Introduction

Infertility remains one of the most challenging conditions for modern reproductive medicine. Affecting an estimated 10–15% of couples worldwide, it is not merely a medical problem but also an emotional and social one. The cornerstone of treatment for many women with ovulatory dysfunction is ovulation induction—the process of pharmacologically stimulating the ovaries to produce and release oocytes. For decades, the debate has revolved around which pharmacologic agents are safest, most effective, and most cost-efficient in both natural and assisted reproductive cycles.

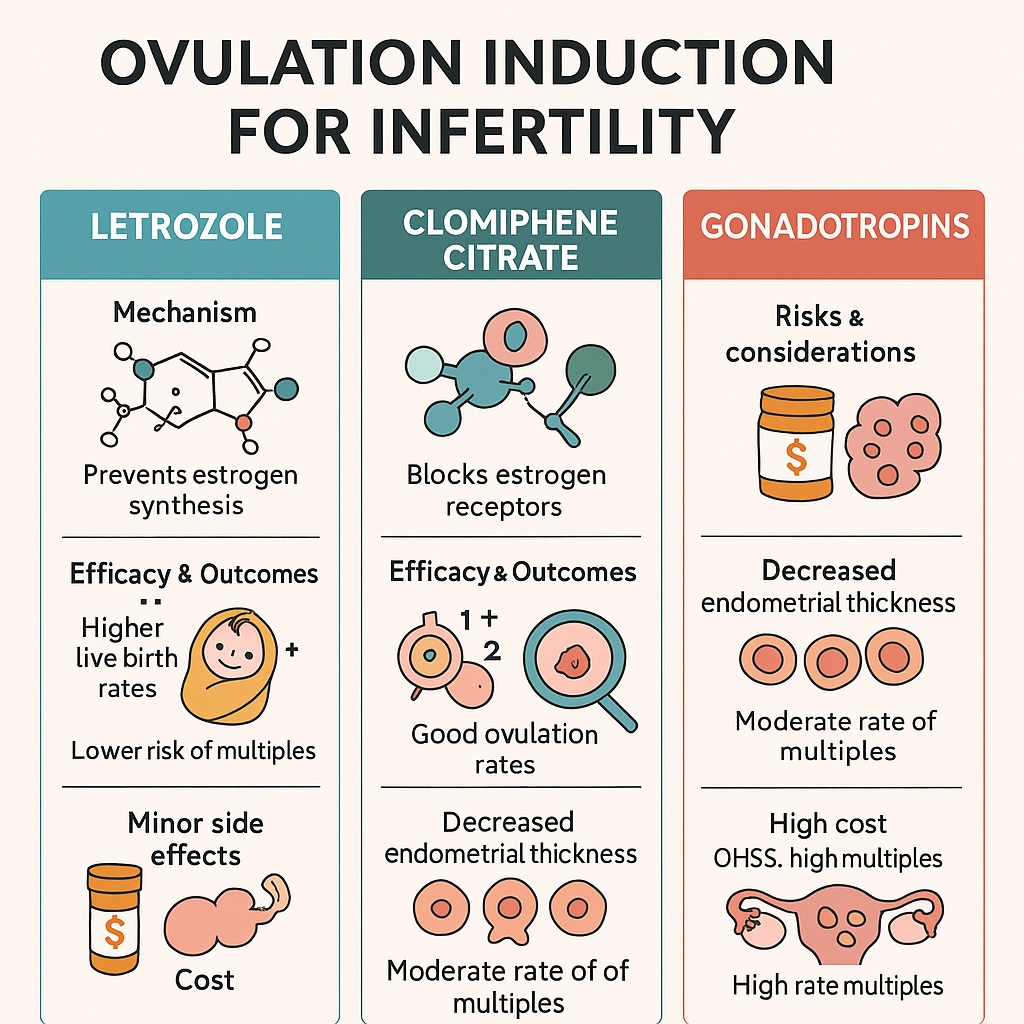

Clomiphene citrate, introduced in the 1960s, once dominated the landscape as the first-line oral therapy. However, newer agents such as letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, have challenged its reign. In parallel, gonadotropins remain highly effective, though more costly and associated with risks such as ovarian hyperstimulation and multiple pregnancy. The study underlying this discussion compares these approaches, aiming to refine best practices and help physicians tailor treatment to the individual patient rather than rely on dogma.

This article synthesizes those findings and expands them into a broader exploration of ovulation induction strategies, weighing clinical efficacy, safety, and patient-centered considerations. The aim is to provide a professional yet approachable guide to what the evidence tells us—and what questions remain.

The Evolution of Ovulation Induction

The history of ovulation induction reflects the broader evolution of reproductive medicine. In the mid-20th century, clomiphene citrate became a game-changer. As a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), it works by blocking estrogen receptors at the hypothalamus, leading to increased secretion of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). The outcome: follicular growth and ovulation.

For many years, clomiphene was the standard choice. It was inexpensive, orally administered, and produced ovulation rates of 60–85%. Yet, it was never perfect. Its anti-estrogenic effects on the endometrium and cervical mucus reduced pregnancy rates relative to ovulation rates. Furthermore, prolonged use sometimes led to resistance, necessitating escalation of therapy.

The introduction of aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole in the early 2000s marked a paradigm shift. Unlike clomiphene, letrozole does not exert persistent anti-estrogenic effects. Instead, by inhibiting aromatase, it reduces estrogen synthesis, thereby lifting negative feedback at the hypothalamus and stimulating gonadotropin release. Its shorter half-life and more physiologic endometrial environment have made it particularly attractive. Over time, evidence has accumulated suggesting that letrozole may outperform clomiphene, especially in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Gonadotropins, derived initially from urine and later through recombinant technology, represent a more direct and potent approach. By bypassing the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, they directly stimulate the ovaries. Although effective, they carry significant costs and risks, making them less suitable as first-line therapy but highly valuable in resistant cases or assisted reproduction.

Clomiphene Citrate: The Old Guard

Clomiphene citrate deserves recognition for its historical role, but critical appraisal reveals its limitations.

First, while ovulation induction rates are strong, pregnancy and live birth rates lag behind. Studies suggest that only about 20–25% of women achieve live birth after several cycles of clomiphene. This discrepancy is partly explained by its adverse endometrial effects: thinning of the lining and reduced receptivity. For a medication intended to promote conception, this paradox is difficult to ignore.

Second, clomiphene resistance—defined as failure to ovulate after several cycles—affects up to 20% of women, particularly those with PCOS. This necessitates moving to alternative therapies, adding time, cost, and emotional burden.

Third, the risk of multiple pregnancy, though lower than with gonadotropins, is still present. Twins occur in 5–8% of clomiphene cycles, an outcome that may sound appealing to some patients but complicates pregnancy care and increases perinatal risks.

Despite these drawbacks, clomiphene remains in use, largely due to its low cost and oral administration. In resource-limited settings, it is often the only accessible first-line agent. But where alternatives are available, its supremacy has waned.

Letrozole: The Rising Star

Letrozole emerged not from reproductive medicine but from oncology, originally developed to suppress estrogen in hormone-sensitive breast cancer. Its repurposing for ovulation induction exemplifies medical ingenuity.

The advantages of letrozole are increasingly clear. Unlike clomiphene, it does not block estrogen receptors, meaning the endometrium retains its receptivity. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have demonstrated superior pregnancy and live birth rates with letrozole compared to clomiphene, especially in PCOS populations. Notably, the landmark PPCOS II trial (2014) showed a significantly higher live birth rate with letrozole (27.5% vs. 19.1% for clomiphene).

Moreover, letrozole induces monofollicular development more often than clomiphene, reducing the risk of multiple pregnancy. From a safety perspective, this is a substantial gain. The long-feared concern that aromatase inhibitors might increase congenital malformations has not been borne out by large-scale studies, providing reassurance about its safety profile.

Still, letrozole is not without challenges. Its cost, though modest, is generally higher than clomiphene. Its use may also be constrained in some regions by regulatory approval status, as not all countries formally approve it for infertility treatment. Nevertheless, it is increasingly recognized as the preferred oral agent in evidence-based practice.

Gonadotropins: Potent but Perilous

Gonadotropins occupy a unique position. They are undeniably effective, often succeeding where oral agents fail. Recombinant FSH and LH formulations allow precise dosing, and in assisted reproduction, gonadotropins are indispensable.

However, the risks cannot be understated. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) remains the most feared complication, though modern protocols and antagonist regimens have reduced its incidence. Multiple pregnancy rates are also significantly higher, sometimes exceeding 20% without careful monitoring. These outcomes impose clinical, emotional, and economic costs.

Furthermore, gonadotropins require subcutaneous or intramuscular injections, regular monitoring with ultrasound and bloodwork, and significant financial resources. This makes them impractical for widespread first-line use. Instead, their role is best seen as second- or third-line, reserved for women resistant to oral agents or as part of in vitro fertilization (IVF) protocols.

Nonetheless, for selected patients—those with hypothalamic amenorrhea, for example—gonadotropins remain the therapy of choice. The key lies in tailoring their use, minimizing risks, and ensuring close monitoring.

Beyond Efficacy: Considering the Patient

When comparing ovulation induction strategies, it is tempting to focus solely on numbers: ovulation rates, pregnancy rates, live births. But fertility care is never just about statistics; it is about people navigating one of the most emotionally fraught journeys of their lives.

Patients care about effectiveness, yes, but also about safety, convenience, and affordability. A woman juggling work and family responsibilities may prefer an oral agent to daily injections. Another may prioritize minimizing the risk of multiple pregnancy. For couples paying out of pocket, cost often trumps theoretical efficacy.

Therefore, the art of reproductive medicine lies not in declaring a universal “best” drug but in tailoring the choice to each patient. Clomiphene may remain a reasonable starting point in low-resource settings. Letrozole offers superior outcomes for many, especially those with PCOS. Gonadotropins provide a powerful option when simpler agents fail. The true skill is knowing when—and for whom—to use each.

The Future of Ovulation Induction

The field is far from static. Advances in pharmacogenomics may one day allow clinicians to predict which women will respond to which agents, eliminating the frustrating trial-and-error process. Novel molecules are under investigation, including selective estrogen receptor degraders (SERDs) and kisspeptin analogues, which may offer new avenues of stimulation with improved safety.

Furthermore, technology is reshaping monitoring. Home urine hormone tests, wearable devices, and artificial intelligence algorithms promise to reduce the need for intensive clinic visits, making ovulation induction more patient-friendly. As with many areas of medicine, the future will likely involve personalization, harnessing data to tailor therapy more precisely than ever before.

Yet even as innovation continues, the lessons of the present remain clear: letrozole has displaced clomiphene as the most effective oral agent, gonadotropins remain essential but high-risk, and patient-centered decision-making is paramount.

Conclusion

The comparison of letrozole, clomiphene citrate, and gonadotropins underscores a central truth of reproductive medicine: no single therapy suits all patients. Clomiphene, while historically important, is increasingly outdated due to its anti-estrogenic drawbacks. Letrozole has emerged as a superior first-line choice, particularly in PCOS, with higher live birth rates and lower risks of multiples. Gonadotropins retain a vital but more specialized role, offering powerful stimulation at the cost of greater risks and resource demands.

In the end, the best treatment is not dictated by tradition or even by clinical trial data alone but by a nuanced balance of science, patient preference, and context. Ovulation induction is both a medical intervention and a profoundly human journey—and the wise clinician recognizes both dimensions.

FAQ

1. Why is letrozole now preferred over clomiphene citrate for many patients?

Letrozole provides higher live birth rates and avoids the anti-estrogenic effects of clomiphene, preserving endometrial receptivity. It also reduces the risk of multiple pregnancy compared to both clomiphene and gonadotropins.

2. Are gonadotropins unsafe?

Not inherently, but they carry higher risks of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and multiple pregnancy. With careful monitoring, these risks can be managed. Their main drawbacks are cost, invasiveness, and the need for close supervision.

3. How should patients and doctors decide which agent to use?

The choice depends on clinical factors (such as PCOS or hypothalamic amenorrhea), previous treatment responses, cost, and patient preference. Shared decision-making, grounded in evidence but sensitive to personal circumstances, remains the gold standard.