Introduction

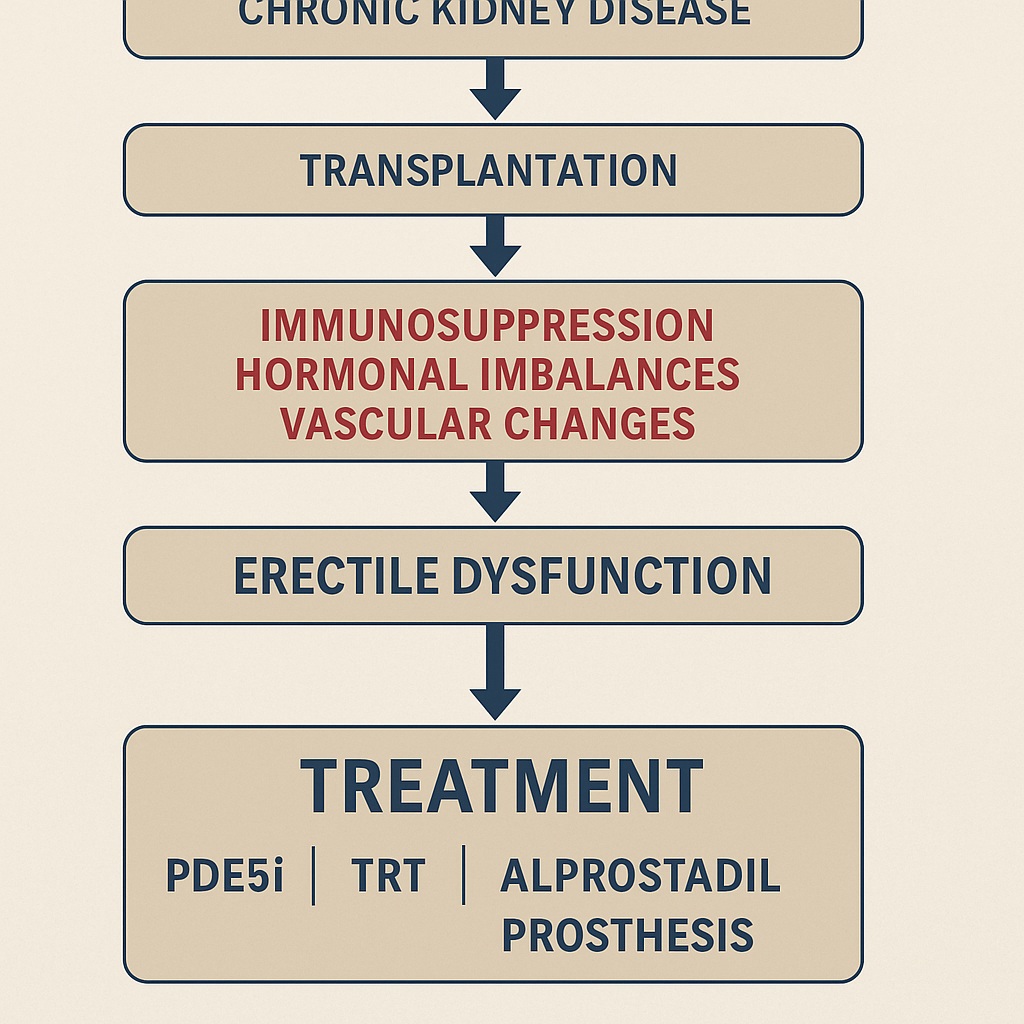

Kidney transplantation remains the gold standard treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), offering superior survival and quality of life compared to dialysis. Yet, behind the celebratory headlines of “graft survival” and “creatinine normalization,” there lies a quieter but equally important story: the persistence of sexual dysfunction. For men, erectile dysfunction (ED) represents one of the most underestimated yet impactful sequelae after transplantation.

While one might assume that restoring renal function would automatically repair the hormonal and vascular disturbances induced by chronic kidney disease (CKD), clinical reality is less forgiving. Data consistently show that nearly six out of ten kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) continue to suffer from ED, a prevalence far exceeding that of the general male population. This residual burden cannot be attributed to one factor alone but reflects a mosaic of endocrine abnormalities, vascular injury, pharmacological side effects, surgical consequences, and psychological dimensions.

This article explores the pathophysiology, risk factors, and therapeutic approaches for ED after kidney transplantation, positioning it as not a marginal issue but a central determinant of post-transplant quality of life.

Why ED Persists after Transplantation

At first glance, transplantation seems like the ultimate reset button: filtration improves, toxins clear, anemia corrects, and hormones stabilize. Unfortunately, decades of uremia leave indelible marks on both systemic and penile physiology.

Persistent hypogonadism is a prime culprit. Many male KTRs exhibit low testosterone despite graft function, in part due to the toxic effects of calcineurin inhibitors on Leydig cells and central hypothalamic–pituitary regulation. Hyperprolactinemia and secondary hyperparathyroidism may also linger, perpetuating hormonal imbalance.

Vascular pathology contributes as well. Uremia causes irreversible endothelial dysfunction, cavernous smooth muscle fibrosis, and microvascular remodeling. Even when creatinine falls, these structural penile changes persist, limiting erectile capacity. To add insult to injury, the surgical act of renal transplantation itself—particularly end-to-end anastomosis of the internal iliac artery—can reduce penile arterial inflow, compromising hemodynamics.

Thus, transplantation may correct biochemical parameters but cannot erase years of cumulative damage nor neutralize new iatrogenic stressors.

Hormonal Dysregulation: The Hypogonadism Puzzle

Testosterone is not merely the hormone of libido; it is a structural custodian of penile tissue integrity. Deficiency leads to apoptosis of smooth muscle cells, altered nitric oxide (NO) signaling, and impaired veno-occlusive function. In KTRs, hypogonadism may be hypergonadotropic (primary Leydig cell failure) or hypogonadotropic (secondary to prolactin excess or HPG suppression).

The persistence of hypogonadism after transplantation remains a paradox. While some studies report partial normalization of testosterone within months, others find continued dysfunction even with well-functioning grafts. Immunosuppressive agents, especially calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids, play a decisive role by exerting toxic effects on Leydig cells and central regulatory axes.

Correcting hypogonadism is therefore not a cosmetic intervention but a cornerstone of ED management. Evidence shows that testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) in KTRs is safe, improves anemia, increases muscle mass, and enhances erectile response—especially when combined with PDE5 inhibitors.

Immunosuppressive Drugs: Friends and Foes

The very drugs that secure graft survival often sabotage sexual health. Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporin A, tacrolimus) are notorious for causing hypertension, diabetes, and endothelial dysfunction—all established ED risk factors. Cyclosporin, in particular, impairs NO-mediated smooth muscle relaxation and promotes fibrosis of the corpora cavernosa.

mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus) further complicate the picture. Their benefits in nephroprotection are offset by gonadotoxicity: decreased sperm count, impaired spermatogenesis, and hypogonadism. The damage, though sometimes reversible, casts a shadow on long-term sexual function.

Glucocorticoids, another cornerstone of immunosuppression, suppress GnRH and LH secretion, reduce testosterone synthesis, and directly trigger Leydig cell apoptosis. Meanwhile, mycophenolate and azathioprine appear less directly harmful to erectile capacity but raise concerns regarding fertility.

The clinical implication is sobering: prolonged immunosuppression carries an inevitable sexual cost, which must be factored into the holistic care of transplant recipients.

Psychological and Social Dimensions

Sexuality is not merely vascular hydraulics and hormonal chemistry. Kidney transplantation, while life-saving, can trigger complex psychological adaptations. Altered body image (surgical scars, changes in weight or muscle mass), fear of graft rejection, and depression contribute to reduced sexual confidence. Anxiety about performance, coupled with pre-existing relationship strains, compounds the risk of ED.

Notably, education and socioeconomic status correlate inversely with ED prevalence in KTRs. Men with limited health literacy may prioritize graft survival over sexual health, underreporting dysfunction and remaining untreated. This silence perpetuates a cycle of frustration, relational discord, and diminished quality of life.

Thus, addressing ED in KTRs requires not only pharmacology but also psychosexual support, counseling, and open communication—areas often neglected in nephrology clinics.

Treatment Strategies

Management of ED in kidney transplant recipients requires nuance: treatments must restore function without compromising graft health or interacting with immunosuppressive regimens.

First-line: PDE5 inhibitors

Sildenafil and vardenafil have demonstrated safety and efficacy in KTRs, without major pharmacokinetic interactions with cyclosporin or tacrolimus. Dosing, however, must be adjusted in severe renal impairment. Tadalafil, given its longer half-life, requires caution in advanced dysfunction but can be effective in moderate cases.

Second-line: Alprostadil

Intracavernous injections or intraurethral suppositories of alprostadil bypass systemic drug–drug interactions and preserve renal safety. They are particularly valuable in patients unresponsive or contraindicated for PDE5 inhibitors.

Third-line: Penile prostheses

For refractory cases, penile prosthesis implantation offers durable results. In transplant recipients, timing is critical: surgery should be delayed until graft stability is ensured, and infection risk minimized.

Emerging options

- Low-intensity shockwave therapy (Li-SWT): early trials suggest endothelial regeneration and neovascularization benefits.

- Endothelial progenitor cells: an experimental frontier aiming to repair microvascular damage.

- Combination therapy: testosterone replacement plus PDE5 inhibitors yields superior outcomes in hypogonadal men.

Ultimately, treatment must be personalized, balancing efficacy with graft preservation and overall metabolic health.

The Importance of Early Detection

ED in KTRs should not be dismissed as a mere inconvenience. It is a clinical red flag for broader endothelial dysfunction, cardiovascular risk, and ongoing hormonal imbalance. Ignoring ED risks missing the opportunity for early intervention in systemic disease.

Routine screening should include:

- Hormonal panel (testosterone, prolactin, LH/FSH)

- Vascular assessment (Doppler ultrasound, endothelial markers)

- Psychosocial evaluation

- Careful drug review to identify modifiable contributors

By systematically addressing ED, clinicians can enhance not only sexual health but also long-term survival and graft function.

Conclusion

Kidney transplantation is a triumph of modern medicine, yet its promise is incomplete if recipients remain trapped in the silent shadow of erectile dysfunction. The high prevalence of ED in this population reflects the cumulative burden of uremia, persistent hormonal imbalance, vascular injury, immunosuppressive toxicity, and psychological stress.

Fortunately, effective therapies exist—from PDE5 inhibitors to testosterone replacement, from alprostadil injections to surgical implants. What is needed is clinical vigilance: proactive screening, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the courage to discuss sexuality openly with patients.

Addressing ED after kidney transplantation is not a luxury. It is a medical responsibility, a quality-of-life imperative, and, perhaps most importantly, a reminder that successful transplantation is not just about survival but about restoring the wholeness of human experience.

FAQ

1. Is erectile dysfunction common after kidney transplantation?

Yes. Despite improved renal function, around 60% of male kidney transplant recipients experience ED due to persistent hormonal, vascular, and psychological factors.

2. Are PDE5 inhibitors safe for transplant patients?

Generally, yes. Sildenafil and vardenafil are safe and effective without significant drug interactions. Tadalafil requires dose adjustment in renal impairment.

3. Can testosterone therapy be used in kidney transplant recipients with ED?

Yes, when hypogonadism is confirmed. Testosterone replacement improves sexual function, anemia, and muscle mass, and can safely be combined with PDE5 inhibitors under medical supervision.