Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) remains one of the most devastating neurological events, not only because of its obvious motor and sensory consequences but also because of the silent, often unspoken burden of sexual dysfunction. For many patients, the restoration of ambulation or bladder function ranks below the yearning for a return to sexual intimacy. Indeed, surveys repeatedly reveal that sexual health is among the highest priorities for men and women living with SCI. The irony is striking: while advances in rehabilitation medicine have transformed survival and mobility, sexual health frequently lags behind in both research and practice.

Sexual dysfunction in SCI is complex, rooted in the anatomical disruption of reflex arcs, impairment of psychogenic responses, hormonal imbalances, and the psychosocial turmoil that follows injury. It is not simply about erectile or vaginal function but involves fertility, orgasmic capacity, satisfaction, and the ability to engage in intimate partnerships. Physicians too often shy away from these discussions, leaving patients isolated and misinformed. This silence perpetuates myths, delays intervention, and diminishes quality of life.

The challenge, therefore, is not just medical but cultural. A comprehensive approach to sexual disorders after SCI must integrate physiology with psychology, pharmacology with counseling, and rehabilitation with intimacy. This article explores the mechanisms underlying sexual dysfunction in SCI, the available therapeutic interventions, and the evolving strategies aimed at restoring not only function but also confidence and connection.

Neurophysiology of Sexual Function and SCI

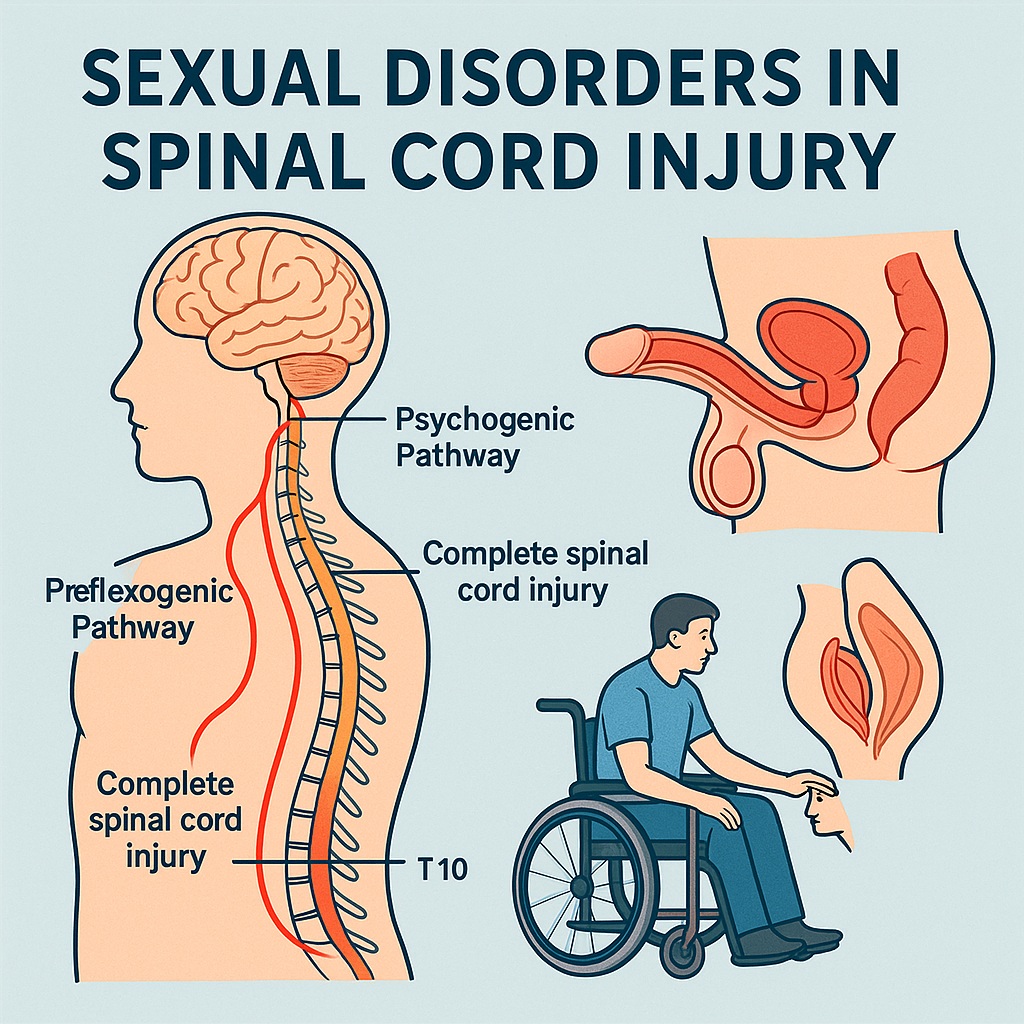

Sexual function is orchestrated through an intricate interplay between the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and endocrine system. The spinal cord serves as a relay station, channeling descending signals from higher centers and integrating reflex arcs that mediate genital responses.

Two principal pathways govern erection in men: reflexogenic erection, triggered by direct genital stimulation and mediated through the sacral spinal cord (S2–S4), and psychogenic erection, elicited by erotic thoughts or audiovisual stimuli via thoracolumbar outflow (T11–L2). Ejaculation involves yet another coordinated sequence, integrating sympathetic, parasympathetic, and somatic components. In women, lubrication, engorgement, and orgasm rely on homologous spinal mechanisms.

SCI disrupts these pathways according to lesion level and completeness. High cervical or thoracic injuries often spare reflexogenic erections but abolish psychogenic ones, while sacral lesions abolish reflexogenic capacity but may leave psychogenic responses intact. Similarly, ejaculation is frequently impaired, with complete lesions often preventing emission or expulsion. In women, vaginal lubrication and orgasmic potential may be reduced, though fertility is usually preserved. The variability underscores why no two patients present identically—and why individualized assessment is essential.

Psychological and Social Dimensions

The physiological insult of SCI is only half the story. Sexuality is as much psychological and relational as it is neurogenic. The trauma of injury often shatters self-image, erodes confidence, and introduces depression or anxiety. Cultural taboos may compound silence around sexual topics, while strained relationships test both partners.

For men, the inability to perform penetrative intercourse often feels like a direct attack on masculinity. Women, though often fertile, may fear pregnancy complications or struggle with body image. Partners may harbor anxieties about causing harm during sexual activity, further distancing intimacy. These psychological barriers can sometimes outweigh the neurogenic deficits, leading to avoidance of sexual contact altogether.

Addressing these dimensions requires more than medication. Counseling, sex therapy, and open communication with partners are critical. Yet, many rehabilitation programs fail to integrate sexual health into their curricula. Physicians may avoid the subject due to discomfort or lack of training, while patients hesitate to ask, assuming nothing can be done. Breaking this silence is the first therapeutic step.

Erectile Dysfunction After SCI

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is the most extensively studied sexual complication in men with SCI. Estimates suggest that up to 80% of male SCI patients experience significant erectile difficulty. The pathophysiology reflects disruption of neural pathways combined with impaired penile hemodynamics.

Treatment begins with oral PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil, tadalafil, or vardenafil. These agents enhance nitric oxide–cGMP signaling, promoting smooth muscle relaxation in the corpus cavernosum. Success rates in SCI are encouraging, with up to 80% of patients achieving satisfactory erections. However, outcomes depend on lesion completeness, with better responses in incomplete injuries.

For non-responders, intracavernosal injection therapy with prostaglandin E1, or combination regimens (trimix: papaverine, phentolamine, prostaglandin), provide robust results. Vacuum erection devices (VEDs) offer a mechanical alternative, though they may be cumbersome. For refractory cases, penile prosthesis implantation provides definitive though invasive correction. Importantly, therapy should always be paired with counseling, as erection quality does not guarantee satisfaction without emotional readiness.

Ejaculatory and Orgasmic Disorders

Ejaculatory dysfunction is particularly prevalent in SCI. While erections may be pharmacologically restored, the ability to ejaculate is often lost. Emission requires sympathetic outflow from T11–L2, while expulsion relies on somatic innervation from S2–S4. Depending on lesion site, one or both processes may fail.

Several strategies exist. Penile vibratory stimulation (PVS) is the first-line option for men with lesions above T10, inducing ejaculation in a majority of cases. Electroejaculation (EEJ), performed under anesthesia, provides reliable results across lesion levels and is widely used in fertility clinics. Pharmacological agents such as midodrine, ephedrine, or prostaglandins can sometimes facilitate emission but are less consistent.

Orgasmic sensation is more complex. Some men and women with SCI report preserved orgasm despite absent genital sensation, suggesting central reorganization. Others lose orgasm entirely, compounding distress. Here, psychosexual counseling and guided experimentation play key roles, encouraging couples to explore erogenous zones beyond the genitals.

Female Sexual Dysfunction in SCI

Compared with men, female sexual health after SCI has been under-researched, a disparity that reflects longstanding gender bias in medicine. Yet women with SCI face profound challenges.

Vaginal lubrication, mediated by parasympathetic outflow, is often impaired, leading to dryness and dyspareunia. PDE5 inhibitors and topical lubricants have been tried with variable success. Genital engorgement and sensitivity may be reduced, though orgasm is sometimes preserved, particularly in incomplete lesions.

Fertility is generally intact, but pregnancy carries additional risks: urinary tract infections, autonomic dysreflexia during labor, and thromboembolic events. Obstetricians must coordinate closely with rehabilitation specialists. Despite these hurdles, many women with SCI conceive and deliver safely. The key lies in informed counseling and proactive management, rather than presumption of infertility.

Psychologically, women face the same struggles as men: altered body image, fear of rejection, and diminished self-esteem. Partner education and couple-based interventions are essential. Restoring confidence and dispelling myths may be more therapeutic than any pill.

Fertility Considerations

Infertility is a major concern in male SCI patients, primarily due to ejaculatory dysfunction and compromised semen quality. Even when sperm are retrieved via PVS or EEJ, motility and morphology are often impaired, reflecting chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and recurrent infections of the genital tract.

Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) offer solutions. Intrauterine insemination (IUI) may succeed with adequate motile sperm counts, while in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) circumvent poor motility altogether. Success rates are comparable to those of non-SCI men once viable sperm are obtained.

For women, fertility is less directly affected, though secondary issues such as recurrent urinary infections, spasticity, or mobility limitations can complicate conception and pregnancy. Nonetheless, with appropriate multidisciplinary care, reproductive outcomes are favorable. The message to patients should be clear: SCI alters the path, but not the possibility, of parenthood.

Multidisciplinary Approaches and Counseling

Sexual rehabilitation in SCI is inherently multidisciplinary. Urologists address erectile and ejaculatory disorders; gynecologists manage lubrication and fertility; psychologists and sex therapists tackle the emotional dimensions. Rehabilitation nurses, occupational therapists, and peer counselors contribute practical insights on positioning, spasticity management, and adaptive devices.

Patient education is paramount. Many patients remain unaware that effective treatments exist. Structured programs that integrate lectures, counseling sessions, and practical workshops can demystify sexual rehabilitation. Peer support groups provide invaluable reassurance, normalizing concerns and sharing coping strategies.

Importantly, clinicians must initiate the conversation. Studies show that patients overwhelmingly want their providers to ask about sexual health, yet physicians often wait for patients to raise the issue. Given the taboos and vulnerabilities surrounding sexuality, this passive approach ensures silence. Proactive, empathetic inquiry should be standard practice.

Future Directions

Despite progress, major gaps remain. Pharmacological research continues to focus disproportionately on men, leaving female SCI patients underserved. Trials of PDE5 inhibitors and other vasodilators in women are promising but preliminary. Similarly, the neural mechanisms of orgasm and pleasure in SCI remain poorly understood, limiting therapeutic innovation.

Emerging technologies may help. Functional electrical stimulation (FES) holds potential for restoring genital responses. Advances in neuroprosthetics and spinal cord stimulation raise the possibility of reactivating disrupted reflex arcs. On the psychosocial side, virtual reality and telemedicine offer novel tools for counseling and partner training.

Ethically, the field must grapple with inclusivity. Sexual health should be viewed not as a luxury but as a fundamental component of rehabilitation. Policies and curricula should reflect this, ensuring that every patient receives comprehensive sexual counseling as a matter of course.

Conclusion

Sexual dysfunction after spinal cord injury is a complex, multifaceted challenge that touches physiology, psychology, and relationships. It is not an inevitable, untreatable fate but a medical condition amenable to intervention. PDE5 inhibitors, vibratory stimulation, assisted reproduction, lubricants, and prostheses all offer practical tools. Yet the real work lies in communication—breaking silence, dispelling myths, and restoring confidence.

For clinicians, the responsibility is clear: sexual health must be woven into the fabric of rehabilitation, not left as an afterthought. For patients, the message is hopeful: intimacy, pleasure, and parenthood remain achievable, though the path may look different than before. In embracing these realities, medicine can transform SCI from a life defined by loss into one enriched by adaptation, resilience, and renewed connection.

FAQ

1. Can men with spinal cord injury still father children?

Yes. While ejaculatory dysfunction and poor semen quality are common, assisted techniques such as penile vibratory stimulation, electroejaculation, and IVF/ICSI make biological fatherhood possible.

2. Do women with spinal cord injury lose fertility?

No. Most women retain normal fertility, though pregnancy requires careful management due to risks such as urinary infections and autonomic dysreflexia. With multidisciplinary care, outcomes are favorable.

3. Are sexual problems after SCI purely physical?

No. Psychological factors—depression, anxiety, loss of self-esteem, and relationship strain—are equally important. Effective management requires both medical treatment and psychosexual counseling.