Introduction

Female sexual dysfunction (FSD) is a broad, multifaceted condition that challenges both clinicians and patients. It is not a singular disease but rather a constellation of disorders encompassing reduced desire, impaired arousal, orgasmic difficulties, and pain. Unlike male sexual dysfunction, which is often approached with pharmacological directness—think sildenafil for erectile dysfunction—female dysfunction is entangled in a far more intricate web of physiology, psychology, and cultural context.

One particularly well-defined subset, hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD), has become the focus of pharmacological innovation and regulatory debate. The disorder is characterized by persistent low sexual desire causing personal distress, in the absence of other medical or psychiatric explanations. While non-pharmacologic interventions such as counseling and lifestyle modification remain fundamental, the quest for a pharmacological solution has been persistent.

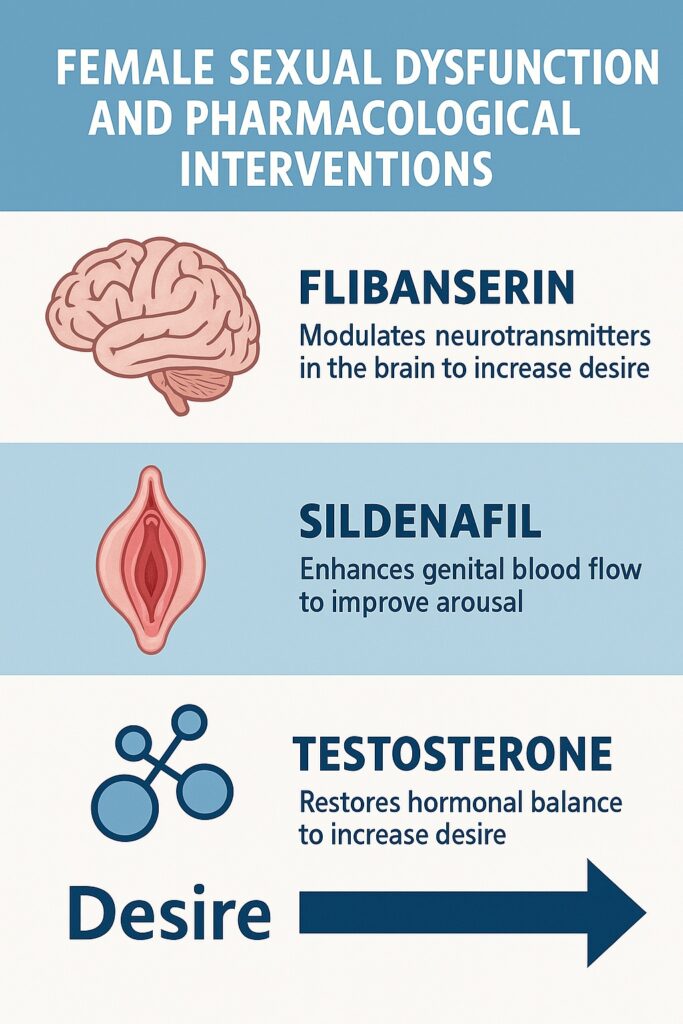

In recent years, three therapeutic agents—flibanserin, sildenafil, and testosterone—have been studied for their potential roles in addressing female sexual dysfunction. Each represents a different mechanistic strategy: modulation of central neurotransmitters, enhancement of genital hemodynamics, and hormonal supplementation. Together, they illustrate both the promise and the limitations of pharmacotherapy in this complex field.

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder: A Clinical Overview

HSDD has long been underdiagnosed and undertreated, in part because women’s sexual health is frequently overshadowed by cultural silence. The prevalence is not trivial; estimates suggest that up to 10–15% of premenopausal women meet criteria for HSDD, with higher figures among postmenopausal women. Yet the diagnosis remains nuanced.

Mechanistically, sexual desire is mediated by a delicate balance of excitatory and inhibitory pathways in the brain. Dopamine and norepinephrine drive excitatory signals, while serotonin often exerts inhibitory control. Beyond neurotransmitters, endocrine factors—particularly androgens—contribute to libido. External elements such as relationship quality, stress, and comorbid depression further complicate the clinical picture.

Diagnostic frameworks emphasize not only reduced sexual thoughts or interest but also associated distress. This distinction is critical: not all low desire is pathological, and pathologizing normal variations risks medicalizing human diversity. Still, for those experiencing genuine dysfunction, the condition can be profoundly disruptive to quality of life, self-image, and relationships.

Flibanserin: The First FDA-Approved Drug for HSDD

Mechanism of Action

Flibanserin represents the first centrally acting agent specifically approved for HSDD in premenopausal women. Unlike sildenafil, which operates peripherally, flibanserin acts on the brain’s neurotransmitter systems. It functions as a 5-HT1A agonist and 5-HT2A antagonist, effectively reducing inhibitory serotonergic tone while enhancing dopaminergic and noradrenergic activity. The result is an attempt to shift the neurochemical balance toward increased sexual desire.

Clinical Efficacy

Clinical trials demonstrated modest but statistically significant benefits. Women treated with flibanserin reported increases in the number of satisfying sexual events (SSEs) per month and improvements in validated desire scores. However, the absolute differences compared to placebo were small—sometimes described as less than one additional satisfying sexual event per month. This has fueled debate about whether the therapeutic effect justifies its use.

Safety and Controversies

The drug is not without baggage. Flibanserin must be taken daily, rather than on demand, and is associated with side effects such as dizziness, somnolence, and hypotension. Importantly, concurrent alcohol consumption can provoke severe hypotension and syncope, leading to a boxed FDA warning. Critics have argued that the modest efficacy combined with these safety concerns makes the drug less than ideal. Supporters counter that, for a condition with few therapeutic options, even incremental benefits are meaningful.

The approval of flibanserin also sparked broader discourse on gender equity in sexual medicine. Advocates emphasized that while men had numerous pharmacological options for sexual dysfunction, women had none until flibanserin. Its approval, therefore, represented not just a therapeutic milestone but also a symbolic correction of imbalance.

Sildenafil: Repurposing a Male Icon for Female Dysfunction

Rationale for Use in Women

Sildenafil citrate, a PDE5 inhibitor originally developed for angina and famously repurposed for erectile dysfunction, enhances genital blood flow by amplifying nitric oxide–cGMP signaling. Given that arousal disorders in women may stem from inadequate genital vasocongestion, sildenafil seemed a logical candidate for translation to female sexual dysfunction.

Evidence from Clinical Trials

Studies have explored sildenafil in women with arousal disorders, particularly those with comorbid conditions such as antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction. Results have been mixed. Some trials demonstrated improvements in genital blood flow, lubrication, and subjective arousal, especially in women without hormonal deficiencies. Others reported minimal or no difference compared to placebo, underscoring the complexity of female sexual response where central desire cannot always be rekindled by peripheral blood flow alone.

A particularly intriguing subset includes postmenopausal women. In these patients, vascular changes, vaginal atrophy, and endothelial dysfunction contribute to arousal difficulties. Sildenafil showed some benefit in improving clitoral and vaginal hemodynamics, but its impact on global sexual satisfaction was inconsistent.

Limitations and Risks

Sildenafil’s application in women is constrained by the same contraindications observed in men—most notably, concomitant nitrate use and cardiovascular instability. Side effects such as headache and flushing are common, and in women, the absence of robust efficacy data has limited regulatory enthusiasm. Unlike flibanserin, sildenafil has not received FDA approval for female dysfunction, and its role remains exploratory.

Testosterone: Revisiting the Hormonal Basis of Desire

Physiological Underpinnings

While often thought of as the quintessential male hormone, testosterone is also critical in women. Produced by the ovaries and adrenal glands, it contributes to libido, energy, and mood. Declining levels with age, oophorectomy, or chronic illness have been associated with reduced sexual desire.

Clinical Evidence

Multiple trials have tested testosterone supplementation in women, typically through transdermal patches or gels. Results consistently show improvements in desire, arousal, and frequency of satisfying sexual activity, particularly in postmenopausal women with low baseline androgen levels. Combination therapy with estrogen appears to amplify benefits, suggesting synergistic hormonal effects.

Despite these encouraging findings, testosterone therapy for women remains controversial. Regulatory agencies, including the FDA, have been reluctant to approve formulations specifically for female sexual dysfunction, citing concerns about long-term safety and potential androgenic effects. Documented side effects include acne, hirsutism, voice deepening, and lipid alterations.

Ethical and Practical Considerations

Prescribing testosterone to women raises ethical and clinical challenges. Without approved formulations, clinicians often resort to off-label prescribing of male formulations at reduced doses, introducing variability in efficacy and safety. Moreover, the line between physiological supplementation and performance enhancement is blurry, adding layers of societal debate.

Comparative Insights: Three Strategies, No Magic Bullet

The juxtaposition of flibanserin, sildenafil, and testosterone highlights the multidimensional nature of female sexual function. Each drug targets a different node in the complex network of desire and arousal:

- Flibanserin modifies central neurotransmitter balance.

- Sildenafil enhances genital hemodynamics.

- Testosterone restores hormonal milieu.

And yet, none of these agents offers a universal solution. Flibanserin’s modest efficacy is tempered by side effects. Sildenafil’s vascular benefits do not consistently translate into improved satisfaction. Testosterone, while promising, is shadowed by safety concerns and regulatory reluctance.

This lack of a “magic bullet” is not a failure of pharmacology but rather a reminder that female sexual dysfunction cannot be reduced to a single pathway. Human sexuality is as much psychological and relational as it is biochemical. Drugs may nudge biology, but they cannot replace intimacy, communication, or emotional health.

Clinical Challenges and Future Directions

Several challenges complicate the pharmacological management of female sexual dysfunction:

First, the heterogeneity of FSD means that a treatment effective in one subgroup may be useless in another. A woman with HSDD rooted in neurotransmitter imbalance may benefit from flibanserin, while another with vascular insufficiency might respond better to sildenafil. Personalized medicine, guided by biomarkers and detailed clinical evaluation, remains an unmet need.

Second, safety and tolerability are paramount. Any drug for sexual dysfunction must not only work but also be safe for long-term use. Women with chronic comorbidities—hypertension, diabetes, depression—constitute a large portion of the affected population, and their polypharmacy complicates treatment.

Third, regulatory skepticism persists. The modest efficacy of these agents relative to placebo has left agencies cautious. At the same time, the societal discourse around female sexuality adds political dimensions to scientific debates.

Looking ahead, combination therapies—pairing hormonal supplementation with central agents, or integrating pharmacology with psychosexual counseling—may offer a way forward. Research into newer targets, including melanocortin receptor agonists and novel serotonergic modulators, continues, albeit slowly.

Conclusion

Female sexual dysfunction, particularly hypoactive sexual desire disorder, remains a pressing yet under-addressed domain of medicine. Pharmacological approaches, while imperfect, represent important steps in acknowledging women’s sexual health as a legitimate medical concern.

Flibanserin, as the first FDA-approved drug for HSDD, provides proof of concept but limited efficacy. Sildenafil illustrates how lessons from male dysfunction do not always translate seamlessly to women, though vascular support may help specific subgroups. Testosterone, rooted in physiology, demonstrates clear potential but awaits safer, standardized formulations.

Ultimately, these agents highlight that there is no singular fix for FSD. Sexuality is not purely chemical, and while drugs can support physiology, they must be integrated into a holistic framework that includes psychological, relational, and cultural dimensions. For clinicians and patients alike, the journey involves setting realistic expectations, balancing risks and benefits, and recognizing that pharmacology is a tool—not a cure-all—in the broader canvas of women’s sexual health.

FAQ

1. Is flibanserin a “female Viagra”?

Not exactly. While sildenafil (Viagra) acts peripherally to improve blood flow, flibanserin acts centrally on brain neurotransmitters to increase desire. The mechanisms and patient populations differ significantly.

2. Can women safely take testosterone for low sexual desire?

Evidence suggests benefits, particularly in postmenopausal women with low androgen levels, but concerns about long-term safety and side effects remain. No FDA-approved formulation exists for this indication.

3. Does sildenafil work for female sexual dysfunction?

Sildenafil can improve genital blood flow and may help some women with arousal disorders, especially those with antidepressant-induced dysfunction. However, its overall impact on sexual satisfaction is inconsistent, and it is not formally approved for women.