Introduction

Surgery on the liver has always been one of the more daring feats of modern medicine. The liver is large, richly vascularized, and unforgiving of surgical miscalculations. Hepatectomy—the removal of a portion of the liver—remains central to treating cancers such as hepatocellular carcinoma and colorectal liver metastases. Yet despite advances in surgical technique, anesthesia, and perioperative care, complications remain a stubborn companion. Among the most feared is ischemia–reperfusion injury (IRI), an insult that occurs when blood flow to the liver is temporarily interrupted during surgery and then restored.

This injury, paradoxically triggered by the very act of restoring oxygen, can ignite cascades of oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. The consequences range from transient liver enzyme spikes to frank liver failure. For patients already compromised by cirrhosis, steatosis, or chemotherapy-induced damage, the stakes are even higher.

Against this backdrop, researchers have been searching for strategies that might cushion the liver against the storm of reperfusion. Some have looked to ischemic preconditioning, others to antioxidants or pharmacologic agents. Now, in an intriguing twist, a medication better known for treating erectile dysfunction—sildenafil citrate—is stepping into the operating theater as a potential liver protector.

Why Sildenafil? A Brief Pharmacologic Detour

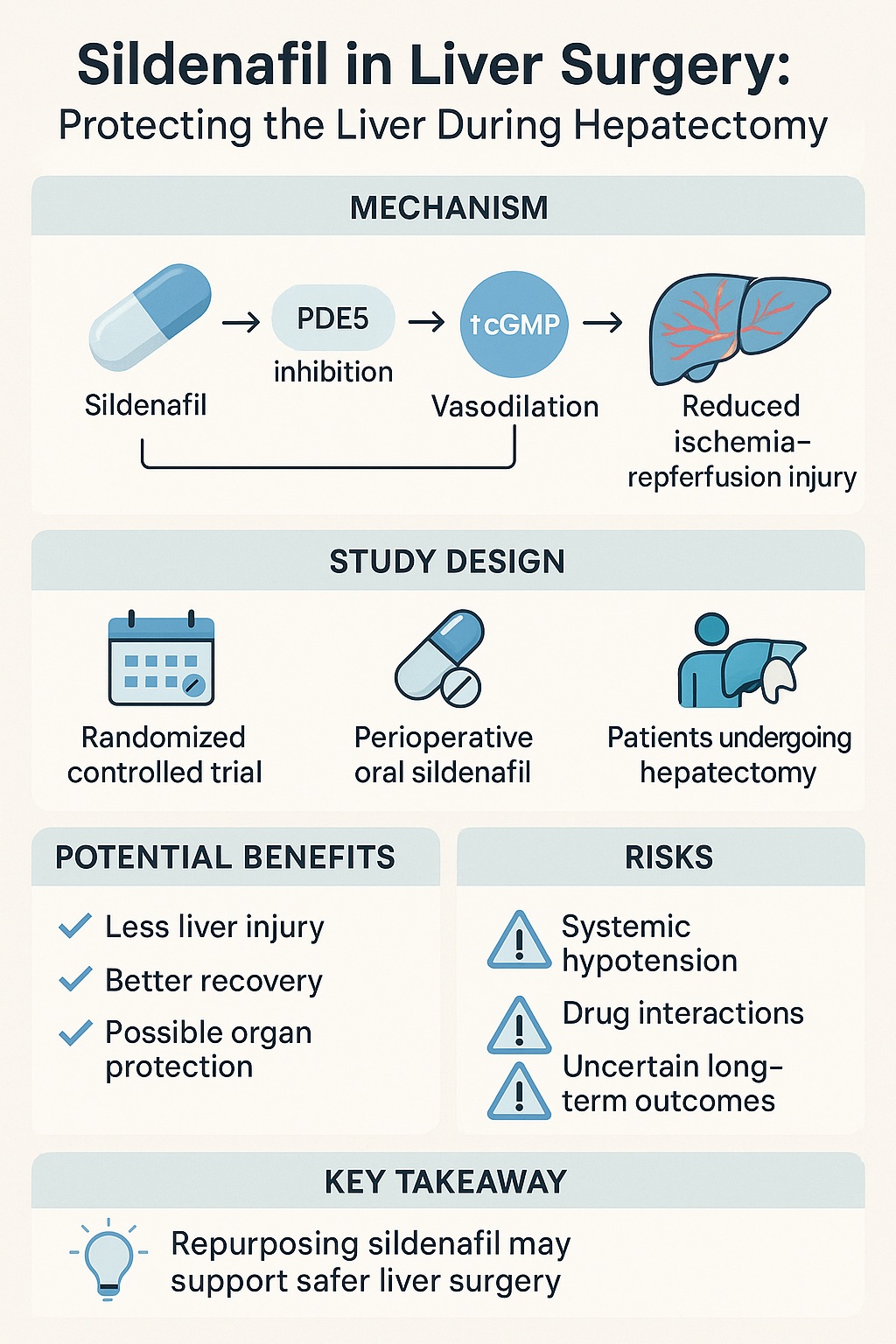

Sildenafil belongs to the family of phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5) inhibitors. By blocking PDE5, it prevents the breakdown of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), thereby enhancing nitric oxide–mediated vasodilation. In simple terms, it makes blood vessels relax and widen. That mechanism explains its success in treating erectile dysfunction and pulmonary arterial hypertension.

But PDE5 inhibition is not limited to the penile vasculature or the pulmonary circulation. The liver, too, is a vascular organ dependent on tightly regulated blood flow. Within hepatic sinusoids, endothelial cells and stellate cells express nitric oxide synthase, and the NO–cGMP pathway is a key determinant of intrahepatic resistance. Disturbances in this system are implicated in portal hypertension and liver injury.

Animal studies have suggested that sildenafil may do more than dilate vessels. It may:

- Reduce oxidative stress during reperfusion.

- Improve microcirculatory flow within the liver parenchyma.

- Dampen inflammatory cascades by modulating endothelial signaling.

Such findings raise the tantalizing possibility that a single oral tablet, given before surgery, could render the liver more resilient against IRI.

The Problem of Ischemia–Reperfusion in Hepatectomy

Hepatectomy often requires temporary clamping of the hepatic inflow, commonly known as the Pringle maneuver, to minimize bleeding. While effective for hemostasis, this maneuver subjects the liver to warm ischemia. When clamps are released and reperfusion begins, the sudden flood of oxygenated blood paradoxically causes more damage than the ischemia itself.

The pathophysiology of hepatic IRI involves:

- Oxidative stress: Reactive oxygen species accumulate rapidly upon reperfusion.

- Endothelial dysfunction: The delicate lining of hepatic sinusoids swells, obstructing microcirculatory flow.

- Inflammatory activation: Kupffer cells and neutrophils release cytokines that propagate tissue damage.

- Mitochondrial injury: Energy failure ensues, further impairing hepatocyte survival.

Clinically, this translates to postoperative liver dysfunction, elevated transaminases, impaired regeneration, and in severe cases, acute liver failure. Preventing or mitigating IRI remains a holy grail in hepatobiliary surgery.

The Clinical Trial: Sildenafil Enters the Stage

The study in question is a prospective randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate whether perioperative sildenafil citrate can reduce ischemia–reperfusion injury in patients undergoing hepatectomy. Conducted in a high-volume surgical center, it represents one of the first rigorous attempts to translate experimental findings into human liver surgery.

Design in Brief

- Population: Adult patients scheduled for elective hepatectomy, with adequate baseline liver function.

- Intervention: A single oral dose of sildenafil citrate administered preoperatively.

- Control: Standard perioperative management without sildenafil (placebo-controlled).

- Endpoints: Primary outcomes include markers of hepatic injury (ALT, AST, bilirubin), microcirculatory parameters, and perioperative hemodynamics. Secondary outcomes cover complication rates, length of stay, and liver regeneration indices.

The trial is carefully structured to balance safety and innovation. Given sildenafil’s established safety profile in other indications, the barrier to clinical testing is lower than for entirely new agents.

Early Clues from Preclinical Evidence

Before leaping to human trials, researchers accumulated preclinical evidence pointing toward sildenafil’s hepatoprotective potential. In rodent models of hepatic ischemia–reperfusion, sildenafil pretreatment reduced histologic evidence of necrosis, improved microcirculatory flow, and enhanced survival. Biochemically, treated livers exhibited lower malondialdehyde levels (a marker of oxidative stress) and higher superoxide dismutase activity (an antioxidant defense).

Interestingly, some studies also suggested that sildenafil might augment liver regeneration, a crucial process after partial hepatectomy. The proposed mechanism involves enhanced endothelial nitric oxide signaling, leading to better perfusion of regenerating hepatocytes. Though speculative, such a dual benefit—protection plus regeneration—would make sildenafil an unusually versatile perioperative adjunct.

Still, animal models have misled clinicians before. The transition from rodent liver lobes to complex human surgeries is fraught with uncertainty. Hence, a randomized controlled trial is not just desirable but essential.

Hemodynamic Considerations: A Double-Edged Sword

Any discussion of sildenafil in the operating room must address the elephant in the room: systemic vasodilation. In theory, sildenafil’s relaxation of systemic arteries could lower blood pressure, complicating anesthetic management during major surgery. Anesthesiologists are understandably cautious about introducing potential hypotensive agents into already complex hemodynamic environments.

The hope, however, rests on sildenafil’s relative pulmonary and hepatic selectivity. By preferentially acting on PDE5-rich vascular beds, it may spare systemic pressures while still enhancing hepatic perfusion. Clinical trials must carefully monitor intraoperative hemodynamics to confirm this balance.

A successful outcome would position sildenafil as a rare agent that both protects the liver and maintains systemic stability. A less favorable result—widespread hypotension—would consign it to the growing graveyard of perioperative pharmacologic disappointments.

Potential Benefits Beyond the Liver

Though the trial’s primary focus is hepatic protection, sildenafil’s pharmacology suggests ancillary benefits. For example, many hepatectomy patients exhibit features of pulmonary hypertension, especially those with underlying cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Sildenafil’s ability to lower pulmonary arterial pressures without systemic collapse, demonstrated in cardiac surgical settings, could prove doubly advantageous here.

Furthermore, improved microcirculation may benefit other vulnerable organs, such as the kidneys, which often suffer collateral ischemic insults during major abdominal surgery. Whether such protective spillover occurs remains to be seen, but the possibility broadens sildenafil’s appeal as a perioperative agent.

Risks and Uncertainties

Every potential innovation carries risks. For sildenafil in hepatectomy, concerns include:

- Systemic hypotension: Even selective vasodilation can be unpredictable under anesthesia.

- Drug interactions: Nitrates, commonly used in cardiac patients, are contraindicated with sildenafil due to severe hypotension risk.

- Variable pharmacokinetics: Liver disease itself alters drug metabolism, potentially exaggerating or blunting sildenafil’s effects.

- Unclear long-term outcomes: Even if perioperative markers improve, whether this translates into meaningful clinical benefits—lower complication rates, faster recovery, improved survival—remains uncertain.

These uncertainties highlight why a carefully designed randomized controlled trial is essential before wider adoption.

Educational Perspective: Why This Matters

For a broader audience, one might ask: why does this matter? Isn’t liver surgery already quite safe in modern centers? While true, safety is relative. Major hepatectomy carries reported morbidity rates of 20–40% and mortality rates of 1–5%, depending on patient comorbidities and surgical complexity. Any intervention that reduces complications, shortens hospital stays, or improves liver recovery has real-world value.

Moreover, the concept of drug repurposing resonates here. Sildenafil, a familiar medication with a well-established safety profile, could be leveraged for an entirely new perioperative purpose. This approach is cost-effective, practical, and potentially transformative. It exemplifies how modern medicine increasingly seeks to adapt existing molecules to new challenges rather than endlessly inventing de novo compounds.

Broader Implications: The Future of Perioperative Pharmacology

The sildenafil trial reflects a broader shift in perioperative medicine: the search for organ-protective pharmacology. Surgeons and anesthesiologists increasingly recognize that the success of complex operations hinges not only on technical skill but also on mitigating collateral damage. From beta-blockers in cardiac surgery to N-acetylcysteine in kidney protection, the idea of “pharmacologic conditioning” is gaining traction.

If sildenafil proves effective in hepatectomy, similar trials might explore its use in liver transplantation, trauma surgery, or even non-hepatic procedures where ischemia–reperfusion plays a role. Beyond surgery, the results may enrich our understanding of NO–cGMP signaling in organ protection more broadly.

Conclusion

The idea of giving sildenafil to a patient about to undergo liver surgery may sound unconventional, even whimsical. Yet beneath the surprise lies a solid pharmacologic rationale and a carefully designed clinical trial. By enhancing hepatic microcirculation, reducing oxidative stress, and stabilizing endothelial signaling, sildenafil could emerge as a valuable tool against ischemia–reperfusion injury in hepatectomy.

Caution remains appropriate. Only rigorous human data will reveal whether the theoretical and animal-model benefits translate into genuine clinical gains. But if successful, this trial may mark the beginning of a new chapter in perioperative medicine—where a drug best known for one sphere of life becomes a quiet guardian in another, protecting the liver when it is most vulnerable.

FAQ

1. Why would doctors give sildenafil to liver surgery patients?

Because sildenafil may protect the liver against ischemia–reperfusion injury, a common problem in hepatectomy. By improving microcirculation and reducing oxidative stress, it could help the liver recover more smoothly after surgery.

2. Is it safe to use sildenafil during major surgery?

So far, evidence suggests sildenafil is generally safe, but concerns remain about systemic hypotension and drug interactions. That is why randomized controlled trials are being conducted before routine use.

3. Could sildenafil also help in other surgeries or conditions?

Possibly. Its protective effects may extend to transplantation, trauma surgery, or other ischemic conditions. More research will be needed to confirm these broader applications.