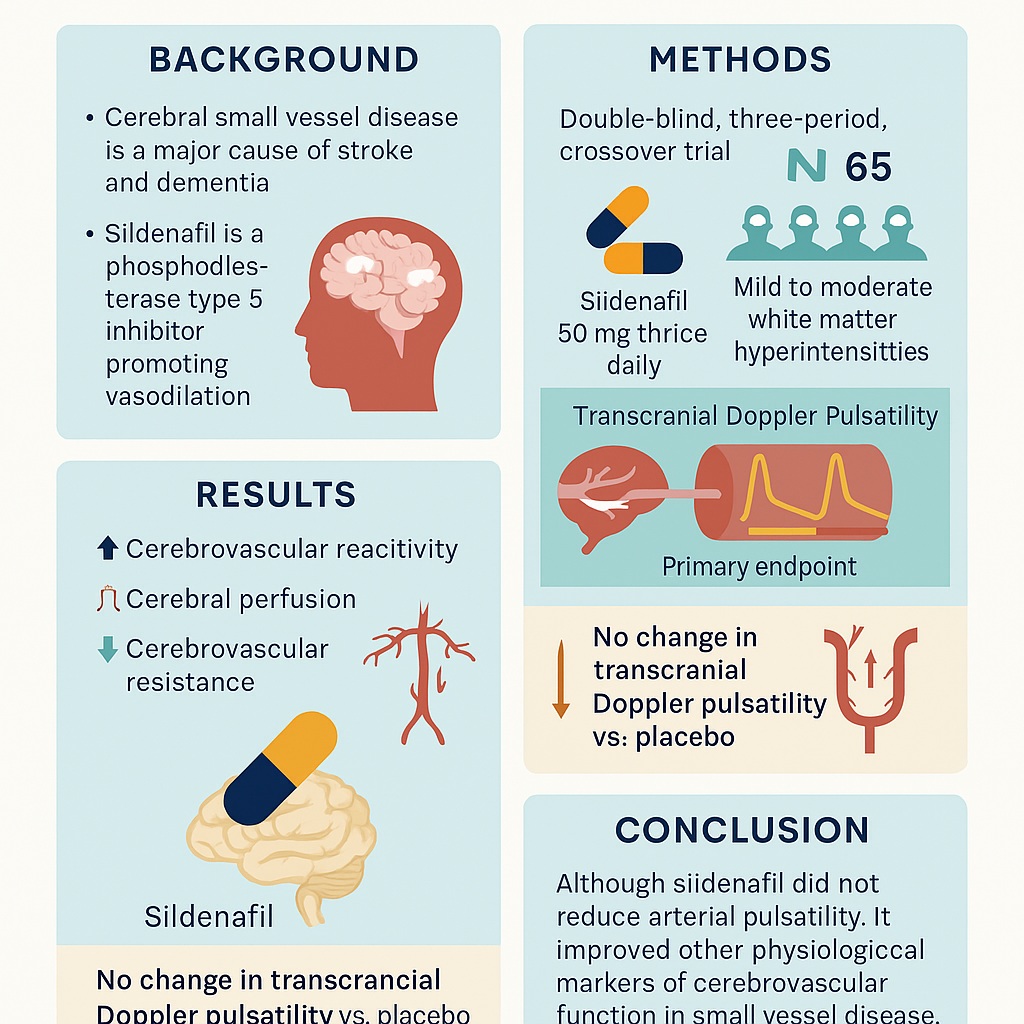

Cerebral small vessel disease (cSVD) is one of the silent culprits of modern neurology. Often invisible until it manifests as stroke, cognitive decline, or dementia, cSVD has proven remarkably resistant to targeted therapies. For decades, clinicians have relied on controlling risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and cholesterol while offering only symptomatic support once neurological damage becomes evident. Against this sobering backdrop, the Oxford Haemodynamic Adaptation to Reduce Pulsatility (OxHARP) trial has emerged as a landmark attempt to repurpose an unlikely pharmacological ally: sildenafil. Known popularly as Viagra and clinically as a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor (PDE5i), sildenafil is a vasodilator with well-established safety. But could this familiar drug alter the pathophysiological dynamics of the brain’s smallest blood vessels?

The OxHARP trial provides a rigorous first attempt to answer that question. Its findings, though nuanced, carry important implications for neurology, cardiology, and geriatric medicine. This article will explore the scientific rationale, methodology, outcomes, and broader meaning of the trial, while placing the results in the context of decades of work on vascular brain disease. The reader is invited to move beyond the clichés of “blue pills” and instead consider sildenafil as a potential neuroprotective therapy with serious scientific credibility.

Understanding Cerebral Small Vessel Disease

Cerebral small vessel disease refers to chronic structural and functional changes in the brain’s small arteries, arterioles, venules, and capillaries. On MRI scans, it manifests as white matter hyperintensities (WMH), lacunar infarcts, cerebral microbleeds, and dilated perivascular spaces. Clinically, it contributes to nearly a third of ischemic strokes, most intracerebral hemorrhages, and up to 40% of dementias. In epidemiological terms, this makes cSVD one of the greatest contributors to neurological morbidity worldwide.

The pathophysiology of cSVD is complex. Chronic hypertension stiffens arteries, leading to increased pulsatile stress on cerebral microcirculation. Endothelial dysfunction allows disruption of the blood–brain barrier, encouraging leakage of plasma proteins and toxic metabolites. Hypoperfusion of white matter results in gradual loss of axons and oligodendrocytes. Together, these processes create a “perfect storm” for progressive vascular cognitive impairment. Yet, despite the enormous burden, no drug to date has been specifically approved for cSVD.

The challenge lies partly in measuring disease activity. Unlike atherosclerosis, which can be tracked by angiography, cSVD plays out on a microscopic scale. Researchers rely on physiological surrogates such as pulsatility index on transcranial Doppler, cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) to CO₂, and perfusion imaging. Improvements in these markers are taken as signs that a therapy may translate into clinical benefit. It is precisely this physiological landscape that OxHARP set out to explore.

The Case for Endothelial-Targeted Therapies

The endothelium is not just a passive barrier; it is a dynamic organ controlling vascular tone, coagulation, and permeability. Dysfunction of this layer is a central feature of cSVD. Drugs that target endothelial function are therefore logical candidates for intervention. Two such therapies—isosorbide mononitrate (ISMN) and cilostazol—have shown modest improvements in small trials. ISMN, a nitric oxide donor, enhanced CVR in the LACI-1 pilot and hinted at cognitive benefits in LACI-2. Cilostazol, a phosphodiesterase-3 inhibitor, reduced pulsatility and recurrent stroke risk in Asian populations.

Sildenafil, meanwhile, enhances the nitric oxide–cGMP pathway by inhibiting PDE5, thereby sustaining vasodilation in smooth muscle. Its efficacy is well documented in erectile dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, and Raynaud’s phenomenon. Observational studies have even linked sildenafil use with reduced dementia incidence. Animal studies support amyloid-independent neuroprotection. With this background, sildenafil was a plausible, safe, and widely available drug to test in the context of cSVD.

The OxHARP Trial: Design and Rationale

The Oxford Haemodynamic Adaptation to Reduce Pulsatility (OxHARP) trial was a phase II, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, three-way crossover study conducted at the University of Oxford. Its design was methodologically rigorous, combining clinical neurology, advanced imaging, and statistical sophistication.

Seventy-five participants were recruited, all with prior lacunar stroke or transient ischemic attack and evidence of mild to moderate WMH. The median age was 70, with nearly 80% being male. Participants sequentially received three treatments—placebo, sildenafil (50 mg three times daily), and cilostazol (100 mg twice daily)—for three weeks each, separated by washout periods. This crossover ensured each individual acted as his or her own control, thereby enhancing statistical power.

The primary endpoint was cerebral pulsatility index measured by transcranial Doppler, chosen because pulsatility reflects arterial stiffness and correlates strongly with cSVD progression. Secondary outcomes included cerebrovascular reactivity (to CO₂ challenges), cerebral perfusion assessed by arterial spin labeling MRI, and cerebrovascular resistance. The trial also evaluated safety and tolerability, given that these drugs can cause headaches, diarrhea, and other vascular side effects.

What Did the Trial Show?

The results of OxHARP were both encouraging and humbling. On the primary endpoint, sildenafil failed to significantly reduce pulsatility compared with placebo. In other words, the hypothesized dampening of systolic-diastolic velocity swings did not materialize over the three-week treatment window. From a strict statistical perspective, this meant the trial did not meet its primary goal.

However, the secondary outcomes told a more compelling story. Sildenafil improved cerebrovascular reactivity on both ultrasound and MRI, increased cerebral blood flow velocities, and enhanced perfusion in both white matter hyperintensities and normal-appearing tissue. Importantly, it reduced cerebrovascular resistance, consistent with effective vasodilation at the microvascular level. These changes occurred without serious adverse events and with tolerability comparable to placebo. The main side effect was mild headache, predictable given vasodilation.

Cilostazol, used as a comparator, showed non-inferior effects but carried a higher burden of diarrhea, consistent with prior studies. Notably, sildenafil produced measurable physiological benefits without sacrificing tolerability, an advantage that matters when considering long-term therapy for elderly patients.

Pulsatility: A Moving Target?

Why did sildenafil fail to reduce pulsatility despite clear evidence of vasodilation and improved reactivity? The answer lies in the physiology of pulsatility itself. Pulsatility index is influenced not only by distal vascular resistance but also by central aortic stiffness, wave reflections, and heart rate. In older patients with entrenched arterial stiffening, a few weeks of vasodilation may be insufficient to alter the central waveform. Indeed, the OxHARP investigators speculated that pulsatility in their population reflected systemic vascular mechanics rather than local microvascular tone.

This finding underscores a key lesson: pulsatility may not always be the best short-term surrogate for therapeutic effect. Improvements in cerebrovascular reactivity and perfusion may prove more sensitive and clinically relevant markers. As such, the trial shifts the emphasis toward dynamic measures of endothelial function rather than static indices of stiffness.

Implications for Cognitive Health

The link between cerebral perfusion and cognition is increasingly recognized. Hypoperfusion of white matter contributes to executive dysfunction, slowed processing, and eventual dementia. If sildenafil can restore perfusion and enhance vascular responsiveness, it might slow or prevent cognitive decline in cSVD. Observational data hint in this direction: large population studies have found associations between PDE5i use and lower dementia risk.

Of course, association is not causation. The OxHARP trial cannot claim cognitive benefit, since its duration was only three weeks and it did not include cognitive outcomes. Yet the improved hemodynamics provide a strong rationale for longer trials that track cognitive trajectories over months or years. In an era where Alzheimer’s disease research has focused heavily on amyloid and tau—with disappointing therapeutic returns—vascular interventions such as sildenafil deserve serious attention.

Safety and Tolerability: Not Just a Footnote

Long-term therapy for cSVD must be safe and tolerable, given the chronic nature of the disease and the advanced age of patients. Here, sildenafil has several advantages. It has been prescribed to millions worldwide, with a well-characterized safety profile. In OxHARP, headaches were the most common side effect but were generally mild. A small proportion of men reported increased tumescence, which might raise blinding concerns but is hardly a catastrophic adverse event. No serious cardiovascular complications were reported.

By contrast, cilostazol caused diarrhea in nearly a third of participants, some of it moderate to severe. This side effect has long limited its uptake outside Asia. Thus, even if sildenafil and cilostazol were physiologically equivalent, sildenafil’s tolerability would confer a practical advantage.

Redefining Clinical Trials in Small Vessel Disease

Beyond the drug itself, OxHARP is notable for its paradigm of physiological testing. By combining transcranial ultrasound and advanced MRI, the investigators could map drug effects across multiple vascular domains. This multimodal approach sets a new benchmark for phase II trials in cSVD. Rather than waiting years for clinical outcomes like stroke or dementia, researchers can use validated intermediate markers to rapidly screen candidate drugs. If successful, such methods may accelerate the pipeline of therapies for a condition that has languished for decades without specific treatment.

Limitations and Future Directions

No trial is without caveats, and OxHARP is no exception. Its treatment periods were short—only three weeks per drug—so longer-term adaptations may not have emerged. The population was relatively homogeneous (mostly older white men), limiting generalizability to women and other ethnic groups. The study did not measure blood–brain barrier permeability, another crucial aspect of cSVD. And while physiological improvements were clear, clinical outcomes such as stroke recurrence or cognitive decline remain untested.

Still, the trial lays the groundwork for future phase III studies. Logical next steps include:

- Testing sildenafil over 12–24 months with cognitive and functional endpoints.

- Expanding recruitment to more diverse populations.

- Incorporating fluid biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction.

- Comparing sildenafil with other endothelial-targeted drugs in head-to-head designs.

Such work will determine whether sildenafil is merely a physiological curiosity or a genuine neuroprotective therapy.

Broader Reflections: The Irony of Repurposing

There is a touch of irony in all this. A drug initially developed for angina, which became a global symbol of sexual health, now finds itself investigated as a protector of aging brains. This trajectory exemplifies the power of drug repurposing, where existing medications with known safety can be redirected to new indications. Repurposing is efficient, cost-effective, and often clinically impactful. If sildenafil were ultimately proven to reduce stroke or dementia risk, it would mark one of the most surprising second acts in pharmacological history.

Conclusion

The OxHARP trial did not provide a dramatic breakthrough—pulsatility was unchanged—but it did offer something arguably more valuable: a robust signal that sildenafil improves cerebrovascular reactivity, perfusion, and resistance in patients with small vessel disease. These changes, achieved safely and with good tolerability, make sildenafil a compelling candidate for larger, longer trials aimed at preventing stroke and cognitive decline.

In short, sildenafil may not yet be the “blue pill for the brain,” but it has certainly earned its place at the table of serious contenders in vascular neurology. For a disease that contributes to nearly half of all dementias and has lacked specific therapy, this represents genuine progress.

FAQ

1. Does sildenafil reduce the risk of stroke or dementia in patients with small vessel disease?

Not yet proven. The OxHARP trial showed physiological improvements but did not measure long-term clinical outcomes. Larger, longer trials are needed to confirm whether these translate into reduced risk.

2. How does sildenafil compare with cilostazol for treating small vessel disease?

In OxHARP, sildenafil was non-inferior to cilostazol in physiological effects and was better tolerated, particularly because cilostazol caused more diarrhea. Sildenafil also improved cerebrovascular reactivity more consistently.

3. Is it safe for older patients with vascular disease to take sildenafil?

Yes, in general. Sildenafil has an excellent safety profile, even in elderly populations, provided contraindications such as concurrent nitrate therapy are avoided. In OxHARP, the main side effect was mild headache, and no serious adverse events occurred.