Introduction

Few medical topics are as misunderstood—and as surrounded by silence—as female sexual dysfunction. Among its subcategories, Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder (FSIAD) stands out, not because it is rare, but because it is so common and yet so undertreated. At its core, FSIAD reflects a persistent or recurrent lack of interest in sexual activity and diminished arousal, often accompanied by distress. In a culture where sexual health is still often relegated to whispers, this condition has remained hidden in the shadows, even as its prevalence rivals that of more commonly discussed chronic illnesses.

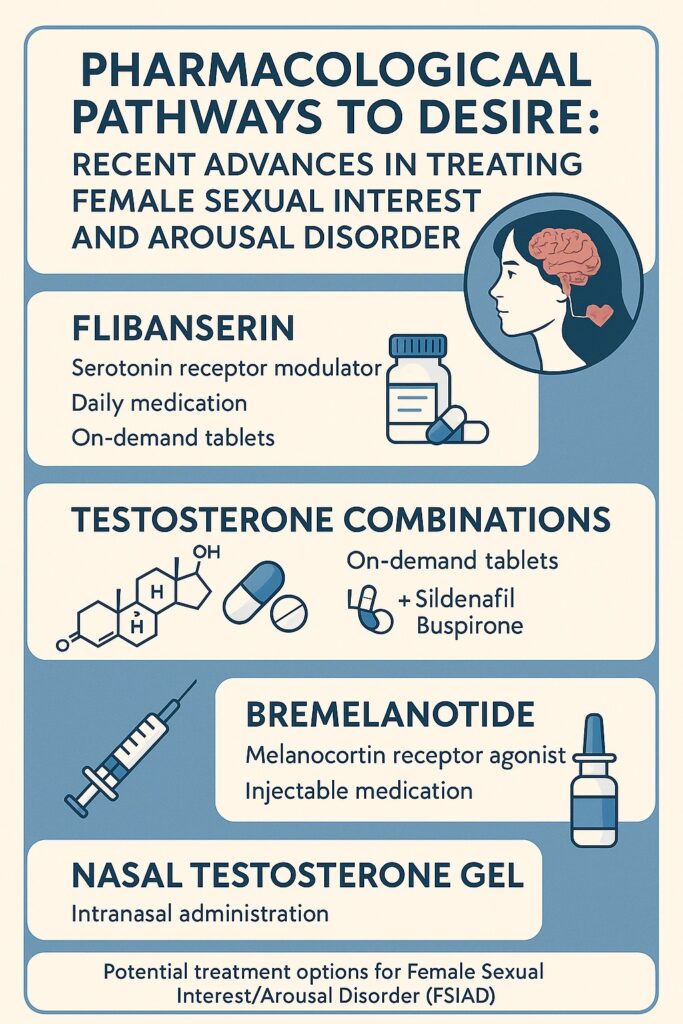

Over the last decade, psychopharmacology has taken an ambitious interest in addressing female sexual desire. What began with flibanserin—the first FDA-approved drug for premenopausal women with low sexual desire—has since expanded to include experimental therapies such as testosterone combined with sildenafil (Lybrido), testosterone with buspirone (Lybridos), bremelanotide, intranasal testosterone gels (TBS-2), BP101 peptide molecules, and even cognitive enhancers such as d-cycloserine. Each of these candidates seeks to modulate the delicate interplay of neurochemical excitation and inhibition that governs female sexual responsiveness.

Yet, despite the innovation, the results so far remain modest. For many women, the pharmaceutical promise of “rekindled desire” translates clinically to just one additional satisfying sexual event per month—an outcome that may raise eyebrows about the true therapeutic significance. And so, the conversation continues: are we on the cusp of a pharmacological breakthrough, or simply circling the same questions with shinier molecules?

Understanding FSIAD: Definitions and Prevalence

FSIAD is more than “low libido.” It is clinically defined in the DSM-5 as a persistent or recurrent lack of sexual interest and/or arousal, diagnosed only when symptoms persist for at least six months and cause significant distress. Importantly, the disorder cannot be explained away by another mental health condition, medical illness, or substance use. Nor should it be confused with the natural ebb and flow of desire across the lifespan, or the all-too-common mismatch of sexual appetites between partners.

For diagnosis, clinicians must look for at least three of six hallmark symptoms, ranging from reduced erotic thoughts and fantasies to diminished genital sensations. This is where subjectivity complicates matters. Unlike hypertension, FSIAD cannot be measured with a cuff. Instead, it is grounded in clinical judgment and the woman’s own distress, which makes it as much a relational diagnosis as an individual one.

Prevalence estimates vary, but studies consistently show that 20–30% of women report low sexual desire, though only half of them experience it as distressing enough to warrant a diagnosis. Arousal problems are similarly common, affecting 11–31% of women, but again the rates fall sharply when distress is used as the defining criterion. In other words, the condition is widespread, but not universally troubling. This distinction—between experiencing low desire and suffering from it—is essential. After all, not every woman considers sex to be the cornerstone of personal fulfillment, despite what glossy magazines may suggest.

Mechanisms of Sexual Interest and Arousal

If only desire were as simple as flipping a neurochemical switch. Instead, it emerges from a complex symphony of internal physiology, external stimuli, cognitive processing, and relational context. Modern theories, such as the incentive motivation model, emphasize that sexual motivation is not an innate drive but rather a state that arises when three conditions align: a responsive sexual system, the presence of sexually meaningful stimuli, and favorable circumstances for intimacy.

On the neurobiological level, sexual responsiveness is governed by a delicate balance between excitatory and inhibitory processes. Excitatory agents include testosterone, dopamine, norepinephrine, oxytocin, and melanocortins, while inhibitory forces are driven by serotonin, opioids, and endocannabinoids. A tilt too far toward inhibition—or an underperforming excitatory system—can leave desire stranded.

Beyond chemistry, psychology plays an equally decisive role. Distracting thoughts, body image concerns, or negative sexual experiences can sabotage arousal even in the most biochemically primed individual. Moreover, cultural and relational dynamics—such as a lack of intimacy, communication difficulties, or sexual trauma—often overshadow pharmacological tinkering. In this sense, FSIAD is less a “disease of the brain” and more a condition of the whole person.

Flibanserin: A Pioneering, If Modest, First Step

When flibanserin (brand name Addyi) gained FDA approval in 2015, it was heralded as the “female Viagra.” The comparison was misleading. While sildenafil boosts genital blood flow, flibanserin works centrally, modulating serotonin and dopamine receptors in the brain. Originally designed as an antidepressant, it was repurposed after some women reported improved sexual responsiveness—a serendipitous side effect turned therapeutic mission.

Clinical trials revealed statistically significant improvements, yet the magnitude was underwhelming. Women reported about one additional satisfying sexual event per month compared to placebo. Side effects—dizziness, somnolence, nausea, fatigue, and dangerous interactions with alcohol—further complicated its reception. The medical community was divided: was this a long-overdue recognition of women’s sexual health, or a triumph of pharmaceutical marketing over meaningful efficacy?

The debate continues, but flibanserin’s approval set an important precedent: sexual desire in women is not a frivolous luxury, but a legitimate medical concern worthy of pharmacological intervention. Still, the search for more effective and tolerable options remains urgent.

Testosterone Combinations: Lybrido and Lybridos

The dual control model of sexual response posits that desire reflects the balance between excitatory and inhibitory brain processes. Building on this, researchers developed two “personalized” therapies:

- Lybrido: testosterone combined with sildenafil, aimed at women with low sensitivity to sexual cues.

- Lybridos: testosterone combined with buspirone, targeted at women with excessive sexual inhibition.

Both are designed for on-demand use, administered four hours before anticipated intimacy—an approach that avoids prolonged androgen exposure and offers women agency over timing. Early studies showed that women with low cue sensitivity experienced significantly stronger genital and subjective arousal with Lybrido, while those with high inhibition benefited from Lybridos. Reported side effects were mild, including flushing, headache, or dizziness.

The catch? Sample sizes were small, and reliable methods for distinguishing “low sensitivity” from “high inhibition” subgroups are not yet validated. Promising though the results may be, without large-scale trials and clearer diagnostic frameworks, Lybrido and Lybridos remain more hopeful concepts than established treatments.

Bremelanotide: Harnessing the Melanocortin Pathway

If flibanserin is the cautious academic, bremelanotide is the bold experimenter. A melanocortin receptor agonist, bremelanotide stimulates dopaminergic activity in the medial preoptic area—a brain region central to sexual behavior. Administered via subcutaneous injection 45 minutes before anticipated activity, it aims to directly boost sexual motivation.

In phase II trials, women using bremelanotide reported modest gains: about 0.5 more satisfying sexual events per month than placebo, alongside improvements in desire and distress scores. Side effects—especially nausea—were common, though generally manageable. The effect size, however, remains disappointingly small. For many clinicians, the question lingers: is half an extra satisfying event per month worth a needle in the thigh and a spell of nausea?

Nevertheless, bremelanotide represents an exciting mechanistic pathway, distinct from serotonergic manipulation, and underscores the willingness of researchers to explore unconventional neurochemical routes.

Nasal Testosterone Gel (TBS-2): Fast-Acting Intrigue

The intranasal testosterone gel TBS-2 offers a novel delivery system with rapid central action. Early trials compared its effects with the transdermal Intrinsa patch and placebo. Women reported stronger subjective arousal, positive mood, and genital responses, particularly within hours of administration. Importantly, plasma testosterone levels remained within normal limits, addressing safety concerns about androgen exposure.

In studies involving women with anorgasmia, TBS-2 enhanced genital responses and increased reported arousal during erotic stimulation. Some participants even achieved orgasm during controlled trials—an outcome that, while not statistically significant, is clinically tantalizing. Whether TBS-2 advances beyond experimental phases will depend on larger trials, but the appeal of a fast-acting, discreet nasal spray is undeniable.

BP101: A Synthetic Peptide in Early Trials

Sometimes science reads like fiction. BP101, a synthetic peptide of undisclosed structure, has shown intriguing effects in animal studies, particularly in enhancing solicitation behavior in female rats. Its mechanism seems tied to action in the medial preoptic area, a hub of sexual motivation. Human trials are now underway, exploring nasal administration in women with hypoactive sexual desire.

The challenge here is opacity: without knowing BP101’s exact structure or molecular targets, enthusiasm is tempered. Yet the mere fact that it is advancing through phase II studies speaks to the hunger for novel therapeutic directions. Whether BP101 becomes a footnote or a future standard remains to be seen.

D-Cycloserine and the Marriage of Memory and Therapy

Not all pharmacological innovation focuses on neurotransmitters directly. D-cycloserine (DCS), a partial NMDA receptor agonist known to enhance memory processes, has been studied as an adjunct to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). By strengthening extinction learning, DCS may help women unlearn negative associations with sexual cues and reinforce positive experiences during sex therapy.

Initial studies suggest that DCS can enhance both extinction and acquisition of conditioned sexual responses, potentially amplifying the effectiveness of CBT. Here, the drug is not a “desire pill” but a memory facilitator, helping women rewrite the script of their sexual learning. This approach elegantly illustrates that pharmacology and psychotherapy need not compete but can collaborate for greater impact.

The Bigger Picture: Beyond Pills

While pharmacological research is advancing, it is essential not to lose sight of the broader context. Desire is not generated in a vacuum. A woman with a history of sexual trauma, unresolved relationship conflict, or inadequate sexual education will not find her challenges solved by a pill—however sophisticated its molecular action. As many experts argue, treating the couple, not just the woman, often yields better results.

Equally important is managing expectations. For a woman hoping to rediscover a vibrant sex life, the reality of “one extra satisfying event per month” may feel underwhelming. Clinicians must navigate this terrain carefully, balancing hope with honest discussion of likely outcomes, side effects, and the importance of parallel psychotherapeutic interventions.

Conclusion

The quest to pharmacologically rekindle female sexual desire is both noble and fraught with complexity. Drugs like flibanserin, Lybrido, Lybridos, bremelanotide, TBS-2, BP101, and d-cycloserine offer glimpses of possibility but, so far, modest clinical significance. Desire, after all, is not a switch but a symphony, requiring harmony between biology, psychology, and relational dynamics.

In the years ahead, success will likely come not from a single “female Viagra” but from integrated approaches—pharmacological agents that complement therapy, relational work, and education. Until then, clinicians and patients must embrace both scientific rigor and a touch of humility: the human brain is not so easily persuaded to love, lust, or long.

FAQ

1. Are drugs like flibanserin and bremelanotide truly effective for FSIAD?

They can help, but the effects are modest—typically one additional satisfying sexual event per month compared to placebo. Side effects and daily use requirements also limit their appeal. They are best seen as adjuncts, not cures.

2. Why combine testosterone with sildenafil or buspirone?

These combinations target different pathways. Testosterone enhances excitatory processes, while sildenafil increases genital blood flow and buspirone reduces sexual inhibition. Together, they may restore balance in women with specific neurochemical profiles.

3. Can therapy alone be enough without drugs?

Yes. For many women, especially those with relational issues, trauma histories, or cognitive barriers, psychotherapy and sex therapy may be more impactful than medication. The most effective strategies often combine both approaches.