Introduction: A Fast Reflex and a Slow Understanding

In medicine, some of the simplest phenomena turn out to be the hardest to explain. Premature ejaculation (PE) — often treated as a punchline in popular culture — remains one of the most complex, controversial, and understudied conditions in sexual medicine. For more than a century, physicians, psychiatrists, and pharmacologists have debated whether it is a disorder of the mind, the body, or perhaps both.

A recent comprehensive review by Jannini and colleagues titled “Premature Ejaculation: Old Story, New Insights” offers a fresh look at this familiar problem. Far from being a trivial inconvenience, PE profoundly affects both partners’ quality of life, self-esteem, and emotional intimacy. Its management has evolved from the psychoanalytic couches of the early 1900s to the pharmacological sophistication of the 21st century.

And yet, for all this progress, PE remains something of an enigma — a condition whose physiology is better described than understood, and whose treatment is more effective than curative.

The Natural History of Control

Ejaculation, in its evolutionary context, was designed for speed, not pleasure. Among primates, the act of copulation can last seconds — seven for chimpanzees, fifteen for bonobos, a few minutes for humans if they are lucky and mindful. Biologically speaking, ejaculation is a reflex designed to ensure reproduction under threat. Culturally speaking, humans have tried to slow it down ever since.

This “unnatural control” over ejaculation is a uniquely human invention. It is the byproduct of emotional bonding, partner awareness, and the pursuit of mutual pleasure. Thus, when a man struggles to delay ejaculation, the problem is not purely mechanical — it touches on the core of sexual communication and confidence.

Interestingly, the literature did not always view PE as a dysfunction. Kinsey’s landmark surveys in the 1940s found that most men ejaculated within two minutes of penetration — hardly pathological by zoological standards. But the sexual revolution of the 1960s, coupled with new attention to the female orgasm, reframed this quickness as a failure of control, not of biology.

From then on, PE entered the medical lexicon — first as a psychological disturbance, later as a neurochemical imbalance, and today as a multifactorial symptom that resists simple classification.

The Elusive Definition: How Short Is Too Short?

For decades, defining PE has been more a philosophical exercise than a scientific one. Masters and Johnson famously described it as the inability to delay ejaculation “until one’s partner is satisfied.” Elegant, but vague — and arguably sexist, since it equated female satisfaction entirely with male performance.

The American Psychiatric Association, in its DSM-5, attempted to quantify the unquantifiable: ejaculation within one minute of vaginal penetration, occurring “on almost all occasions” for at least six months. While this definition is practical for research, it excludes many men whose distress and relational strain are just as real but whose timing falls outside that rigid boundary.

The International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM) refined the concept further, distinguishing between lifelong (primary) and acquired (secondary) forms. The key diagnostic pillars are:

- Short intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT) — usually less than one minute;

- Loss of perceived control over ejaculation;

- Negative personal or relational consequences.

In essence, PE is defined not only by what happens (too fast) but by how it feels (loss of control and distress). It is one of the few male sexual dysfunctions where the partner’s perception is integral to diagnosis — a reminder that sex, after all, is a duet, not a solo performance.

Symptom or Disease? The Chicken and the Egg Dilemma

One of the most persistent debates is whether PE is a symptom of other underlying issues or a disease in its own right. Traditional models divided causes into “psychogenic” and “organic,” but such a dichotomy no longer holds. Every physical dysfunction carries psychological consequences, and every psychological disorder has a neurochemical substrate.

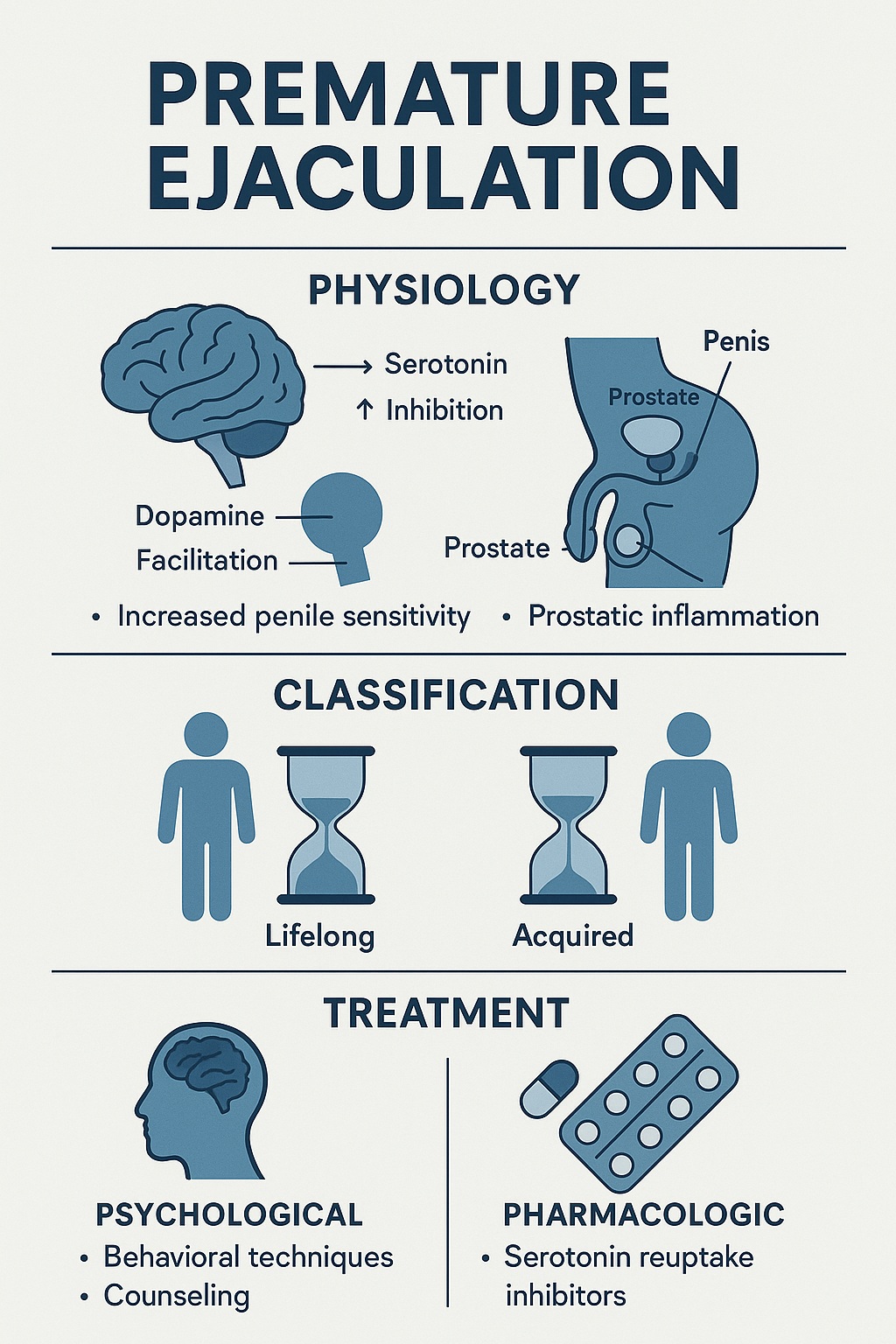

Modern understanding positions PE as a psycho-neuro-endocrine and urologic disorder — an interplay of serotonin signaling, hormonal balance, genital sensitivity, and emotional factors. In this view, PE is not “all in the head” or “all in the body.” It is the product of a finely tuned but occasionally overreactive reflex, shaped by mood, context, and partner dynamics.

Inside the Reflex: The Neurobiology of Ejaculation

Ejaculation is not a single event but a three-phase process:

- Emission – contraction of the male genital tract and release of seminal fluid.

- Ejaculation – rhythmic expulsion of semen through the urethra, largely reflexive.

- Orgasm – the subjective experience of pleasure, coinciding (usually) with ejaculation.

The central control of this reflex lies within the brainstem and hypothalamus. Two neurotransmitters play opposite roles: serotonin (5-HT), which delays ejaculation, and dopamine (DA), which accelerates it.

Serotonin acts as a natural brake on the ejaculatory reflex. Men with PE appear to have lower serotonergic tone, particularly involving the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2C receptor subtypes. This insight explains why certain antidepressants, which boost serotonin levels, can dramatically increase ejaculatory latency.

Conversely, dopamine, the neurotransmitter of reward and arousal, acts as the accelerator. The balance between these two systems — the serotonergic brake and the dopaminergic gas pedal — determines how quickly or slowly a man reaches climax.

It is perhaps no wonder that stress, anxiety, or guilt — all of which alter this neurochemical equilibrium — can transform a reflex into a crisis.

Beyond the Brain: The Peripheral and Hormonal Layers

While central control is crucial, the peripheral mechanisms of ejaculation are equally fascinating. Two gaseous neurotransmitters — nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) — play complementary roles. NO mediates erection, while CO participates in the emission and contraction phases.

Smooth muscle activity in the prostate, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens is regulated by calcium channels and Rho-kinase pathways, both sensitive to sex steroids. Even subtle changes in testosterone, oxytocin, or thyroid hormones can shift ejaculatory timing.

For example, hyperthyroidism often accelerates ejaculation, while hypothyroidism tends to delay it. Similarly, oxytocin, the so-called “cuddle hormone,” is released during orgasm and modulates both emotional bonding and muscle contraction.

Thus, hormonal and peripheral physiology intertwine with neurochemical control — making PE a multilayered system failure, not a single receptor glitch.

The Genetics and the Prostate: Unexpected Contributors

Early hypotheses suggested that PE might have a genetic basis, particularly involving polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene. However, twin studies reveal that heredity accounts for less than a third of the variance, leaving environmental, relational, and psychological influences as major determinants.

More recently, attention has turned to the prostate. Chronic prostatitis and inflammation may alter the sensory feedback from the genital tract, lowering the threshold for the ejaculatory reflex. Several studies show that treating prostatitis can improve ejaculatory control — a reminder that sometimes, the “sex problem” begins in a very urologic place.

In this light, PE may occasionally serve as a marker of underlying conditions, from infection to varicocele. A simple rectal exam, it seems, can sometimes solve what years of therapy cannot.

The Vicious Circle: PE, Erectile Dysfunction, and Anxiety

Up to half of men with PE also experience erectile dysfunction (ED) — an unfortunate but logical pairing. The two conditions feed off each other. A man anxious about losing his erection may rush intercourse, triggering premature ejaculation. Another, fearing PE, may consciously suppress arousal, resulting in erectile failure.

This vicious loop can quickly erode confidence and intimacy, leading to avoidance, frustration, and relational strain. The first rule of treatment, therefore, is to address erectile function before targeting ejaculation. No therapy will succeed if the patient is simultaneously battling ED, anxiety, and low desire.

Diagnosis: It Takes Two

Diagnosing PE is not just a matter of counting seconds. Modern assessment tools such as the Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (PEDT) and the Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP) help clinicians quantify control, satisfaction, and distress. Yet the most critical data often come from conversation — and from the partner.

A partner’s perspective provides context to the perceived problem. Many men underestimate or overestimate the duration of intercourse, while women’s experiences of dissatisfaction or emotional distance may point to underlying relational tension.

Therefore, clinicians are urged to evaluate the couple, not the individual, integrating psychological, relational, and physical data. The penis, after all, does not operate in isolation from the mind or the relationship.

Psychological Therapies: Reclaiming Control Without Pills

Before pharmacology, there was psychology. Behavioral techniques such as the stop–start and squeeze methods, pioneered by Masters, Johnson, and Kaplan, remain classics of sexual therapy. These interventions train men to recognize the “point of no return” — the threshold before inevitable ejaculation — and to gradually expand their window of control.

More contemporary approaches emphasize mindfulness, partner communication, and cognitive restructuring — addressing performance anxiety and the distorted expectations that surround male sexual performance.

Therapy is most effective when both partners are involved. Sexual counseling can dissolve guilt, reduce stress, and rekindle emotional connection — outcomes no pill can replicate. However, psychological methods require motivation, practice, and patience; they are slow medicine for a fast problem.

Pharmacological Interventions: Serotonin in a Capsule

The discovery that serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) could delay ejaculation was serendipitous. Men treated for depression often reported difficulty reaching orgasm — a side effect that turned into a therapeutic opportunity.

Drugs like paroxetine, sertraline, and fluoxetine can prolong IELT three- to tenfold, but their off-label use carries the baggage of antidepressant side effects: decreased libido, erectile problems, weight gain, and sleep disturbance. Moreover, these medications must be taken daily, making them unsuitable for occasional users.

Enter dapoxetine — the first officially approved, short-acting SSRI developed specifically for PE. With a rapid onset (about one hour) and quick clearance, dapoxetine can be taken on demand before intercourse. Clinical trials involving over 16,000 men show consistent benefits: a threefold increase in IELT, improved perceived control, and greater satisfaction for both partners.

Common side effects — nausea, dizziness, headache — are usually mild and transient. Unlike conventional SSRIs, dapoxetine has no withdrawal symptoms and minimal sexual side effects. When combined with PDE5 inhibitors (like sildenafil or tadalafil) in men with both PE and ED, it remains safe and effective.

Still, it is essential to remember that dapoxetine treats the symptom, not the system. Once discontinued, most men revert to baseline timing — underscoring that true healing lies not only in chemistry but in learning to manage arousal, anxiety, and connection.

Integrative Therapy: Where Medicine Meets Meaning

The best treatment for PE is rarely singular. The most successful outcomes arise from integrated approaches that combine pharmacologic aid with psychosexual guidance.

For instance, short-term dapoxetine therapy allows men to experience successful control, creating a “positive memory” of sexual confidence. Parallel counseling sessions can then help consolidate this newfound mastery into a durable habit. In this sense, medication becomes a training wheel, not a lifelong crutch.

Multidisciplinary cooperation — among andrologists, urologists, endocrinologists, and psychotherapists — ensures that both the neurochemical and emotional layers are addressed. After all, PE affects not just the individual but the couple’s dynamic, their trust, and even their sense of masculinity and femininity.

The Future of Understanding and Treatment

The story of premature ejaculation remains unfinished. Research continues into genetic markers, novel serotonergic modulators, and even oxytocin antagonists as potential therapies. Yet perhaps the next breakthrough will not come from a laboratory but from a clinic — from better definitions, more inclusive frameworks, and a shift from shame to empathy.

As Jannini eloquently concludes, we must abandon “opinion-based” dogma and embrace evidence-based compassion. PE is not a weakness but a condition, not a character flaw but a reflex imbalance — and, like any other medical issue, it deserves scientific rigor and human respect.

Conclusion: The Irony of Speed and the Wisdom of Patience

Premature ejaculation may be quick, but understanding it requires patience. From Freud’s couches to serotonin synapses, the journey has revealed as much about human intimacy as it has about neurophysiology.

We now know that PE is multifactorial, treatable, and deeply human. The best outcomes occur when biology, psychology, and partnership are treated together — when the goal shifts from lasting longer to connecting better.

Perhaps the final irony is that in learning to delay ejaculation, men often rediscover something more valuable than endurance: the art of slowing down, listening, and being present — in body, mind, and relationship.

FAQ: Premature Ejaculation Explained

1. Is premature ejaculation purely psychological?

No. While anxiety and performance pressure play major roles, PE involves neurochemical, hormonal, and even urologic factors. It is a multidimensional condition — psychological in expression, biological in mechanism.

2. Can medication cure premature ejaculation permanently?

Not yet. Drugs like dapoxetine or SSRIs improve control temporarily, but once discontinued, symptoms may recur. The most lasting results arise from combining medication with psychosexual therapy.

3. How long should a man last to be considered “normal”?

There is no universal “normal.” Most studies define PE as ejaculation within one minute of penetration, but satisfaction and control — not stopwatch timing — are what truly matter. Healthy sex is about mutual pleasure, not minutes.