Introduction

Few hormones in human biology have sparked as much fascination, debate, and misunderstanding as testosterone. For decades, it has been celebrated as the quintessential “male hormone,” associated with virility, libido, muscle mass, and bone strength. In recent years, however, testosterone has found new clinical roles—not only in the management of hypogonadism in men but also in postmenopausal women for restoring sexual desire.

Yet, despite its expanding prescription, a fundamental concern remains unresolved: what is the true impact of testosterone supplementation on cardiovascular and renal health in aging individuals?

Emerging evidence indicates that testosterone is neither a harmless elixir of youth nor an unqualified villain. It is a hormone with complex interactions—capable of restoring quality of life while also potentially accelerating hypertension, renal injury, and vascular dysfunction. This duality calls for careful scientific appraisal, far beyond simplistic promises of “anti-aging” therapies.

The Age-Related Decline of Testosterone

Testosterone decline in men is a gradual, almost imperceptible process. By the age of 65, over 60% of otherwise healthy men have free testosterone levels below the physiological range of younger adults. This drop stems from combined testicular and hypothalamic–pituitary dysfunction and occurs regardless of obesity or chronic illness.

In women, the trajectory is more complex. While serum testosterone is naturally lower, data on postmenopausal levels remain conflicting. Some studies suggest a decrease, others an increase, and some stability. Natural menopause often creates a relatively hyperandrogenic state compared with the steep decline in estrogen, whereas surgical menopause results in persistently lower androgen levels. The ovarian stroma, through hyperplasia, continues to produce testosterone in some women, explaining variability across populations.

Thus, both sexes experience aging-associated changes in testosterone, but with different trajectories and clinical implications.

Why Testosterone Supplementation Has Become Popular

The rationale for testosterone replacement in aging men and women is straightforward, if somewhat seductive.

- In men: therapy promises improvements in muscle mass, bone density, libido, mood, and erectile function (often combined with PDE5 inhibitors).

- In women: the main indication is restoration of sexual desire and quality of life after menopause.

In both groups, testosterone is easily available—sometimes over-the-counter in the form of androstenedione and related compounds. Serum levels achieved with supplementation can vary dramatically, ranging from physiological to supraphysiological (up to 16-fold higher than normal).

This increasing use has far outpaced rigorous clinical testing. While physicians are cautious about prostate cancer risk in men and cardiovascular complications in women, long-term data on cardiovascular and renal safety remain strikingly scarce.

Testosterone and Blood Pressure Regulation

Blood pressure differences between sexes hint at testosterone’s role in vascular physiology. Men generally exhibit higher blood pressure than women until menopause, after which the gap narrows or even reverses. Curiously, hypertensive men tend to have lower serum testosterone than normotensive peers, raising questions about whether testosterone deficiency is protective or harmful.

Animal studies clarify some of this ambiguity. In spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR), males develop higher blood pressure after puberty compared with females. Castration normalizes their blood pressure, while testosterone administration restores hypertension. Similar patterns appear in salt-sensitive models, where testosterone amplifies salt-induced hypertension.

Mechanistically, testosterone promotes renal sodium and water reabsorption, augments activity of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), and increases vascular responsiveness to vasoconstrictors. The net effect: higher glomerular pressures and systemic hypertension.

Thus, in aging humans, supplementing testosterone could potentially worsen blood pressure control, particularly in those predisposed to salt sensitivity or metabolic syndrome.

Testosterone and Renal Function

The kidney is not merely a passive target of hormones; it can synthesize androgens de novo. Enzymes such as 17α-hydroxylase and 3β-HSD are expressed in renal tissue, allowing local production of testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Androgen receptors are widely distributed in the proximal tubules and collecting ducts.

Chronic testosterone exposure increases proximal tubule reabsorption of sodium and water, raising intraglomerular pressure. While acute testosterone may transiently vasodilate renal vessels, chronic exposure shifts the balance toward vasoconstriction, hypertrophy, and injury.

Epidemiological and experimental evidence points to faster progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in men than women, even after adjusting for blood pressure. Castration or androgen blockade attenuates renal injury in hypertensive and nephropathy models. Conversely, testosterone supplementation accelerates glomerulosclerosis, proteinuria, and decline in glomerular filtration rate (GFR).

This suggests that testosterone is not merely a bystander but an active promoter of renal disease, particularly in the aging male kidney.

The Renin–Angiotensin System, Endothelin, and Testosterone

One of testosterone’s most insidious effects lies in its ability to amplify vasoconstrictor systems.

- Renin–Angiotensin System (RAS): Testosterone upregulates renin and angiotensinogen gene expression in kidneys, enhances angiotensin II responsiveness, and raises plasma renin activity. These changes magnify salt sensitivity and glomerular hypertension.

- Endothelin: Testosterone stimulates endothelin-1 production, a potent vasoconstrictor and promoter of fibrosis. Elevated endothelin levels are seen in individuals with hyperandrogenic states, such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and in trans men on long-term testosterone therapy.

- Oxidative Stress: By stimulating NADPH oxidase, testosterone increases reactive oxygen species, which in turn impair nitric oxide bioavailability, perpetuating vasoconstriction.

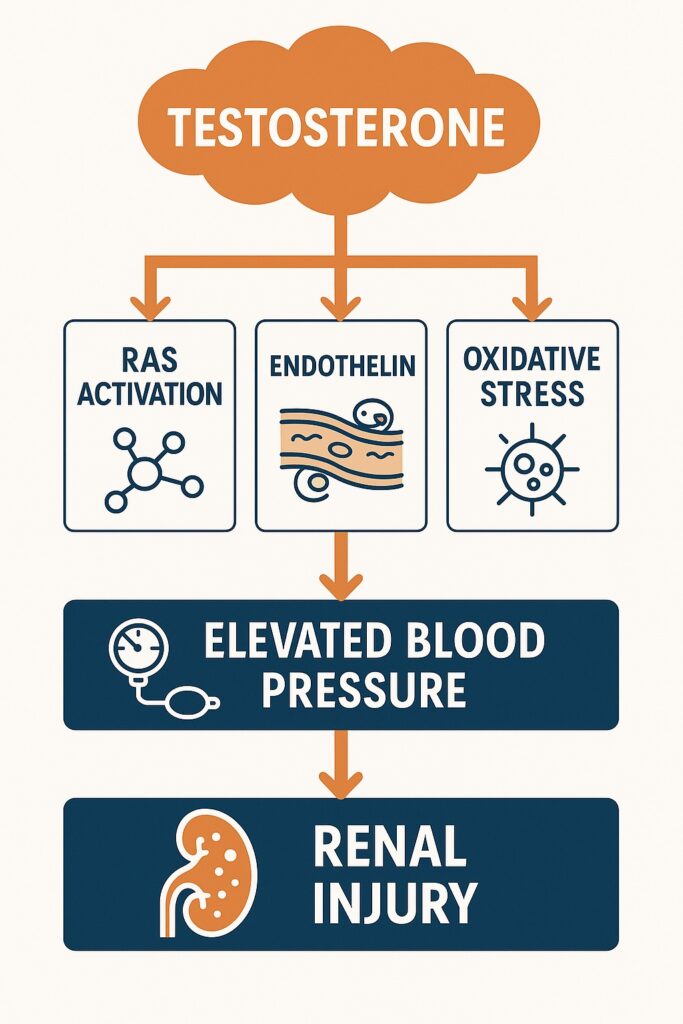

These interconnected pathways create a vicious cycle: testosterone → RAS activation → endothelin release → oxidative stress → hypertension and renal injury.

Testosterone, Oxidative Stress, and Inflammation

Oxidative stress and inflammation are common threads in both cardiovascular and renal aging. Men, even with declining testosterone, exhibit higher oxidative stress than women, as evidenced by increased F2-isoprostanes. After menopause, women catch up, in part because the antioxidant shield of estrogen is lost.

Testosterone supplementation can worsen this imbalance. Experimental studies demonstrate that testosterone enhances superoxide generation in mesangial cells and renal tissue, exacerbating vasoconstriction. It also stimulates cytokine release, upregulates NF-κB signaling, and promotes tubular apoptosis and fibrosis.

Thus, in the elderly, already vulnerable to oxidative and inflammatory stress, testosterone may add fuel to the fire, accelerating vascular and renal decline.

Clinical Implications for Men

For aging men, the clinical narrative is paradoxical. On the one hand, testosterone deficiency contributes to sarcopenia, osteoporosis, anemia, depression, and ED. On the other hand, supplementation risks amplifying hypertension, renal injury, and cardiovascular morbidity.

The safest candidates for testosterone therapy appear to be otherwise healthy hypogonadal men without significant cardiovascular or renal disease. In these individuals, the benefits—improved bone density, muscle mass, and sexual function—likely outweigh risks. But in men with CKD, uncontrolled hypertension, or heart disease, the therapy may act less like a rejuvenating tonic and more like a destabilizing accelerant.

Caution, therefore, is warranted. A blanket “anti-aging” prescription is not supported by science.

Clinical Implications for Women

The role of testosterone in postmenopausal women is equally complex. While supplementation can restore sexual desire and improve quality of life, it may also elevate blood pressure, worsen insulin resistance, and increase renal risk.

Unlike men, women naturally produce low levels of testosterone, and postmenopausal physiology often entails a relatively hyperandrogenic state. Adding exogenous testosterone in this context risks pushing physiology into supraphysiological exposure, particularly when dosing is not rigorously controlled.

Given that cardiovascular disease becomes the leading cause of death after menopause, testosterone supplementation should be prescribed with great caution. Long-term randomized trials are urgently needed to clarify risks versus benefits.

The Protective Decline Hypothesis

An intriguing perspective is that the natural decline in testosterone with age may be protective. Lower androgen levels might reduce the burden of hypertension and renal injury in elderly men, serving as a physiological adaptation to aging. By reintroducing testosterone through supplementation, clinicians may inadvertently reverse this protective decline, exposing patients to higher disease risk.

This concept parallels the lessons of estrogen replacement therapy in women: once heralded as universally protective, it later revealed cardiovascular hazards when applied indiscriminately. Testosterone therapy may be poised at a similar crossroads.

Conclusion

Testosterone supplementation is a double-edged sword in aging medicine. While capable of improving muscle strength, libido, and quality of life, it can simultaneously exacerbate hypertension, renal dysfunction, oxidative stress, and vascular injury. The balance between benefit and harm depends critically on patient selection, dose, and monitoring.

The clinical mandate is clear: caution, personalization, and rigorous evidence. Until large, long-term randomized trials are completed, testosterone should not be marketed as an anti-aging panacea. Instead, it should be reserved for carefully selected individuals with true hypogonadism, under close cardiovascular and renal surveillance.

Medicine’s task is not to deny patients the benefits of therapy but to weigh them soberly against potential harms. Testosterone, like all powerful hormones, demands respect for its biology and humility in its prescription.

FAQ

1. Is testosterone supplementation safe for older men with low levels?

It can be safe in carefully selected hypogonadal men without major cardiovascular or renal disease. However, risks include hypertension, fluid retention, and potential renal injury, requiring close monitoring.

2. Can women take testosterone after menopause to improve libido?

Yes, in select cases, but it must be prescribed cautiously. Women already enter a relatively hyperandrogenic state post-menopause, and excess testosterone may worsen cardiovascular or renal risk.

3. Why might nature reduce testosterone with age?

The decline may be protective, lowering vascular strain and slowing renal injury. Supplementing testosterone inappropriately might override this adaptation, increasing disease burden.