigid corpora cavernosa with a soft glans (ischemic) from partially tumescent, painless erections (nonischemic).

Laboratory Assessment

Corporal blood gas analysis is diagnostic gold:

- pH < 7.25

- pO₂ < 30 mmHg

- pCO₂ > 60 mmHg

These parameters confirm ischemia. Additional workup includes hemoglobin electrophoresis for SCD, toxicology screening for drug causes, and coagulation panels when indicated.

Imaging

Color duplex ultrasonography provides functional visualization: absent or minimal flow confirms ischemia; high flow velocities indicate nonischemic variants. In rare cases, arteriography assists in locating arteriovenous fistulas for embolization planning.

Management: A Stepwise Clinical Algorithm

The management of priapism requires a structured, escalating approach, progressing from least to most invasive intervention. The goals are clear: relieve pain, decompress cavernosal compartments, restore blood flow, and prevent ED.

Step 1: Initial Measures

Before reaching the hospital, patients often attempt conservative techniques — exercise, ejaculation, hydration, or warm baths. These may help in early episodes but should never delay medical care.

In the clinical setting:

- Provide analgesia (e.g., morphine).

- Administer supplemental oxygen for SCD-related hypoxia.

- Initiate intravenous hydration and, if appropriate, exchange transfusion (though evidence for efficacy is limited and neurologic risks have been reported).

Step 2: Aspiration and Irrigation

The cornerstone of emergency management is corporal aspiration.

A 16- or 18-gauge needle is inserted into the corpus cavernosum at the proximal lateral shaft to drain dark, deoxygenated blood. Saline irrigation follows, promoting clearance of acidic metabolites and pressure relief. Detumescence rates approach 30% with aspiration alone.

Step 3: Sympathomimetic Injection

If aspiration fails, intracavernosal phenylephrine — a selective α₁-adrenergic agonist — is administered in 100–200 µg aliquots every five minutes (up to 1 mg/hour). Phenylephrine induces smooth muscle contraction, reestablishing venous outflow. Success rates reach 80% when combined with aspiration. Continuous monitoring for hypertension or arrhythmia is essential, particularly in high-risk patients.

Step 4: Surgical Shunting

When pharmacologic interventions fail after one hour (or priapism persists >72 hours), surgical options become necessary. Shunting procedures create alternative pathways for blood drainage by connecting the corpora cavernosa to the glans, corpus spongiosum, or venous system.

- Distal shunts (Winter, Ebbehoj, or T-shunt) are preferred for simplicity and fewer complications.

- Proximal shunts are reserved for refractory cases and carry higher risks, including infection, cavernositis, or urethral fistula.

If detumescence remains incomplete, early penile prosthesis implantation (within 72 hours) may be considered to prevent fibrosis and preserve penile length — a decision requiring transparent patient counseling.

Chronic and Preventive Management

Low-Dose PDE5 Inhibitor Therapy

Counterintuitive as it may seem, daily low-dose PDE5 inhibitors (e.g., sildenafil 50 mg once daily, unrelated to sexual activity) can prevent recurrent ischemic priapism. By restoring basal PDE5 activity and NO balance, this approach normalizes cavernosal homeostasis. Trials demonstrate safety and modest efficacy, though adherence and cost remain obstacles.

Hormonal Modulation

Antiandrogenic therapy (ketoconazole, leuprolide, or estrogens) has been historically used to reduce episodes by lowering testosterone levels. However, these regimens carry significant side effects — decreased libido, gynecomastia, delayed puberty — and are unsuitable for men desiring fertility.

Conversely, testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) may benefit hypogonadal men with SCD, potentially restoring normal NOS and PDE5 regulation. This shift in paradigm underscores the complexity of hormonal involvement in penile physiology.

Hydroxyurea Therapy

As the mainstay of SCD management, hydroxyurea increases fetal hemoglobin and reduces hemolysis, indirectly improving NO bioavailability. Its role in priapism prevention remains anecdotal but mechanistically promising, functioning also as a mild NO donor.

Other Investigational Strategies

Emerging research explores:

- NO-releasing compounds to restore endothelial signaling.

- Adenosine deaminase replacement to modulate adenosine-mediated vasodilation.

- Ornithine decarboxylase inhibitors targeting opiorphin-related pathways.

These molecularly tailored therapies offer hope for long-term prophylaxis beyond symptom management.

The Multidisciplinary Imperative

Effective priapism management requires integration of urology, hematology, and emergency medicine. For SCD patients, education is pivotal — early presentation dramatically improves outcomes. Chronic care should emphasize:

- Patient awareness of early warning signs.

- Access to phenylephrine autoinjection training for self-management of minor episodes.

- Regular follow-up to monitor erectile function, endocrine status, and psychological well-being.

Psychosocial consequences, including anxiety, depression, and sexual stigma, warrant as much attention as physical recovery. True success in priapism management lies in preserving not just anatomy, but dignity and confidence.

Future Perspectives

The landscape of priapism treatment is shifting from reactive emergency care to preventive molecular therapy. The recognition that priapism is not simply a vascular accident but a chronic biochemical disorder has transformed research directions.

Potential breakthroughs include:

- Sustained NO donors capable of correcting endothelial dysfunction at the source.

- Gene-targeted therapies modulating PDE5 or adenosine receptor expression.

- Personalized medicine models integrating genetic polymorphisms linked to vascular tone regulation.

Ultimately, progress will depend on cross-disciplinary collaboration, combining insights from vascular biology, hematology, and sexual medicine to translate bench findings into bedside protocols.

Conclusion

Priapism, once viewed as an obscure urologic emergency, has emerged as a molecularly defined vascular disorder demanding precision medicine. Its association with SCD reveals a compelling intersection between hematologic and endothelial pathology.

Early recognition, prompt decompression, and thoughtful preventive strategies — from PDE5 modulation to hormonal balance and NO restoration — define modern management. Yet, the true frontier lies in prevention: harnessing molecular insight to stop priapism before it starts.

In short, treating priapism requires both urgency and nuance — the immediate skill of a surgeon and the long view of a molecular biologist. The goal is not merely to end an erection, but to restore control, confidence, and quality of life.

FAQ: Key Clinical Questions

1. Why is ischemic priapism considered an emergency?

Because cavernosal hypoxia and acidosis rapidly lead to smooth muscle necrosis. After 4–6 hours, tissue damage becomes significant; after 24 hours, irreversible fibrosis and erectile dysfunction are almost inevitable.

2. Can phosphodiesterase inhibitors like sildenafil really prevent priapism?

Yes, paradoxically. Low-dose daily PDE5 inhibitor therapy helps reestablish baseline enzyme activity and NO–cGMP balance, reducing recurrence in recurrent ischemic priapism, particularly in sickle cell disease.

3. When should surgical shunting or prosthesis implantation be considered?

If detumescence fails after aspiration, irrigation, and sympathomimetic therapy, surgical shunting is warranted. For episodes persisting beyond 72 hours, early penile prosthesis implantation should be discussed to prevent fibrosis and preserve length.