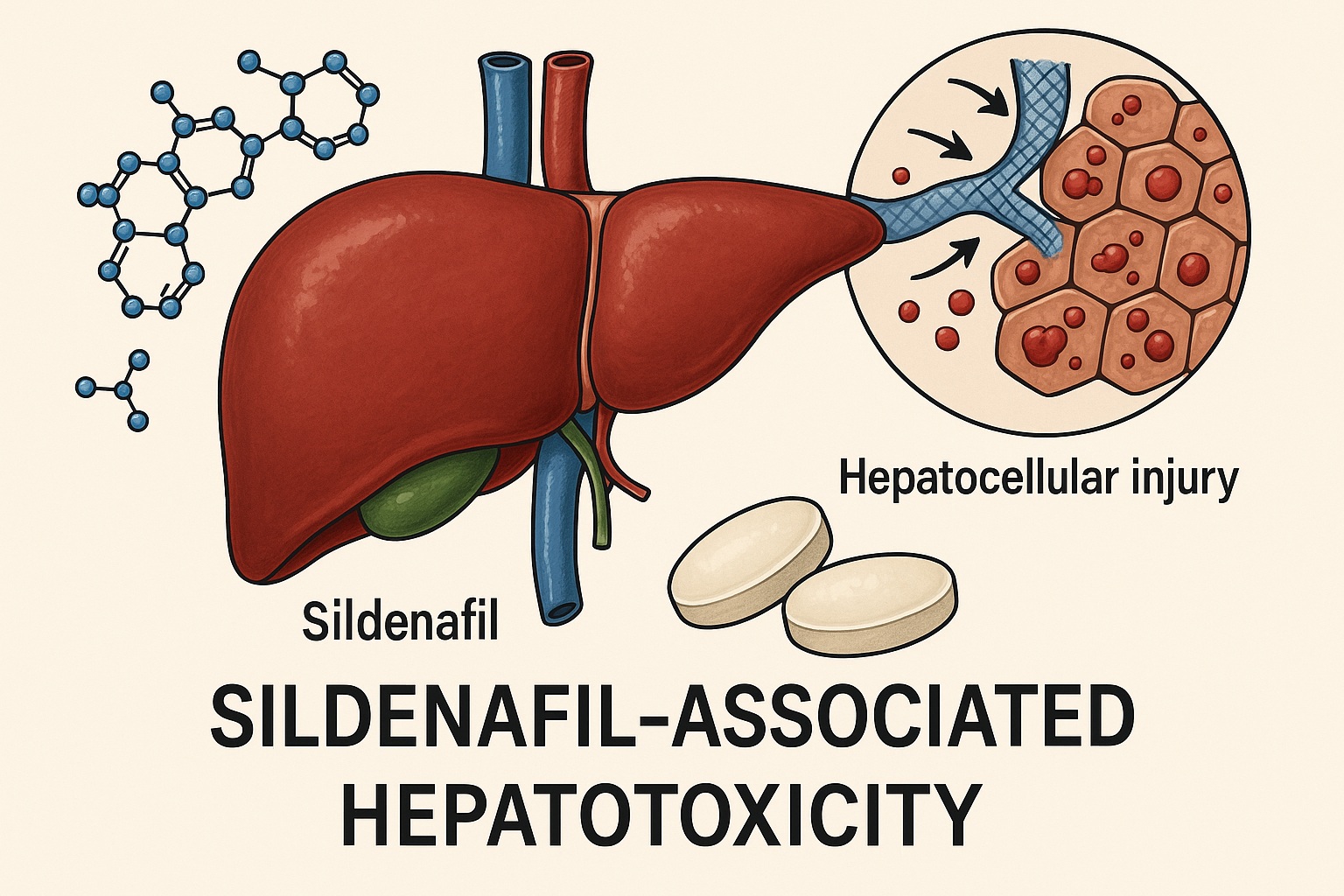

Since its approval in 1998, sildenafil citrate (Viagra®) has revolutionized the treatment of erectile dysfunction (ED) and expanded its therapeutic reach into pulmonary arterial hypertension and other vasculopathic conditions. With more than two decades of global use, sildenafil is widely considered safe when administered within its therapeutic range. Its well-known adverse effects—facial flushing, dyspepsia, headache, and transient visual disturbances—are generally benign. Yet, beneath this reassuring safety profile lies an underappreciated phenomenon: sildenafil-associated hepatotoxicity.

Although exceedingly rare, reported cases of liver injury linked to sildenafil raise questions about individual susceptibility, pharmacokinetic variability, and potential drug–drug interactions. Understanding this association is critical for clinicians who prescribe sildenafil or manage patients presenting with unexplained hepatic dysfunction.

Pharmacology and Hepatic Metabolism of Sildenafil: Why the Liver Matters

Sildenafil’s pharmacologic identity is defined by its selective inhibition of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5), the enzyme responsible for degrading cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). This action potentiates nitric oxide (NO)-mediated smooth muscle relaxation, leading to vasodilation in the corpus cavernosum, the pulmonary vasculature, and other vascular territories.

Following oral administration, sildenafil is rapidly absorbed, reaching peak plasma levels within one hour. Its terminal half-life ranges between three and six hours, and its oral bioavailability is approximately 40%. However, the pharmacokinetic story unfolds primarily in the liver, where sildenafil undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism via cytochrome P450 enzymes—CYP3A4 (major pathway) and CYP2C9 (minor).

The primary metabolite, N-desmethyl sildenafil (UK-103,320), retains about half the potency of the parent compound and circulates at 40–50% of its plasma concentration. Consequently, hepatic integrity is central to both the metabolism and clearance of sildenafil. In patients with hepatic congestion, cirrhosis, or elevated portal pressure, drug clearance diminishes, increasing systemic exposure and potential hepatocellular burden.

From a pharmacovigilance perspective, the liver’s dual role—as the metabolic gatekeeper and potential target of toxicity—makes it particularly vulnerable when drug clearance is compromised or when sildenafil is combined with other hepatically metabolized agents.

Mechanistic Insights: How Sildenafil May Induce Liver Injury

Despite scattered case reports and animal studies, the mechanism of sildenafil-induced hepatotoxicity remains speculative. Unlike drugs with well-defined hepatotoxic profiles (e.g., acetaminophen, amiodarone), sildenafil lacks a consistent biochemical or histological signature of liver damage. However, several pathophysiologic mechanisms have been proposed based on available evidence:

- Idiosyncratic immune-mediated injury: Many reported cases show features of cholestatic hepatitis with eosinophilic infiltration, suggesting an immune-allergic component rather than a direct cytotoxic effect.

- Ischemic or metabolic stress: Sildenafil’s vasodilatory properties may, paradoxically, induce transient hepatic hypoperfusion in susceptible individuals, especially when co-administered with antihypertensives or in those with cardiac insufficiency.

- CYP3A4-mediated reactive metabolites: As sildenafil is primarily metabolized by CYP3A4, its bioactivation may yield reactive intermediates capable of inducing oxidative stress or hepatocellular necrosis under certain metabolic conditions.

Animal studies further support these hypotheses. Histopathological findings in rats chronically exposed to sildenafil reveal dilatation of central veins, hepatocellular necrosis, bile duct hyperplasia, and inflammatory cell infiltration—hallmarks of toxic and ischemic injury combined.

While the causal pathway remains elusive, these observations underline the multifactorial nature of sildenafil-associated hepatotoxicity, likely involving both metabolic vulnerability and immunologic reactivity.

Clinical Case Evidence: Lessons from Reported Human Cases

The literature documents fewer than ten confirmed cases of sildenafil-associated hepatotoxicity, underscoring the rarity of this phenomenon. However, the diversity of presentations—from mild transient enzyme elevation to severe cholestatic hepatitis—demonstrates the need for heightened clinical awareness.

The first case, reported in 2003, involved a 65-year-old man who developed acute hepatitis one day after taking a single 50 mg dose of sildenafil. Laboratory results showed marked elevations in AST, ALT, GGT, and ALP, which normalized within four months after drug withdrawal. The hepatotoxic mechanism was presumed to be ischemic, potentially potentiated by concurrent calcium channel blocker therapy.

Subsequent reports have revealed both cytolytic and cholestatic injury patterns. A notable case in 2005 described a 56-year-old man with no prior hepatic disease who developed cholestatic hepatitis confirmed by biopsy—characterized by bile duct inflammation and eosinophilic infiltration—after two low-dose exposures to sildenafil. Viral, autoimmune, and metabolic causes were excluded. The patient’s hepatic enzymes normalized after several months of supportive care, and an immune-allergic mechanism was suspected.

Another case involved a 49-year-old diabetic man who experienced isolated hepatocellular injury without cholestasis after four weeks of daily sildenafil therapy. Withdrawal of the drug led to complete biochemical recovery within 20 days, again suggesting a dose-independent, idiosyncratic reaction.

A pattern emerges: sildenafil-induced liver injury often occurs after intermittent or short-term exposure, with delayed symptom onset, and resolves upon discontinuation. The absence of recurrence upon rechallenge—wisely avoided in all reported cases—supports a causal but unpredictable relationship.

The Hidden Threat: Adulterated “Herbal” Supplements Containing Sildenafil

In an era of online self-medication, clinicians must also contend with illicit or counterfeit products masquerading as “natural” aphrodisiacs. Laboratory investigations across Europe and Asia have identified therapeutic or supratherapeutic doses of sildenafil in more than three-quarters of herbal supplements marketed for sexual performance.

A particularly striking case involved a 65-year-old man hospitalized for acute hepatitis after consuming a Chinese “herbal” supplement called Tiger King. Chemical analysis revealed undeclared sildenafil (20–35 mg per dose). According to the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM), the link between sildenafil and hepatotoxicity was classified as “probable.” The patient’s symptoms resolved within a month of discontinuation.

These adulterated formulations not only obscure diagnosis but also amplify risk by delivering unpredictable sildenafil doses in individuals with pre-existing hepatic disease. Moreover, consumers often fail to disclose supplement use, complicating clinical evaluation. For clinicians, maintaining a high index of suspicion is essential when confronted with otherwise unexplained hepatitis in patients using over-the-counter or “herbal” sexual enhancers.

Diagnostic Considerations: Recognizing and Confirming Sildenafil-Induced Liver Injury

Diagnosing drug-induced liver injury (DILI) requires systematic exclusion of more common etiologies—viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, alcohol- or metabolic-associated liver disease, and biliary obstruction. Because sildenafil-associated hepatotoxicity is idiosyncratic, its diagnosis is one of probability rather than certainty.

The RUCAM score and Naranjo scale remain the most widely accepted tools for assessing causality. Both evaluate the temporal relationship between drug exposure and symptom onset, pattern of biochemical injury, response to drug withdrawal, and exclusion of alternative causes. In the published cases, sildenafil-related DILI generally met “possible” or “probable” criteria on both scales.

Clinically, sildenafil-induced hepatotoxicity can present with:

- Symptoms: malaise, jaundice, pruritus, right upper quadrant discomfort, and occasionally dark urine.

- Laboratory findings: elevation in AST, ALT, GGT, ALP, and bilirubin; the pattern may be hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed.

- Histopathology: portal and sinusoidal eosinophilic infiltration, bile stasis, mild necroinflammation, and hepatocanalicular injury.

Most patients recover fully within one to four months after discontinuation. Importantly, re-exposure should be strictly avoided, and patients should be counseled against using sildenafil-containing supplements or analogues.

Risk Factors: Who Is Most Vulnerable?

Although the rarity of cases limits firm conclusions, certain risk factors appear to predispose individuals to sildenafil-associated liver injury:

- Pre-existing hepatic impairment: Cirrhosis, steatosis, or hepatic congestion can reduce clearance and enhance exposure.

- Concomitant medications metabolized by CYP3A4, such as macrolide antibiotics, antifungal azoles, and calcium channel blockers, can raise plasma sildenafil concentrations.

- Advanced age may contribute to reduced hepatic metabolism and altered pharmacodynamics.

- Unregulated supplement use, particularly in those seeking sexual performance enhancement without medical supervision.

It is notable that in most cases, patients denied polypharmacy or alcohol abuse, suggesting idiosyncratic, host-specific susceptibility. Genetic polymorphisms in CYP3A4 or immunomodulatory pathways may play a yet-unexplored role in this variability.

Animal Data: Experimental Clues to Mechanistic Understanding

Animal models, though imperfect, provide valuable mechanistic insights. Multiple studies in adult Wistar rats treated with therapeutic to supratherapeutic doses of sildenafil over several weeks have shown histological evidence of hepatic congestion, necrosis, and inflammatory infiltration.

In one study, sildenafil exposure for six weeks induced dilatation of central veins and loss of hepatic architecture, with significantly elevated ALT, AST, and bilirubin levels. Even after drug withdrawal, recovery was incomplete, suggesting persistent cellular injury.

Another experiment found bile duct hyperplasia and hepatocyte nuclear distortion, consistent with cholestatic injury. Interestingly, these effects were dose-dependent, underscoring the importance of exposure level and duration. Such preclinical data strengthen the biological plausibility of sildenafil-induced hepatotoxicity and justify ongoing vigilance in human populations.

Clinical Vigilance and Management Strategies

Given the low incidence but potential severity of sildenafil-related liver injury, the clinician’s task is twofold: prevent occurrence and recognize early warning signs.

Before initiating sildenafil therapy, physicians should:

- Obtain a baseline liver function profile (AST, ALT, ALP, bilirubin), particularly in patients with known hepatic comorbidities.

- Review concomitant medications for CYP3A4 interactions.

- Counsel patients on avoiding over-the-counter or herbal sexual enhancers.

If hepatic symptoms or enzyme elevations occur during sildenafil use, prompt discontinuation is indicated. Supportive management—hydration, monitoring of liver enzymes, and avoidance of hepatotoxic agents—usually suffices.

In severe or cholestatic cases, short courses of ursodeoxycholic acid or corticosteroids have been used empirically, though evidence is anecdotal. Rechallenge with sildenafil or related PDE5 inhibitors (tadalafil, vardenafil) should be strictly avoided unless the benefits clearly outweigh the risks, and even then, under specialist supervision.

Conclusion: A Rare but Real Adverse Effect Worth Remembering

Sildenafil-associated hepatotoxicity remains a rare but clinically relevant phenomenon. While most patients tolerate sildenafil without incident, clinicians must remain alert to unexplained liver enzyme abnormalities, particularly in individuals taking multiple drugs metabolized by CYP3A4, those with pre-existing hepatic disease, or those using unregulated “herbal” supplements.

The existing literature—though limited to a handful of well-documented cases—underscores a pattern of reversible, idiosyncratic injury, often cholestatic in nature and resolving after drug withdrawal. Given sildenafil’s extensive hepatic metabolism, routine vigilance rather than alarmism is the appropriate stance.

For physicians, the lesson is clear: sildenafil is safe for most, but not all. A good sexual life begins with a healthy liver—and sometimes, that means asking the extra question about what patients take, and why.

FAQ: Sildenafil and Liver Safety

1. How common is sildenafil-associated hepatotoxicity?

Extremely rare. Fewer than ten confirmed human cases have been reported worldwide, despite millions of prescriptions. However, underreporting and supplement adulteration may obscure the true incidence.

2. What should physicians do if a patient on sildenafil presents with elevated liver enzymes?

Immediately discontinue the drug, rule out alternative causes, and monitor liver function tests. Most cases resolve spontaneously within weeks to months without the need for specific therapy.

3. Is sildenafil safe in patients with pre-existing liver disease?

Caution is advised. Lower starting doses are recommended, and regular monitoring of liver enzymes is prudent. Avoid use in patients with severe hepatic impairment or active hepatitis.