Erectile dysfunction (ED) has transitioned in the last few decades from being a socially whispered embarrassment to a condition that is openly discussed in the clinic and vigorously investigated in the laboratory. The reason for this shift is straightforward: ED is not only a matter of intimacy, it is often the sentinel symptom of vascular and metabolic diseases that threaten overall health. At the same time, the pharmacological landscape for managing ED has expanded remarkably, moving from crude injections into penile tissue to sophisticated orally active small molecules that target specific enzymes. In this article, we will walk through the pharmacological history and present state of ED treatment, based on insights from foundational pharmacological research, including the comprehensive review by John A. Thomas (2002). The goal is to provide a clear yet critical perspective on where we stand in pharmacotherapy of ED.

The Physiology Behind Erectile Function

Before discussing pharmacology, we must revisit physiology. An erection is not a simple hydraulic reflex but a carefully orchestrated neurovascular event. It starts with psychogenic or reflexogenic stimuli that activate parasympathetic nerves. Nitric oxide (NO), released from endothelial cells and non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic nerves, diffuses into smooth muscle cells of the corpus cavernosum. There, NO stimulates guanylate cyclase, increasing cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), which triggers a cascade of intracellular events culminating in smooth muscle relaxation, arterial dilation, and venous occlusion—hence, penile rigidity.

This apparently elegant system is balanced by counter-regulators, most notably phosphodiesterases (PDEs), which break down cGMP. Among them, PDE5 dominates in cavernosal tissue. Thus, the fate of an erection can be determined by the tug-of-war between NO–cGMP signaling and PDE-mediated degradation. The insight may sound obvious today, but until the mid-1990s, it was far from intuitive.

When this signaling balance is disrupted—whether by endothelial dysfunction, neuropathy, or hormonal decline—the clinical result is ED. The challenge for pharmacology has always been to reinforce the deficient side of the pathway without derailing other physiological systems.

Early Pharmacological Approaches

Prior to the NO–cGMP revolution, treatment options were limited and often invasive. Several agents were used intrapenile or intraurethrally with mixed success and considerable discomfort. Their mechanisms targeted smooth muscle relaxation, though none were highly selective.

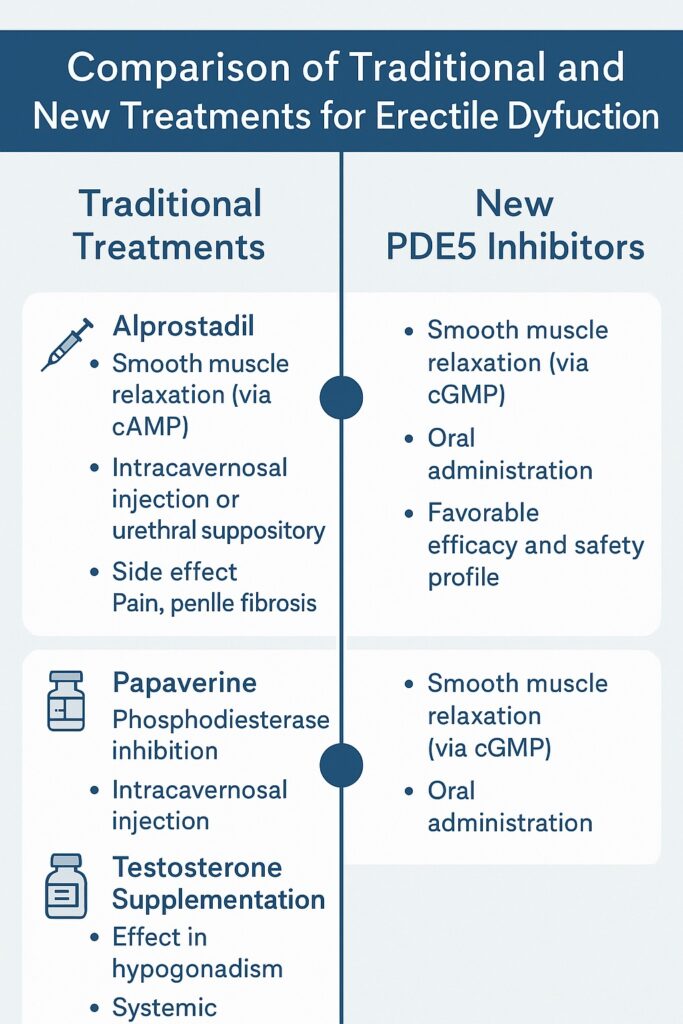

Alprostadil (prostaglandin E1) was one of the earliest reliable drugs. By increasing cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), it promoted cavernosal smooth muscle relaxation independent of NO. However, administration required either an injection directly into the corpora cavernosa or insertion of a urethral suppository—routes that were far from user-friendly. While effective, alprostadil was plagued by penile pain, fibrosis, and dropout rates that exceeded 50%. For many men, the “cure” felt worse than the disease.

Papaverine, a non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor, also earned early popularity. Its mechanism was pharmacologically appealing—broad elevation of cyclic nucleotides—but clinically problematic. Injections often caused priapism or fibrosis, and the drug lacked regulatory approval for ED in many countries. Combined with phentolamine, an α-adrenergic antagonist, efficacy improved, but so did the complication profile.

Testosterone supplementation was the pharmacological cornerstone for men with hypogonadism. When androgen deficiency is present, testosterone can restore libido and augment erectile capacity. Yet in eugonadal men, its benefits were marginal, underlining the importance of diagnosis before prescription.

These agents collectively set the stage: pharmacological manipulation of cavernosal smooth muscle was possible, but efficacy, tolerability, and patient acceptability remained unsatisfactory.

The Sildenafil Revolution

The 1998 introduction of sildenafil citrate, the first oral PDE5 inhibitor, transformed ED management and arguably the cultural discourse around male sexual health. Originally developed as a potential anti-anginal agent, sildenafil fortuitously demonstrated a profound effect on penile erections. Its mechanism—selective inhibition of PDE5—allowed cGMP to accumulate in cavernosal tissue, amplifying the natural erectile response to sexual stimulation.

The significance cannot be overstated. For the first time, ED could be treated with a pill that was effective, relatively safe, and discreet. Clinical trials showed response rates of 60–80%, far surpassing invasive predecessors. Moreover, the drug did not create erections in the absence of arousal; instead, it potentiated physiological pathways. This subtlety made sildenafil socially acceptable, aligning pharmacology with natural intimacy.

Of course, sildenafil was not perfect. Its selectivity for PDE5 was not absolute, and inhibition of PDE6 in retinal tissue explained visual disturbances, including blue-tinged vision. Headaches, flushing, and dyspepsia were common but generally mild. The contraindication with nitrates, due to the risk of profound hypotension, demanded vigilance. Yet these drawbacks were overshadowed by the clinical and commercial triumph.

Expansion Beyond Sildenafil: The PDE5 Inhibitor Class

Pharmacological competition quickly followed. Tadalafil and vardenafil were developed as “second-generation” PDE5 inhibitors, each offering unique pharmacokinetic advantages. Tadalafil, with its 17-hour half-life, earned the moniker “the weekend pill,” allowing greater spontaneity. Vardenafil provided faster onset and slightly higher potency, though its clinical differentiation was modest.

The expansion of the PDE5 class highlighted an important lesson: while all inhibit PDE5, subtle differences in pharmacology translate into real-world preferences. Some patients prefer the long duration of tadalafil; others find sildenafil’s shorter action sufficient. The existence of multiple options reduced stigma, normalized treatment, and forced prices downward, improving accessibility.

Still, PDE5 inhibitors were not universal panaceas. Efficacy rates, though high, left 20–40% of men dissatisfied, especially those with severe diabetes, radical prostatectomy, or advanced vascular disease. Clearly, pharmacology needed backup plans.

Alternative Pharmacological Pathways

Not all men are candidates for PDE5 inhibition, and not all erections depend solely on cGMP. Researchers turned to alternative neurotransmitters and receptors for inspiration. One such avenue was dopaminergic modulation. Apomorphine, a D1/D2 receptor agonist, was tested as a sublingual therapy. By acting centrally on hypothalamic pathways, it aimed to trigger erection initiation. While pharmacologically elegant, apomorphine disappointed clinically. Efficacy was modest, and side effects such as nausea curtailed enthusiasm.

Other experimental strategies included Rho-kinase inhibitors and guanylate cyclase activators. These agents directly targeted smooth muscle tone or attempted to bypass NO dependence. Preclinical data were compelling, but translation to clinical practice has been halting. The difficulty lies in balancing penile selectivity with systemic safety. After all, lowering vascular tone too broadly risks hypotension, a side effect unacceptable in chronic therapy.

Hormonal modulation remains relevant for a minority of men. In hypogonadism, testosterone replacement is not merely symptomatic treatment but physiological correction. Yet its role as a primary therapy for ED is limited, and safety debates surrounding cardiovascular risk persist.

Combination Therapies: Synergy or Redundancy?

Pharmacologists are rarely content with monotherapy. The combination of PDE5 inhibitors with testosterone has been explored in men with suboptimal responses. In hypogonadal men, synergy appears real: testosterone restores androgen-dependent pathways, while PDE5 inhibition enhances cGMP signaling. Clinical trials suggest that this combination rescues a subset of non-responders.

Similarly, alprostadil remains relevant as adjunctive therapy. Intracavernosal or intraurethral alprostadil combined with PDE5 inhibitors can overcome resistance in severe ED. Yet, the invasiveness of administration keeps it as second-line therapy.

The broader lesson is that ED is not monolithic. Pathophysiology varies, and so should pharmacological strategies. Combination therapy exemplifies personalized medicine, though practical barriers such as cost, adherence, and regulatory approval temper enthusiasm.

Safety Considerations and Adverse Effects

No pharmacological discussion is complete without safety. PDE5 inhibitors are generally safe but not risk-free. The nitrate contraindication remains absolute. Visual disturbances, while usually benign, highlight off-target effects. Rare reports of hearing loss and priapism demand ongoing vigilance.

Alprostadil and papaverine, though effective, carry risks of fibrosis and penile pain. Testosterone therapy, meanwhile, raises perennial debates about prostate safety and cardiovascular outcomes, despite conflicting evidence.

What is clear is that pharmacotherapy for ED cannot be divorced from cardiovascular assessment. The Princeton Consensus underscores that ED is often the first clinical manifestation of systemic vascular disease. Prescribing sildenafil without considering underlying coronary pathology is not only negligent but potentially dangerous.

The Future of Pharmacological Research

The pharmacological journey of ED is far from over. Future strategies are likely to focus on molecular precision and regenerative approaches. Gene therapy, stem cell transplantation, and novel signal modulators are under investigation. The dream is not merely to manage symptoms but to restore erectile physiology permanently.

Another frontier is female sexual dysfunction, where sildenafil and related agents have been trialed with mixed results. While the pathophysiology differs, the pharmacological ambition remains similar: amplify natural responses without overriding them.

Finally, accessibility and destigmatization are paramount. Pharmacological advances matter little if patients cannot afford or are too embarrassed to access therapy. In this sense, sildenafil’s greatest legacy may not be its mechanism of action but its cultural impact.

Conclusion

Erectile dysfunction pharmacology exemplifies the arc of modern therapeutics: from invasive and poorly tolerated agents to targeted, orally effective, and socially acceptable drugs. The arrival of sildenafil was a watershed moment, but its success should not obscure the continued need for innovation. Not all men respond, not all etiologies are addressed, and safety considerations remain real.

Pharmacologists, clinicians, and patients must navigate between efficacy, tolerability, and personalization. The field has come far, but the ultimate goal—safe, universal, restorative therapy—remains on the horizon.

FAQ

1. Why do PDE5 inhibitors not work for everyone with ED?

Because ED has diverse causes. In men with severe diabetes, radical prostatectomy, or advanced vascular disease, the NO–cGMP pathway may be too compromised for PDE5 inhibition alone to be effective. Structural nerve damage, fibrosis, or hormonal deficits can blunt response.

2. Is testosterone therapy a good option for all men with ED?

No. Testosterone is beneficial in men with documented hypogonadism but offers little to eugonadal men. Moreover, long-term safety, particularly regarding prostate and cardiovascular risks, remains debated. Testing before treatment is essential.

3. Are PDE5 inhibitors safe for men with heart disease?

Generally yes, provided nitrates are not used concomitantly. PDE5 inhibitors themselves are not cardiotoxic, but their vasodilatory effects can dangerously potentiate nitrate therapy. Cardiovascular evaluation should always precede prescribing in at-risk men.