Erectile dysfunction (ED) is often framed as a quality-of-life issue—awkward to discuss, easy to postpone, and, regrettably, frequently labeled “just stress.” That framing is dangerously incomplete. In many men, ED is an early clinical manifestation of systemic vascular disease, sometimes preceding overt coronary symptoms by years. When a patient reports persistent difficulties achieving or maintaining erections, the cardiovascular system deserves center stage. The penis, with its exquisitely small arteries and relentless demand for endothelial finesse, is frequently the first vascular bed to complain when atherosclerosis is gathering momentum.

This article explains why ED is not merely coincident with myocardial infarction (MI) risk but biologically implicated as an actionable sentinel. We will connect basic vascular biology to bedside decision-making, translate mechanisms into pragmatic screening, and offer a concise approach to prevention and therapy. The aim is simple: help clinicians and informed readers use ED as an early opportunity to prevent heart attacks rather than as a late clue revisited after the fact.

Yes, ED can be multifactorial—psychogenic, neurogenic, hormonal, and iatrogenic contributors are real—but even then, the vascular thread is common and clinically fertile. The task is not to medicalize sexuality; it is to recognize that the arteries of sexual function are the same arteries entrusted with keeping myocardium alive. When one network fails, assume the rest is at risk until proven otherwise.

The Vascular Biology Linking ED and Coronary Disease

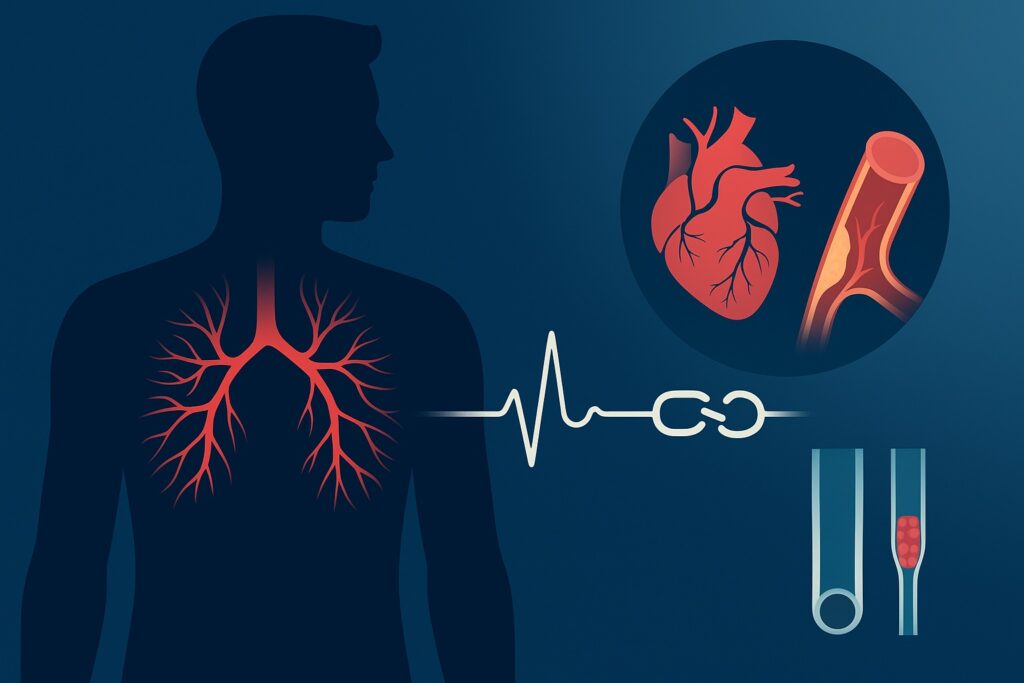

At the center of both ED and coronary artery disease (CAD) lies endothelial dysfunction. The healthy endothelium regulates vascular tone through nitric oxide (NO) production, suppresses inflammation, and prevents thrombosis. Hyperglycemia, smoking, dyslipidemia, and hypertension sabotage these defenses, reducing NO bioavailability and inviting oxidative stress. In the penis, where rapid, high-flow vasodilation is essential, even modest endothelial impairment degrades performance. In the coronaries, the same impairment sets the stage for plaque formation and instability.

The “artery size hypothesis” offers an intuitive clinical bridge. Given the same systemic atherosclerotic burden, smaller arteries will manifest flow-limiting disease earlier than larger arteries. Penile arteries are roughly 1–2 mm in diameter; coronary arteries are about 3–4 mm. When plaques, stiffening, and vasomotor dysregulation advance system-wide, erectile function frequently deteriorates before exertional angina ever enters the conversation. What looks like a bedroom problem may, in vascular terms, be a preview of coronary trouble.

Beyond the macrocirculation, microvascular dysfunction is highly relevant. Many men with ED and normal penile Doppler studies still harbor impaired endothelial signaling and dysfunctional smooth muscle relaxation. Similarly, a subset of patients with “normal” coronary angiograms exhibit microvascular angina or ischemia with non-obstructive coronary arteries (INOCA). The shared pattern is a global loss of vasodilatory reserve, often accompanied by low-grade inflammation and heightened sympathetic tone. ED becomes a clinical tip-off to probe deeper.

How Erectile Dysfunction Signals Higher Cardiac Risk

Epidemiologic studies consistently show that men with ED have higher rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), even after adjusting for age, smoking, diabetes, and other usual suspects. The gradient tracks with severity: more severe or persistent ED corresponds to higher event risk. Early-onset ED—particularly before age 50—carries a stronger signal for occult cardiometabolic disease. This is not guilt by association; it is a reflection of shared mechanisms manifesting earlier in the smallest vessels.

The temporal relationship also matters. In many cohorts, ED emerges years before first cardiovascular events. That lead time is an opportunity. The practical implication is to treat persistent ED as you would new exertional dyspnea or atypical chest discomfort: as a symptom that warrants a structured risk assessment, not as a nuisance to be managed in isolation. If anything, ED is a more tolerable alert than angina; we should not ignore the polite warning and wait for the siren.

Distinguishing psychogenic from organic ED remains important, but the lines blur. Anxiety and depression can impair sexual performance, yet both also correlate with systemic inflammation, poor sleep, and unhealthy behaviors that worsen vascular health. Conversely, organic vascular ED often worsens performance anxiety—a rather unhelpful virtuous cycle. Clinical judgment must acknowledge that even when psychogenic factors dominate the narrative, cardiometabolic screening is still wise if risk factors are present.

Turning a Symptom into a Cardiovascular Evaluation

When a patient presents with ED, the initial history should cast a wide cardiometabolic net. Clarify onset, severity, and consistency across settings; ask about morning erections, libido, and any relation to exertion or emotional stress. Then immediately pivot to classic vascular risk questions: smoking status, family history of premature CAD, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes or prediabetes, sleep apnea symptoms, physical activity, and diet. Medication review is crucial—beta-blockers, thiazides, certain SSRIs/SNRIs, and finasteride can contribute, though they seldom explain the entire picture.

Physical examination ought to be as routine as it is revealing. Measure blood pressure properly (including orthostatics if dizziness is reported), assess BMI and waist circumference, palpate peripheral pulses, and look for stigmata of endocrinopathies. Simple bedside clues—xanthelasma, arcus, diminished dorsalis pedis pulses—are not diagnostic but should heighten suspicion for generalized atherosclerosis. For many men, this is the first time in years someone has combined sexual health with a blood pressure cuff and a tape measure.

Laboratory testing can be both targeted and efficient. A reasonable baseline panel includes fasting lipids, fasting glucose or HbA1c, serum creatinine with eGFR, and morning total testosterone if there is low libido, fatigue, or other hypogonadal features. Thyroid-stimulating hormone can be helpful when symptoms suggest thyroid disease. These modest tests often unmask silent diabetes, atherogenic dyslipidemia, or chronic kidney disease—all conditions that accelerate both ED and coronary events.

When to Escalate: Red Flags and Structured Risk

Symptoms drive urgency. ED accompanied by exertional chest pressure, breathlessness, palpitations, or syncope should prompt immediate cardiac evaluation, not sexual-function triage. Even in the absence of active symptoms, risk stratification is warranted. In primary care, formal calculators (e.g., 10-year ASCVD risk) provide a baseline, but ED—especially when persistent and unexplained—should be treated as a risk enhancer that nudges thresholds for preventive therapy.

Noninvasive testing is most helpful when it changes management. A resting ECG is low-cost and occasionally revealing, but its sensitivity for occult CAD is limited. Exercise treadmill testing can unmask functional ischemia in suitable patients with intermediate pretest probability who can exercise and have an interpretable ECG. For others, coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring offers a quick portrait of plaque burden; a CAC score above zero, particularly at younger ages, meaningfully reclassifies risk and strengthens the argument for aggressive prevention. The goal is not to scan everyone with ED; it is to use ED as the nudge that justifies better risk definition.

Urologic testing has a role, but keep the hierarchy clear. Penile Doppler ultrasound, nocturnal tumescence testing, and endocrine panels help phenotype ED for targeted therapy. They do not substitute for cardiovascular evaluation. If a man has significant ED of vascular flavor, treat cardiovascular risk as a parallel priority. When in doubt, a collegial referral to cardiology can ensure that the prevention window is not missed while local management of sexual function proceeds.

Seek urgent evaluation if ED occurs alongside:

- New chest pain, chest pressure, or unexplained breathlessness during activity or at rest

- Palpitations with dizziness or syncope, or any neurological deficit

- Abrupt decline in exercise tolerance, edema, or orthopnea in a patient with multiple risk factors

Biomarkers, Hormones, and the “Hidden Drivers”

The hormone discussion around ED is often simplified to testosterone, but the cardiometabolic story is broader. Low testosterone (particularly when clearly symptomatic and confirmed on repeat morning testing) correlates with visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, and adverse lipid profiles. Whether low testosterone is a cause, consequence, or both is less important clinically than recognizing it as a marker of cardiometabolic strain. If replacement is considered, it must be individualized, with attention to hematocrit, prostate health, fertility goals, and shared decision-making.

Inflammatory markers such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) reflect systemic vascular risk. Elevated levels, while nonspecific, often track with insulin resistance, sleep apnea, and central obesity. They can support a prevention-first conversation even when standard risk calculators feel falsely reassuring in a 45-year-old with “borderline” lipids and stubborn ED. This is an area for nuance rather than checklists: a mildly elevated hs-CRP is not destiny, but it is a straw on the camel’s back that should not be ignored.

Renal function and microalbuminuria are underused in this context. Chronic kidney disease amplifies atherothrombotic risk and accelerates endothelial dysfunction. When ED accompanies declining eGFR or albuminuria, aggressive blood pressure control, renin–angiotensin system blockade when appropriate, and lipid lowering are not optional extras—they are the main event that will do more for the patient’s heart and erections than any single urologic intervention.

Treatment That Protects the Heart and the Patient

Lifestyle therapy is not a moral lecture; it is physiology in action. Weight reduction in central obesity improves endothelial function, restores NO signaling, and reduces systemic inflammation. Regular aerobic activity and modest resistance training enhance insulin sensitivity and autonomic balance. Nutritional patterns rich in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and unsaturated fats support vascular health, while high-sodium, refined sugar, and trans-fat-heavy diets do the opposite. These are not platitudes; they are the lowest-risk, highest-value interventions for both ED and MI prevention.

Pharmacotherapy should follow contemporary cardiovascular prevention principles while respecting sexual function. Statins lower LDL-C and reduce events; they also may improve endothelial performance over time. Concerns about statin-related ED are frequently overstated; when ED worsens after statin initiation, look for other variables and consider a switch rather than abandonment. Blood pressure agents can be tailored: ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and calcium-channel blockers are generally neutral to favorable for erectile function, while older, non-selective beta-blockers and high-dose thiazides can be problematic; modern, vasodilating beta-blockers are often better tolerated.

Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors (PDE5i) are effective for many men and, reassuringly, safe for most patients with stable cardiovascular disease. The absolute contraindication is concomitant nitrate therapy, which can cause profound hypotension. Caution is also warranted with recent MI, unstable angina, advanced heart failure, or complex polypharmacy. Framed correctly, PDE5i do more than restore erections—they amplify NO signaling and can serve as a tangible reward for adherence to broader preventive care. The art lies in timing and in reminding patients that a pill that enables sexual activity does not neutralize the underlying vascular risks that created the problem.

Using ED as a “Window of Opportunity” for Prevention

The years between first persistent ED and first coronary event are a gift. They allow clinicians to convert a sensitive conversation into a prevention plan that feels relevant and motivating. Men who might disengage from abstract risk percentages will often engage when the objective is to protect both the heart and sexual health. This is not manipulation; it is good medicine aligned with patient priorities.

Sleep deserves an explicit note. Obstructive sleep apnea is a potent destabilizer of autonomic tone, blood pressure, and endothelial function. It is prevalent in men with resistant hypertension, obesity, and ED. Screening with validated questionnaires, followed by appropriate testing and treatment, can yield meaningful improvements in energy, blood pressure control, and sexual performance. The same holds for alcohol overuse and nicotine in all forms—two reliable saboteurs of endothelial integrity.

Psychological health is both contributor and consequence. Depression and chronic stress shift hormonal and autonomic balance away from sexual function and toward survival mode; they also erode adherence to diet, activity, and medication. A compassionate approach that normalizes mental health care is integral, not ancillary, to preventing MI in men presenting with ED. It is hard to exercise, sleep, and take lipid-lowering therapy when mood is underwater; treating the mind frees the body to cooperate.

Special Populations Where the Signal Is Stronger

In diabetes, the ED–MI connection is amplified and accelerated. Glycation end-products, microvascular damage, and autonomic neuropathy converge to undermine erectile function early and robustly. For a middle-aged man with diabetes, worsening ED is akin to a flashing dashboard light for silent ischemia and diffuse atherosclerosis. Here, intensive risk-factor control—LDL-C lowering to guideline targets, blood pressure optimization, glucose control with agents that also confer cardiovascular benefit—has outsized impact. Sexual function often improves as the vasculature recovers, which is a useful barometer to share with patients.

Younger men with ED deserve special attention. A 38-year-old with persistent, unexplained ED is not “too young for heart disease.” He is precisely the patient in whom subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiometabolic dysfunction hide in plain sight. Waiting for a borderline 10-year risk estimate to justify action misses the point; a lifetime risk framework and selective use of CAC scoring or exercise testing can bring clarity and momentum to prevention.

After prostate cancer therapy—particularly radical prostatectomy or pelvic radiation—ED is common, and mechanisms include nerve injury and vascular changes. The presence of post-treatment ED does not negate cardiovascular evaluation; in fact, androgen deprivation therapy can worsen metabolic risk. Distinguishing iatrogenic from vascular ED is helpful for expectations and therapy, but the cardiometabolic screen should be routine in survivorship care.

Integrating ED into Everyday Clinical Workflow

To make ED a reliable harbinger rather than a retrospective clue, we need a simple, repeatable workflow. In primary care and urology settings, that means embedding cardiovascular screening triggers into ED visits. It is neither time-consuming nor exotic; it is a disciplined checklist applied consistently. Clinicians should also be explicit with patients: “We are checking your heart risk because erectile issues often precede heart problems. Fixing both is the goal.”

A practical approach starts with risk history, proceeds to examination and labs, and then uses a small set of tests (exercise testing or CAC) in selected patients to refine the plan. Shared decision-making ties it together: thresholds for statin therapy, blood pressure agents, glucose-lowering medications with cardiovascular benefit, and PDE5i use are best decided with the patient’s values in view. The unglamorous secret is follow-up—tracking blood pressure, LDL-C, A1c, weight, and functional capacity—because vascular health improves on the scale of months to years, not days.

Health systems can help by creating “ED-cardio bundles” that pre-order lipids, A1c, creatinine, and blood pressure monitoring with the first ED consult, and by standardizing referral pathways for intermediate-risk patients. When these pieces are in place, ED consults become prevention clinics in disguise. Few clinicians complain when their busiest clinics also become their most effective.

A streamlined care pathway for men presenting with ED:

- Screen for vascular risk (history, BP, BMI/waist, lipids, glucose/HbA1c, creatinine; consider morning testosterone if low libido).

- Stratify cardiac risk; consider ECG, exercise testing, or CAC in selected patients to reclassify risk and guide intensity of prevention.

- Initiate lifestyle and pharmacologic prevention (statin, BP optimization, diabetes therapy with CV benefit); use PDE5 inhibitors when appropriate and avoid nitrates.

Pitfalls, Myths, and How to Avoid Missing the Signal

Not every case of ED predicts an impending MI. Temporary performance issues tied to acute stress, relationship conflict, or medication changes happen. The pitfall is using that possibility as an excuse to skip cardiovascular screening altogether. A balanced approach acknowledges psychogenic contributors while still checking the cardiometabolic basics, especially when ED is persistent, progressive, or accompanied by risk factors.

Overtesting is the mirror-image mistake. Ordering advanced imaging for every man with ED leads to incidental findings, cost, and confusion. The smart path is to reserve exercise testing or CAC for those whose pretest probability is intermediate or whose results will change therapy. The objective is not to have the most data; it is to have the right data to justify the most effective prevention.

Finally, myths about ED therapies can derail good care. PDE5 inhibitors do not “strain the heart” in stable patients; they reduce afterload and improve endothelial signaling. Conversely, nitrates do not become safe just because the ED is severe. And while testosterone therapy can help carefully selected hypogonadal men, it is not a universal fix and must never distract from LDL-C lowering, blood pressure control, and smoking cessation—the unglamorous champions of both cardiac and erectile outcomes.

Conclusion: Hear the Whisper Before the Shout

ED is often the quiet voice of the vascular system saying, “Something is off.” Myocardial infarction is the shout. Our job is to listen to the whisper and act decisively. Treating ED as a harbinger of MI means using it to trigger cardiometabolic screening, to personalize prevention, and to motivate sustainable change. Done well, this approach restores sexual function, reduces cardiac events, and spares patients and families the regret of seeing the pattern only in hindsight. The irony is gentle but firm: the path to a healthier heart sometimes begins with an honest conversation about sex.

FAQ: Quick Answers to Common Questions

Does having erectile dysfunction mean I will have a heart attack?

No. ED does not guarantee a heart attack, but it is a meaningful risk signal—especially when persistent, early-onset, or accompanied by other risk factors. It warrants a cardiovascular evaluation to identify and treat modifiable risks before an event occurs. Think of ED as an early alert that allows for prevention, not as a prophecy.

Are ED medications safe if I have heart disease?

For most patients with stable cardiovascular disease, PDE5 inhibitors are safe and effective. The critical exception is concurrent nitrate therapy (for angina), which is contraindicated due to the risk of severe hypotension. If you have unstable symptoms, recent MI, or complex heart failure, you should be evaluated before resuming sexual activity or starting ED therapy.

What practical steps should I take after new-onset ED?

Seek a focused cardiovascular assessment: blood pressure, lipids, glucose/HbA1c, kidney function, and a review of medications. Prioritize lifestyle changes—weight management, regular physical activity, improved diet, sleep optimization, and smoking cessation. Discuss with your clinician whether additional testing (exercise testing or calcium scoring) could refine your risk and whether preventive medications (statins, antihypertensives, diabetes agents with cardiovascular benefit) and ED-specific therapy are appropriate. If acute chest discomfort, breathlessness, or syncope occurs, seek urgent care immediately.