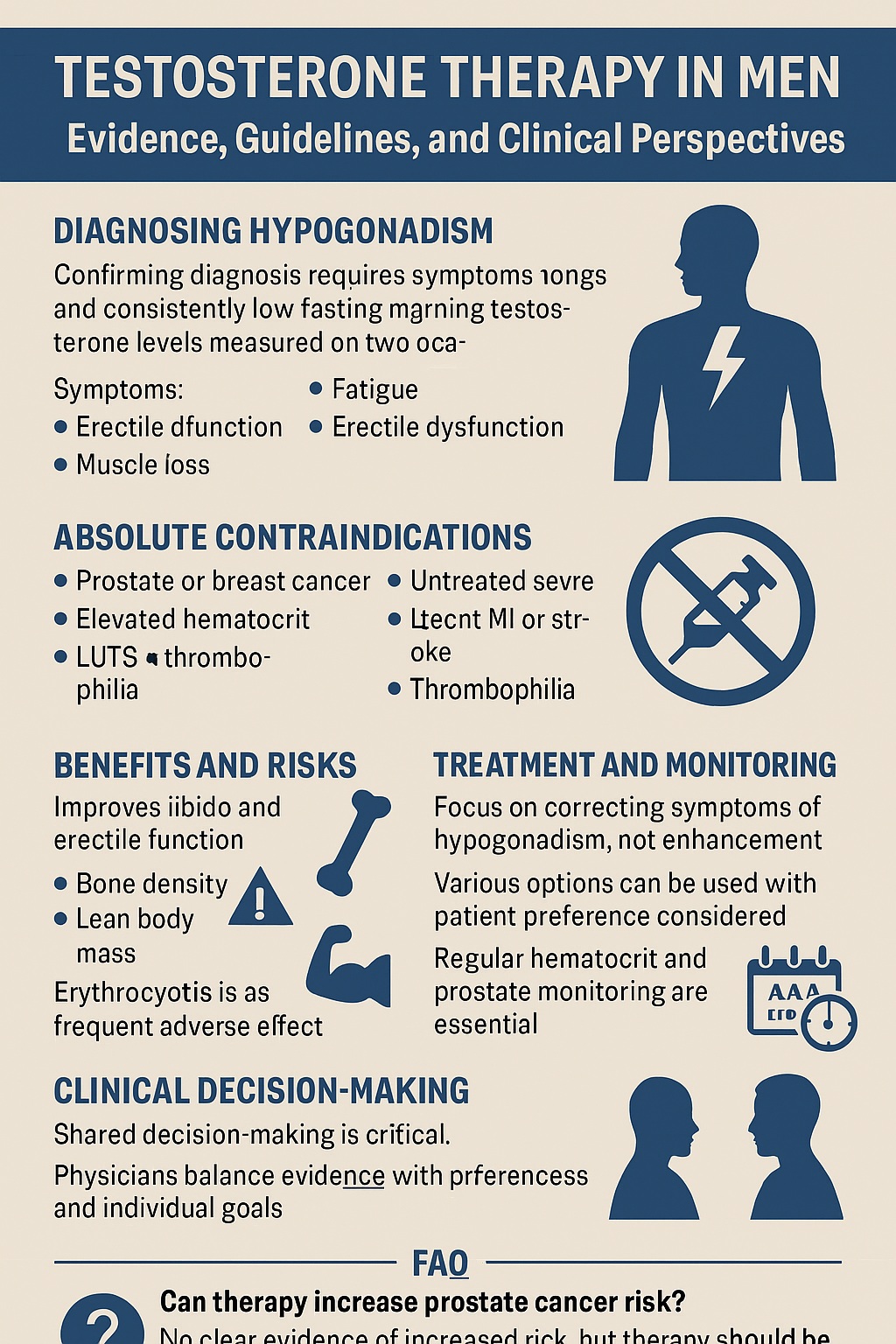

Introduction

Testosterone, often portrayed as the symbol of masculinity and vitality, is in reality a tightly regulated hormone with profound effects on nearly every system of the male body. Its decline, whether due to congenital defects, acquired diseases, or functional suppression, manifests in ways that affect sexual health, physical strength, bone integrity, and overall quality of life. Physicians are often confronted with men who present fatigue, low libido, muscle loss, or mood disturbances, and the question arises: is testosterone therapy the answer, or merely a fashionable prescription?

The Endocrine Society’s 2018 clinical practice guideline provides a rigorous, evidence-based framework for answering that question . But guidelines are not novels. They are precise, dense, and sometimes more intimidating than enlightening. The purpose of this article is to translate that evidence into an engaging yet strictly professional narrative, to clarify who benefits from testosterone therapy, who should avoid it, and how to navigate the fine line between treatment and risk.

Defining Hypogonadism: The Biological Core

Hypogonadism is not simply “low testosterone.” It is a clinical syndrome defined by both symptoms and unequivocally low serum testosterone concentrations. The hormone may be diminished because of primary testicular failure (primary hypogonadism) or hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction (secondary hypogonadism) . Occasionally, both ends of the axis are impaired, leading to combined forms.

Primary hypogonadism is often irreversible: genetic syndromes such as Klinefelter’s, chemotherapy-induced gonadal damage, cryptorchidism, or orchitis all belong here. Secondary hypogonadism, however, can be organic (e.g., pituitary tumors, infiltrative disease) or functional—conditions like obesity, opioid use, or systemic illness that suppress gonadotropins in a potentially reversible fashion .

The distinction matters. A man with a prolactin-secreting adenoma needs dopamine agonist therapy, not testosterone injections. Conversely, a man with irreversible testicular failure may require lifelong replacement. Understanding etiology is therefore not academic hair-splitting but the bedrock of personalized treatment.

The Art and Science of Diagnosis

The guideline insists on precision. Diagnosis of hypogonadism requires two separate morning fasting measurements of total testosterone using standardized assays. Testosterone is a fickle hormone: levels fluctuate with circadian rhythm, food intake, illness, and laboratory methodology. Acting on a single borderline reading is a common and avoidable mistake.

In cases where total testosterone is near the lower limit of normal or in men with altered sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG), free testosterone measurement is recommended, preferably via equilibrium dialysis or reliable calculations. Direct analog immunoassays, unfortunately still popular in some laboratories, are deemed inaccurate and should be abandoned.

Equally critical is the context: symptoms such as erectile dysfunction, infertility, anemia, or decreased bone mineral density must be present. Asymptomatic men with “low T” on paper do not qualify for therapy, regardless of how persuasive the advertisement for testosterone gels may appear.

Whom Not to Treat: Absolute and Relative Contraindications

The allure of testosterone is powerful, but caution is paramount. The guideline firmly recommends against testosterone therapy in men with the following conditions :

- Active breast or prostate cancer

- Palpable prostate nodule or induration without urological clearance

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) above 4 ng/mL (or above 3 ng/mL in high-risk men) without evaluation

- Elevated hematocrit

- Untreated severe obstructive sleep apnea

- Severe lower urinary tract symptoms

- Uncontrolled heart failure

- Recent myocardial infarction or stroke (within 6 months)

- Known thrombophilia

Men planning fertility should also avoid testosterone, as exogenous replacement suppresses spermatogenesis. For them, gonadotropin therapy or alternative strategies are the appropriate path.

Treatment Principles: Restoring, Not Enhancing

When the diagnosis is secure, and contraindications are absent, testosterone therapy can be life-changing. The goal is not to create supermen, but to induce and maintain secondary sex characteristics and correct symptoms of deficiency . This includes restoration of libido, improvement of muscle and bone health, and stabilization of mood and energy.

Multiple formulations are available: injectable esters, long-acting undecanoate, transdermal gels and patches, subcutaneous pellets, and oral options in certain countries . Each has pharmacokinetic quirks—injectables produce peaks and troughs, gels offer smoother profiles but require daily compliance, and pellets last months but necessitate minor surgery. Choice depends on patient preference, access, and tolerance.

Efficacy is well documented. Randomized controlled trials show improvements in sexual function, lean body mass, bone mineral density, and anemia . Gains in strength and physical function are more modest, and effects on mood or cognition remain inconsistent. The therapy is not a panacea, but it is far from placebo.

Special Populations: The Nuances of Indication

The guideline wisely avoids one-size-fits-all prescriptions. Certain patient groups warrant particular discussion:

Older Men with Age-Related Low Testosterone

Aging is accompanied by gradual declines in total and free testosterone. Yet the guideline advises against routinely prescribing testosterone to all men over 65 with low concentrations . For symptomatic men with unequivocally low levels, individualized therapy may be considered, but the balance between modest benefits (sexual function, anemia, bone density) and uncertain long-term risks demands careful shared decision-making.

HIV-Infected Men with Weight Loss

Low testosterone is prevalent in HIV-infected men, contributing to frailty, wasting, and depression. Here, the guideline suggests short-term testosterone therapy if other causes of weight loss are excluded . Clinical trials demonstrate small but meaningful gains in lean body mass and strength, though long-term safety remains unproven.

Men with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Despite the strong association between diabetes and low testosterone, the guideline recommends against testosterone therapy as a means to improve glycemic control. Any metabolic benefit is inconsistent, and therapy should not be sold as a diabetes treatment.

Monitoring: Vigilance Beyond Prescription

Starting therapy is not the end of the story but the beginning of a long-term relationship. The guideline underscores structured follow-up :

- Evaluate response, side effects, and compliance within months of initiation.

- Monitor hematocrit to avoid erythrocytosis, the most frequent adverse effect.

- Assess PSA and perform urological consultation if values rise significantly within the first year.

- After one year, prostate monitoring should align with standard cancer screening appropriate for age and risk.

Beyond laboratory vigilance, clinicians must listen. Improvements in energy or sexual function may take time, and unrealistic expectations often lead to premature discontinuation. Conversely, patients reporting excessive acne, breast tenderness, or irritability may need dose adjustments.

Benefits: What the Evidence Actually Shows

Testosterone therapy consistently improves sexual function, libido, and erectile function in hypogonadal men . It increases lean body mass, reduces fat mass, and augments bone density . Anemia responds robustly, with hemoglobin increases of clinical significance.

Mood improvements are modest, and cognitive effects largely absent. Physical performance gains exist but fall short of athletic fantasies. Importantly, testosterone does not cure everything: it is not a treatment for depression, osteoporosis in eugonadal men, or diabetes.

Risks: Separating Myth from Reality

The specter of prostate cancer and cardiovascular events haunts every discussion of testosterone therapy. The guideline acknowledges that evidence is inconclusive . Randomized trials have not demonstrated statistically significant increases in prostate cancer or major cardiovascular events, but they are underpowered for rare outcomes. Observational studies yield conflicting results, fueling ongoing controversy.

What is clear is the risk of erythrocytosis, particularly with injectable formulations . Elevated hematocrit increases the risk of thrombotic events and must be managed by dose adjustment, formulation switch, or phlebotomy. Other side effects—acne, sleep apnea exacerbation, breast tenderness—are usually manageable but require awareness.

The bottom line is that testosterone therapy is neither a harmless fountain of youth nor a guaranteed path to disease. It is a therapy with measurable benefits and manageable risks, provided that guidelines are respected.

Clinical Decision-Making: The Shared Path

Perhaps the most valuable contribution of the guideline is its emphasis on shared decision-making . Physicians must balance evidence with patient preferences, explain uncertainties honestly, and tailor treatment to individual goals. For some men, restoring libido and muscle strength justifies the therapy despite unclear long-term risks. For others, lifestyle interventions, management of comorbidities, or treatment of depression may be more appropriate than hormonal replacement.

Conclusion

Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism is not an indulgence but a legitimate medical intervention when properly indicated. Its benefits—sexual, hematologic, skeletal, and muscular—are tangible. Its risks—primarily erythrocytosis and uncertain long-term effects—are real but manageable with vigilance.

The key is precision: correct diagnosis, thoughtful exclusion of contraindications, individualized treatment, and rigorous monitoring. Misused, testosterone is hype; applied correctly, it is healing. The clinician’s task is to discern the difference.

FAQ

1. Can testosterone therapy increase the risk of prostate cancer?

Current evidence does not confirm that testosterone therapy increases prostate cancer risk. However, men with known or suspected prostate cancer should not receive therapy, and regular prostate monitoring is essential during treatment .

2. How quickly do patients feel benefits after starting therapy?

Improvements in libido may occur within weeks, while changes in muscle mass, bone density, and anemia may take months. Patience and adherence are critical to evaluate true benefits.

3. Is testosterone therapy safe for older men with mildly low levels?

Routine treatment of all older men is not recommended. For symptomatic men with unequivocally low testosterone, individualized therapy may be offered after discussing risks and benefits, but long-term safety data remain limited .