Introduction: When Chemistry Enters the Bedroom

Sex, once considered the most natural of human activities, is now often mediated by chemistry. Pills, patches, and potions have infiltrated the intimate domain, promising performance, endurance, and satisfaction — sometimes even love itself, in tablet form. In the United Kingdom, this transformation has been quietly documented by one of the most ambitious population studies ever conducted: the Third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3).

Conducted between 2010 and 2012 across a representative British sample of over 15,000 adults aged 16–74, this study lifted the curtain on what might be called pharmacosexual Britain. Its findings are illuminating, sometimes sobering, and occasionally ironic. They reveal a society where medicated sex — that is, sexual activity assisted by pharmacologic agents such as sildenafil (Viagra) or other performance-enhancing substances — is no longer exceptional but quietly normalized.

In the following analysis, we will unpack the data and meaning of this study — exploring who uses sexual performance medications, why they do so, and what it tells us about the intersection between medicine, behavior, and modern sexuality.

The Evolution of Medicated Sex: From Cure to Culture

The introduction of sildenafil citrate (Viagra) in the late 1990s marked a profound shift in both medical practice and sexual culture. What began as a targeted treatment for erectile dysfunction (ED) rapidly evolved into a symbol of masculine rejuvenation and even “sexual insurance.” Over time, use of PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil, tadalafil, and vardenafil has spread far beyond the population of men with diagnosed ED.

For women, the story has been more complicated. Despite numerous attempts to develop a “female Viagra,” pharmacological solutions for low libido or sexual arousal disorders have had limited success and often raised safety concerns. Testosterone supplementation, for instance, remains tightly regulated, and other agents have failed to secure approval due to marginal benefits and disproportionate risk.

Beyond prescribed use, the last two decades have witnessed the rise of informal or recreational use. Some men — particularly younger or high-risk groups — take PDE5 inhibitors without medical supervision, often alongside alcohol or recreational drugs such as methamphetamine, cocaine, or “poppers” (amyl nitrates). This behavior blurs the line between therapy and enhancement, between treatment and indulgence.

Thus, by the time Natsal-3 was conducted, the term “medicated sex” encompassed a broad spectrum:

- Formal use, prescribed by clinicians to address diagnosed dysfunctions; and

- Informal use, involving self-medication, off-label use, or recreational combinations aimed at intensifying experience.

Each reflects a facet of modern sexuality: the desire for performance, control, and reassurance — often pursued through pharmacological means.

Study Design: Capturing the Intimate Reality of a Nation

The Natsal-3 survey used a cross-sectional probability sample of the British population, encompassing 6,293 men and 8,869 women. Participants were interviewed in their homes using computer-assisted self-interviewing — a method designed to preserve privacy and encourage honest responses on sensitive topics such as sexual behavior and drug use.

Respondents were asked whether they had ever used medication or pills “to assist sexual performance,” explicitly including drugs like Viagra and excluding the need for a prescription. Those who answered “yes” were then asked when they last did so.

Statistical analysis incorporated demographic factors, sexual behavior, substance use, and self-reported sexual function. Logistic regression was applied to control for confounders such as age, same-sex behavior, and erectile dysfunction.

In short, this was not a study of men in clinics or students in dormitories, but a panoramic portrait of the sexual pharmacology of Britain — spanning ages, relationships, and lifestyles.

Who Uses Medication for Sex — and Why?

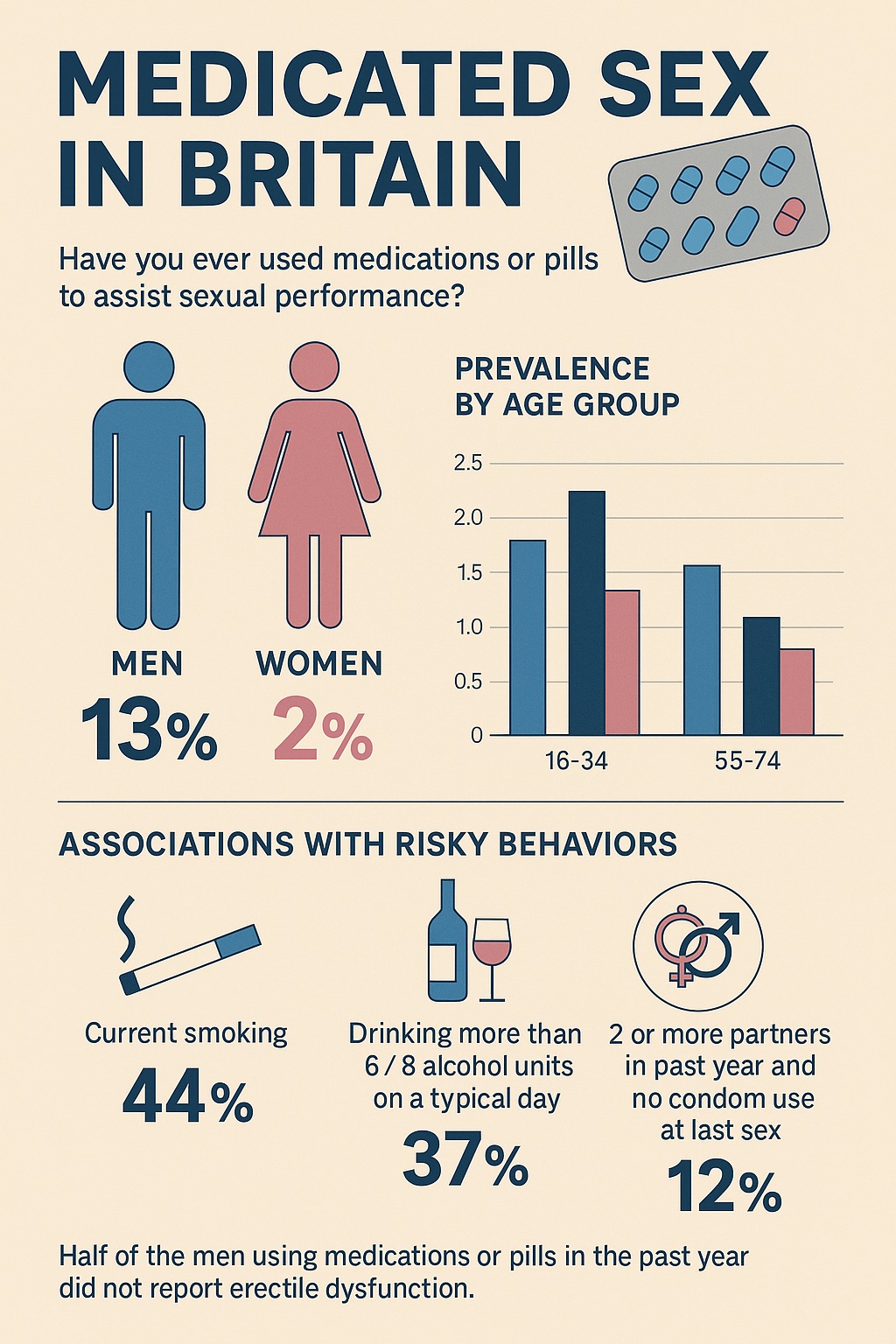

The findings were both expected and revealing. Approximately 12.9% of sexually experienced men and 1.9% of sexually experienced women reported having used medication to aid sexual performance at some point in their lives.

Gender and Age Differences

As anticipated, men were far more likely than women to report medicated sex — roughly six times as likely. Among men, use increased steadily with age: those aged 55–74 were over twice as likely as younger men to have tried such medication. For women, the pattern was reversed — younger women were more likely to report medicated sex than older ones, though the absolute numbers remained very small.

These findings reflect both the availability and cultural legitimacy of sexual medication for men and the persistent lack of effective pharmacological options for women.

Health and Lifestyle Correlates

Men and women who reported medicated sex were more likely to engage in a cluster of other behaviors — smoking, higher alcohol consumption, and recreational drug use. They were also more likely to report unsafe sex (two or more partners without condom use in the past year) and, among men, to have met partners online or paid for sex.

This association between medicated sex and risk-taking persisted even after controlling for same-sex behavior and ED, suggesting a deeper behavioral or psychological link.

The Role of Erectile Dysfunction

Among men, 7.2% reported medicated sex in the past year, but this figure soared to 28.4% among those with erectile difficulties. Yet only 13% of men reported ED, meaning that roughly half of all medicated sex occurred among men without erectile dysfunction.

This is perhaps the most striking finding of the study: pharmacologic enhancement is not merely compensatory, but increasingly augmentative — used by men who function well physiologically but seek psychological assurance or superior performance.

The Psychology of Medicated Desire

The association between medicated sex and both high sexual activity and low interest in sex among men without ED presents a paradox. How can men be both highly active and disinterested? The answer, as the authors suggest, lies in sexual confidence.

Research indicates that some men, even those without clinical dysfunction, use sildenafil as a kind of “erectile insurance” — a way to guarantee performance and avoid anxiety-induced failure. The pill becomes a psychological safety net, a pharmacologic proxy for confidence.

However, this reassurance can carry a cost. Studies have shown that recreational use of PDE5 inhibitors may erode natural erectile confidence, creating dependence not on the molecule, but on the belief that one cannot perform without it. Thus, the pursuit of “perfection” in sexual performance can paradoxically diminish genuine self-assurance — a subtle iatrogenic effect of the pharmacological age.

The Women Factor: Absence, Inequality, and Curiosity

That only 1.9% of women reported medicated sex might seem negligible, but it raises important questions about gender disparity in sexual medicine. While male pharmacotherapies for performance abound, female equivalents remain limited by biology, risk, and cultural taboos.

Even where medications exist — testosterone for hypoactive sexual desire or the controversial flibanserin (“Addyi”) for premenopausal women — uptake has been modest. Beyond pharmacology, the social acceptability of women medicating for pleasure or desire remains fraught with stigma.

The Natsal data thus highlight a pharmacological gender gap: men seek enhancement openly; women, when they do, navigate a landscape of medical skepticism and cultural restraint.

Medicated Sex and Risk: Beyond the Usual Suspects

A notable contribution of the Natsal-3 analysis is its demonstration that the link between medicated sex and risky sexual behavior extends beyond high-risk groups.

Previous research had focused on men who have sex with men (MSM), where combinations of PDE5 inhibitors, stimulants, and “chemsex” practices were well documented. The British data show that even among heterosexual men and women, use of sexual performance drugs correlates with behaviors such as multiple partnerships, condomless sex, and recent sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Indeed, over 20% of men diagnosed with an STI in the past year reported using sexual performance medication — a figure that underscores the potential public health implications.

This finding challenges clinicians to expand their discussions about safe sex. Conversations about sexual risk reduction should not be confined to those seeking HIV testing or PrEP, but also include patients who view pharmacologic enhancement as a normal component of their sexual life.

The Informal Market: Convenience at a Cost

As PDE5 inhibitors became more accessible — first via online pharmacies, later through over-the-counter sales in the UK — the boundary between medical supervision and self-medication blurred.

While increased accessibility may reduce embarrassment and expand treatment, it also introduces risks:

- Drug interactions, especially with nitrates and protease inhibitors;

- Counterfeit products, a growing online problem;

- Missed opportunities for physicians to identify underlying vascular or psychological conditions.

Moreover, informal users bypass critical conversations about dosage, contraindications, and expectations. The irony is clear: a medication originally designed to improve health-related quality of life may, when unsupervised, compromise it.

Cultural Reflections: When Sex Becomes a Performance

The proliferation of performance-enhancing drugs reveals something profound about contemporary sexual culture. We live in an era of medicalized intimacy, where the spontaneous has been replaced by the optimized, and satisfaction is measured in minutes of firmness rather than emotional connection.

The Natsal-3 findings reinforce this cultural trend: pharmacology has become not only a medical solution but a social instrument. The expectation that sex must always be “perfect” — powerful, enduring, and repeatable — feeds a market that promises precisely that.

Critics have argued that this medicalization of sex risks pathologizing normal variation and amplifying dissatisfaction. When every deviation from “ideal performance” is framed as dysfunction, both medicine and marketing profit — but human intimacy becomes increasingly commodified.

Clinical Implications: What Physicians Should Know

For healthcare providers, the data from Natsal-3 serve as both a warning and an opportunity. Primary care physicians, sexual health specialists, and even pharmacists are likely to encounter patients using or considering sexual performance medication — often without having disclosed it.

Key takeaways include:

- Screening for unsupervised use: Around 4% of sexually active men without ED reported using medication. These individuals may require counseling about potential drug interactions and realistic expectations.

- Patient education: Clinicians should discuss both physical and psychological aspects — reminding patients that performance drugs amplify physiological response but do not create desire or intimacy.

- Partner communication: Medication affects not only the individual but the couple dynamic. Open discussions about timing, pressure, and expectations can prevent relational strain.

- Broader health insight: ED is often an early indicator of cardiovascular disease; thus, its appearance — even if masked by medication — warrants cardiovascular assessment.

In short, the medical management of medicated sex extends beyond the prescription pad. It requires empathy, dialogue, and an understanding of the social context in which these drugs are used.

The Broader Picture: From Population Data to Policy

The prevalence of medicated sex in Britain — roughly one in eight men and one in fifty women — might appear modest, but its implications are considerable. As medications become easier to obtain without prescription, their social footprint will expand.

Public health initiatives should address not only the risks of unsupervised pharmacologic use but also the expectations that drive it. Sexual confidence, relational satisfaction, and self-perception are as critical to well-being as physiological function.

Educational campaigns could help demystify sexual function, destigmatize dysfunction, and emphasize that healthy sex need not be “medicated sex.” At the same time, healthcare professionals must recognize that for many individuals, these drugs provide genuine relief and renewed confidence — and thus deserve an informed, nonjudgmental approach.

Conclusion: The Pill and the Paradox

The Natsal-3 data reveal a Britain where pharmacology and sexuality are quietly intertwined. For some, medication restores lost function; for others, it offers psychological insurance or recreational thrill. The line between therapy and enhancement has blurred — and perhaps that is the defining feature of our era.

Yet the central paradox remains: in pursuing confidence through chemistry, we may be losing faith in our own biology. As the authors wisely note, the medicalization of sex has made “perfect” performance both an aspiration and a burden.

Medicine can assist in sexual well-being — but it cannot substitute for trust, intimacy, or self-acceptance. Perhaps the ultimate goal of sexual medicine should be not just harder erections or prolonged desire, but the confidence to know that imperfection is human, and intimacy is not measured in milligrams.

FAQ: Medicated Sex — What You Need to Know

1. How common is medicated sex in Britain?

Approximately 13% of men and 2% of women have used medication to enhance sexual performance. Among sexually active men, about 7% reported such use in the past year — half of whom did not have erectile dysfunction.

2. Is medicated sex associated with risky behavior?

Yes. Men and women who use performance-enhancing medication are more likely to report multiple sexual partners, condomless sex, and recent STIs — even after controlling for same-sex activity and erectile dysfunction.

3. Should people without erectile dysfunction use these medications?

Medically, no. While occasional use may seem harmless, habitual recreational use can foster dependence, reduce natural confidence, and obscure underlying health issues. Professional consultation ensures safe, effective, and psychologically balanced treatment.