Introduction

In the evolving landscape of chronic pain management, opioid analgesics remain both indispensable and controversial. Their widespread use for non-cancer pain—particularly low back pain, the most common musculoskeletal complaint worldwide—reflects a therapeutic paradox. While opioids promise relief, they frequently extract physiological costs that extend far beyond the nociceptive system. Among the most insidious of these is sexual dysfunction, a complication that remains under-recognized, under-discussed, and often unacknowledged by both patient and physician.

The landmark study by Richard Deyo and colleagues (2013) brings empirical clarity to this issue. Using a large health maintenance organization (HMO) database of over 11,000 men with back pain, the investigators explored how long-term and high-dose opioid therapy correlates with the use of medications for erectile dysfunction (ED) and testosterone replacement. Their findings illuminate an often overlooked truth: chronic opioid exposure can quietly erode male sexual function, not only through opioid-induced hypogonadism, but also via a complex interplay of psychological, vascular, and metabolic mechanisms.

This article revisits their findings with a translational clinical lens, tracing the path from neuroendocrine disruption to clinical decision-making—and asking a simple but consequential question: Is pain relief worth the hormonal price?

The Intersection of Pain, Opioids, and Sexual Function

Pain, depression, and sexual dysfunction are familiar bedfellows. Chronic back pain disrupts physical function, sleep, and self-image—each a known contributor to diminished libido and erectile performance. Depression, often coexisting with chronic pain, compounds this effect. Meanwhile, opioids, once introduced into this milieu, can further dampen sexual health through neuroendocrine suppression and vascular impairment.

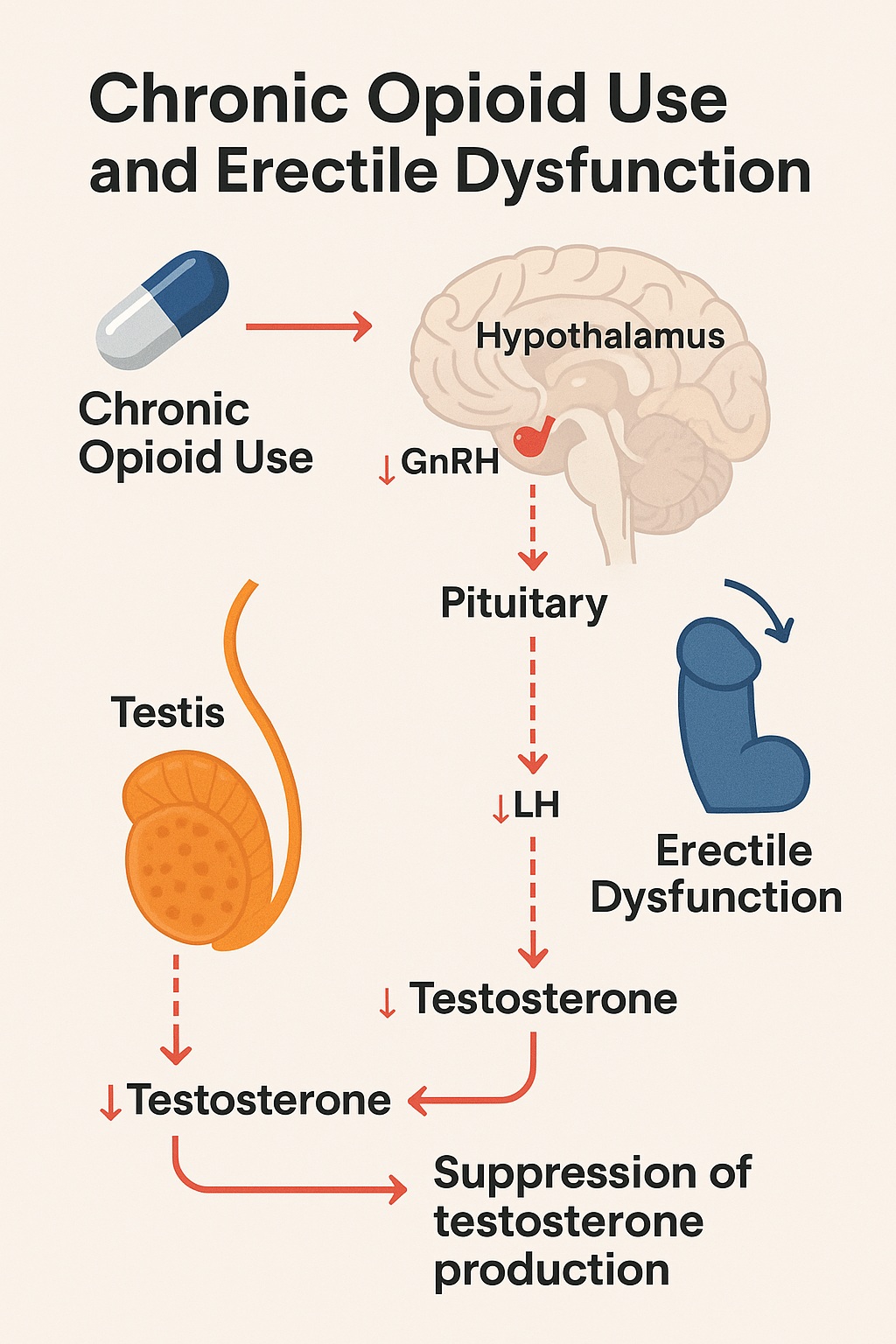

Physiologically, the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal (HPG) axis is exquisitely sensitive to opioid interference. By binding to μ-opioid receptors in the hypothalamus, opioids suppress gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion, leading to downstream reductions in luteinizing hormone (LH) and testosterone. The result is opioid-induced androgen deficiency (OPIAD)—a clinical syndrome characterized by fatigue, mood disturbances, and sexual dysfunction.

Yet, as Deyo et al. emphasized, the problem is not simply hormonal. Smoking, obesity, comorbid illness, and concomitant sedative-hypnotic use all exacerbate sexual dysfunction. The overlap between opioid exposure and these risk factors makes teasing out causality challenging, but the association remains consistent: the longer and stronger the opioid regimen, the higher the risk of erectile or androgenic impairment.

This intersection of physiology and pharmacology underscores a broader reality of chronic pain care: no system operates in isolation. Treating pain often means disrupting the subtle endocrine balance that sustains vitality and intimacy.

Study Overview: Back Pain, Opioids, and Erectile Dysfunction in the Real World

Deyo’s team conducted a cross-sectional analysis of male HMO members aged 18 and older who sought care for back pain in 2004. The researchers reviewed medical and pharmacy records for six months before and after the index visit, classifying opioid exposure into four categories:

- None

- Acute (≤90 days)

- Episodic (>90 days but <120 days)

- Long-term (≥120 days or >90 days with ≥10 refills)

They then tracked prescriptions for erectile dysfunction medications (sildenafil, tadalafil, vardenafil) and testosterone replacement therapy (TRT), using these as proxies for clinically significant sexual dysfunction. Covariates included age, comorbidity (via RxRisk score), depression, smoking status, and sedative-hypnotic use.

The Population in Focus

Of 11,327 men, 909 (8%) received medications for ED or testosterone replacement within the observation window. Compared with those who did not, these men were:

- Older (mean 55.7 vs. 48.0 years),

- More medically complex,

- More likely to have depression,

- More likely to use sedative-hypnotics, and

- More likely to be smokers or former smokers.

These patterns mirror real-world clinical practice: men prescribed chronic opioids often sit at the crossroads of pain, polypharmacy, and comorbidity, forming a population uniquely vulnerable to endocrine disruption.

The Dose–Duration Dilemma: Opioids as Endocrine Suppressors

The most striking observation from the study was a dose–response relationship between opioid exposure and markers of sexual dysfunction. As opioid duration and dose increased, so did the probability of receiving treatment for erectile or testosterone deficiency.

- 13.1% of men on long-term opioids received prescriptions for ED or testosterone therapy.

- Among those using ≥120 mg morphine-equivalent daily, the rate rose to 19%, compared to 6.7% among non-opioid users.

- After adjusting for age, comorbidity, and depression, long-term opioid users had 45% higher odds of needing ED or testosterone therapy (OR 1.45, p<0.01).

- High-dose users retained a significant association (OR 1.58, p<0.05) even when duration was controlled for.

Interestingly, short-acting versus long-acting opioid formulations did not significantly differ in risk, implying that total exposure—not pharmacokinetic profile—drives endocrine suppression.

This pattern aligns with prior mechanistic research demonstrating that chronic opioid exposure disrupts GnRH pulsatility and blunts Leydig cell testosterone synthesis. The suppression is both dose-dependent and reversible upon opioid cessation—though recovery may take months.

From a clinical standpoint, this dose–duration relationship offers a clear message: the endocrine system keeps score. The longer opioids are used, and the higher the dose, the louder the hormonal consequences.

Depression, Sedatives, and the Hidden Confounders

The study revealed that depression (OR 1.30) and sedative-hypnotic use (OR 1.30) independently predicted ED medication use. Both findings are clinically intuitive and diagnostically complicating.

Depression itself is a potent suppressor of libido and erectile performance, mediated by both psychological and neurochemical mechanisms (notably serotonergic and dopaminergic imbalance). Moreover, antidepressant pharmacotherapy—especially selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—can further impair sexual function, creating a diagnostic loop in which it is difficult to discern whether opioids, depression, or antidepressants bear the greater blame.

Similarly, sedative-hypnotics such as benzodiazepines depress central arousal and testosterone levels. They often cohabit prescriptions with opioids, particularly in patients with pain-related insomnia or anxiety. The resulting polypharmacy magnifies not only the risk of respiratory depression, but also of sexual and emotional flattening—a quiet collateral of pharmacologic comfort.

Together, these findings highlight an important principle in pain management: biopsychosocial interactions outnumber pharmacologic intentions. Opioid endocrinopathy rarely acts alone; it is amplified by mood disorders, lifestyle factors, and drug–drug synergies.

Mechanistic Pathways: From Receptor to Relationship

To understand opioid-induced sexual dysfunction, one must trace the biochemical cascade that begins at the μ-opioid receptor and ends in the bedroom.

Neuroendocrine Suppression

Opioids inhibit the hypothalamic secretion of GnRH, which in turn suppresses LH and FSH, leading to decreased testosterone in men. This state—opioid-induced hypogonadotropic hypogonadism—results in reduced libido, erectile dysfunction, and infertility.

Vascular Impairment

Chronic opioids impair endothelial function through increased oxidative stress and decreased nitric oxide bioavailability, blunting the very pathway exploited by PDE5 inhibitors like sildenafil. Thus, even when pharmacologic correction is attempted, the underlying endothelial dysfunction limits success.

Central Desensitization

Opioid-induced depression of dopaminergic tone within the mesolimbic reward circuit diminishes sexual motivation and pleasure, converting desire into detachment.

These overlapping pathways render the problem multidimensional: part hormonal, part vascular, part neurochemical. The result is not merely erectile failure, but an erosion of vitality and intimacy, quietly attributed to aging or stress rather than pharmacologic consequence.

Clinical Translation: Lessons for the Pain Specialist

The clinical implications of Deyo’s findings are profound and pragmatic. Pain management must no longer be viewed as a trade of nociception for numbness—it is a systemic intervention with endocrine consequences.

1. Screening and Dialogue

Sexual health should be a routine component of opioid risk assessment. Men beginning long-term opioid therapy should be counseled on potential endocrine effects, including reduced libido, fatigue, and infertility. Asking “How’s your energy and intimacy?” may uncover far more than a testosterone test alone.

2. Monitoring and Mitigation

Regular serum testosterone monitoring is prudent for men on high-dose or long-term opioids. When hypogonadism is confirmed, options include:

- Tapering or discontinuing opioids if feasible

- Switching to non-opioid analgesics or partial agonists (e.g., buprenorphine)

- Initiating testosterone replacement therapy under endocrinologic guidance

3. Integrated Care Approach

Given the multifactorial nature of sexual dysfunction, treatment should integrate psychiatric, endocrine, and behavioral strategies, addressing depression, sleep hygiene, and relationship stressors in parallel.

By framing sexual dysfunction not as an embarrassing side effect but as a vital sign of systemic health, clinicians can foster a more holistic model of chronic pain care—one that values quality of life alongside pain relief.

The Broader Context: Opioids, Masculinity, and Modern Medicine

There is an understated irony in this story. The same class of drugs that promise power over pain also undermine the very hormones that define male vitality. Opioid-induced hypogonadism transforms pain management from a physical intervention into a subtle reconfiguration of identity and desire.

From an epidemiologic perspective, the implications ripple beyond the individual. As opioid prescribing remains prevalent for chronic low back pain—despite limited evidence for long-term benefit—millions of men may unknowingly trade sexual function for analgesia. Yet because sexual side effects are seldom queried or volunteered, the scope of the problem remains largely invisible.

Culturally, this silence reflects the lingering discomfort around discussing sexual health in the context of pain medicine. The data from Deyo et al. make one thing clear: what we don’t ask, we don’t see. And what we don’t see, we don’t manage.

Limitations and Research Directions

As with any cross-sectional study, causation cannot be inferred. Erectile dysfunction or testosterone therapy may predate opioid use, and unmeasured confounders—such as diabetes or vascular disease—may contribute. However, the dose–response gradient strongly supports a biological link rather than mere correlation.

Future studies should pursue:

- Longitudinal cohorts measuring hormone levels pre- and post-opioid exposure,

- Randomized deprescribing trials assessing reversibility of sexual dysfunction, and

- Mechanistic imaging or molecular analyses linking opioid receptor activity to gonadal hormone suppression.

Moreover, exploring gender differences in opioid endocrinopathy remains a critical frontier, as women may experience distinct but equally debilitating reproductive consequences.

Conclusion

The work of Deyo and colleagues reframes long-term opioid therapy as an endocrine as well as analgesic intervention. It challenges clinicians to see beyond pain scores and functional questionnaires—to consider the hormonal and relational costs of chronic opioid use.

In men with back pain, sexual dysfunction is not merely a comorbidity—it is a biomarker of systemic opioid toxicity. Recognizing and addressing it may not only restore sexual health but also improve mood, energy, and even pain tolerance, given testosterone’s role in central nociception modulation.

As medicine moves toward personalized pain care, one principle should guide practice: treat pain, but not at the expense of vitality. If the price of comfort is the quiet fading of desire, perhaps it is time to rethink what “quality of life” truly means.

FAQ: Opioids, Back Pain, and Erectile Dysfunction

1. Do opioids directly cause erectile dysfunction?

Yes. Chronic opioid use suppresses testosterone production by inhibiting the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. This endocrine suppression leads to reduced libido, erectile difficulties, and fatigue. The effect is dose- and duration-dependent.

2. Can erectile function recover after stopping opioids?

Often, yes. Testosterone and sexual function typically improve within weeks to months after opioid discontinuation or dose reduction, though the timeline varies. In some cases, testosterone replacement therapy may be needed during recovery.

3. Should men on long-term opioids be screened for hormonal changes?

Absolutely. Baseline and periodic testosterone assessments, combined with open discussions about sexual health, should be standard in chronic pain management. Early recognition allows timely intervention—whether by adjusting therapy or initiating hormonal support.