Introduction: Beyond Tremor and Rigidity

For much of medical history, Parkinson’s disease (PD) has been defined by its motor hallmarks—tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. These visible signs are dramatic and diagnostic, but they tell only part of the story. Beneath the surface lies an equally disruptive but far less recognized realm of pathology: autonomic dysfunction.

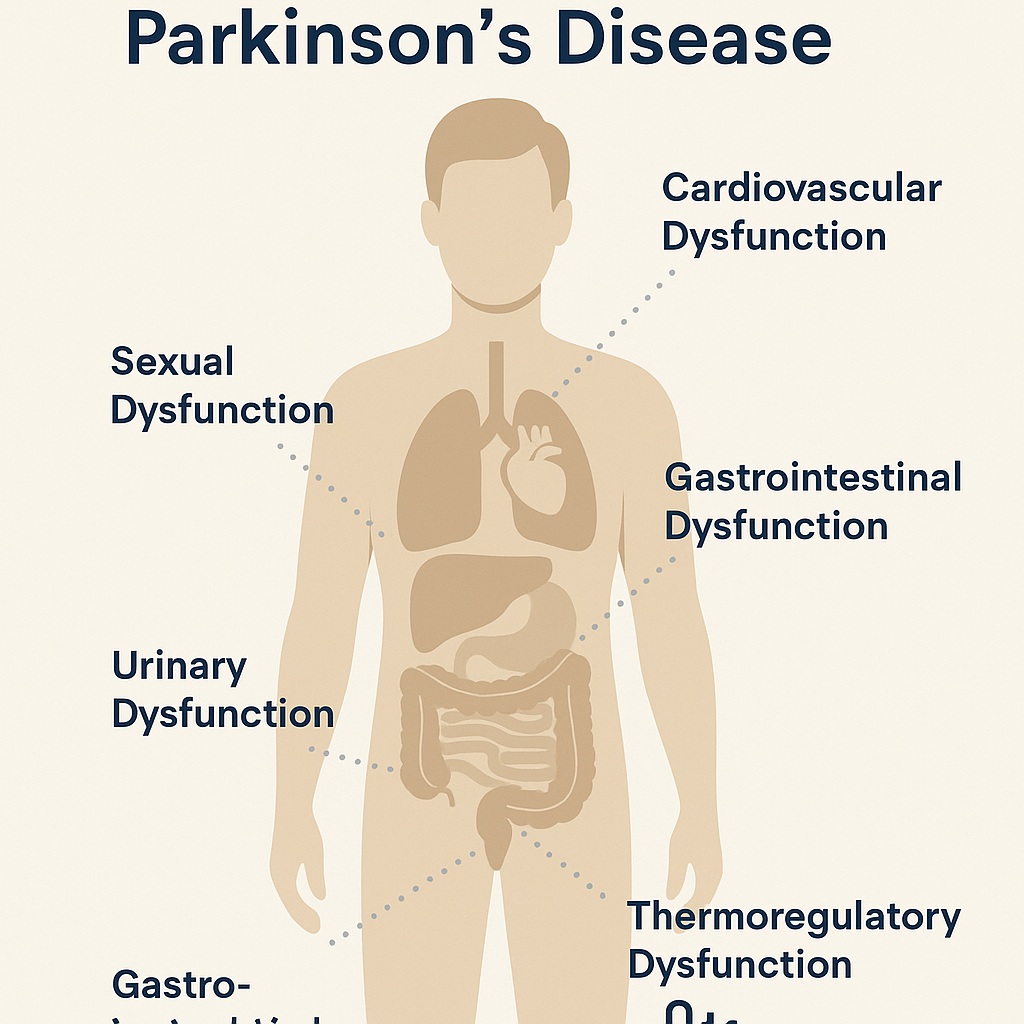

Autonomic disturbances in PD affect almost every involuntary system in the body—from the heart to the gut, the bladder to the sweat glands. The result is a constellation of symptoms that can profoundly reduce quality of life. Indeed, some researchers suggest that autonomic decline predicts faster disease progression and shorter survival.

It is a striking paradox: while clinicians often focus on managing tremor, the patient may be far more troubled by dizziness on standing, constipation, urinary urgency, or unexplained sweating. Understanding these symptoms is therefore not an optional add-on but a central component of comprehensive Parkinson’s care.

The Nervous System’s Invisible Partner: Anatomy of Autonomic Failure

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) orchestrates bodily homeostasis—maintaining blood pressure, heart rate, digestion, and thermoregulation without conscious control. In PD, both sympathetic and parasympathetic branches are affected. Pathology extends from central regions such as the hypothalamus and brainstem to peripheral structures, including cardiac sympathetic fibers and enteric plexuses.

This dual damage explains the sheer breadth of dysfunction. Cardiac sympathetic denervation leads to orthostatic hypotension; loss of parasympathetic tone slows gastrointestinal transit; degeneration of hypothalamic neurons distorts thermoregulation. In short, PD unbalances the delicate seesaw that sustains internal equilibrium.

Cardiovascular Dysfunction: When Blood Pressure Refuses to Cooperate

Orthostatic Hypotension

Perhaps the most clinically important autonomic manifestation of PD is neurogenic orthostatic hypotension (nOH)—a sustained drop in blood pressure upon standing. It arises from failure of baroreflex pathways and insufficient norepinephrine release from postganglionic sympathetic neurons.

Patients may describe transient lightheadedness, blurred vision, “coat-hanger” neck pain, or even sudden syncope. Yet many are asymptomatic, leading to underdiagnosis. Roughly one-third of PD patients experience measurable orthostatic hypotension, even early in disease.

Distinguishing neurogenic from non-neurogenic causes is crucial. In nOH, the heart rate fails to rise appropriately, a reflection of impaired autonomic reflexes. Treatment begins with lifestyle measures—hydration, salt liberalization, compression garments, and head-up sleeping—before progressing to agents such as fludrocortisone, midodrine, or droxidopa. Each has its hazards: supine hypertension, edema, or cognitive side effects may limit tolerance.

Clinically, managing orthostatic hypotension in PD requires balancing opposing dangers: too low a pressure by day invites fainting; too high a pressure by night risks vascular damage. A therapeutic tightrope, indeed.

Supine and Postprandial Hypertension

Ironically, many patients with nOH experience supine hypertension, with elevated blood pressure when lying flat—another consequence of autonomic imbalance. Roughly half of affected individuals show this paradoxical pattern. Nonpharmacologic countermeasures such as elevating the head of the bed are first-line, while short-acting antihypertensives at bedtime (e.g., captopril or clonidine) can be considered.

Postprandial hypotension, meanwhile, lurks after large carbohydrate-rich meals. Avoiding heavy meals and favoring smaller, more frequent portions can prevent postprandial swoons—a practical yet often overlooked intervention.

The Gastrointestinal Tract: The Second Brain’s Slow Descent

The gut-brain axis is more than a metaphor. The enteric nervous system, densely populated with dopaminergic neurons, is often one of the earliest sites of PD pathology. As alpha-synuclein aggregates march down the vagus nerve, the digestive system begins to falter.

Excess Saliva and Dysphagia

Paradoxically, PD patients drool not because they produce too much saliva, but because they swallow too little. Bradykinesia extends to the oropharyngeal muscles, leading to drooling, embarrassment, and aspiration risk. Chewing gum may offer minor reprieve, but modern management relies on botulinum toxin injections into salivary glands, which can dry the mouth without crossing the blood–brain barrier.

Dysphagia, or impaired swallowing, affects up to 80% of patients when objectively tested, even when they are unaware of the problem. This symptom carries serious consequences—malnutrition, aspiration pneumonia, and medication inefficacy. Behavioral therapy and expiratory muscle strength training remain the backbone of treatment, occasionally complemented by surgical or neurostimulatory interventions.

Gastroparesis: The Stomach that Forgot Its Job

Delayed gastric emptying—or gastroparesis—translates to nausea, bloating, and the all-too-familiar “off” episodes after levodopa dosing. The stomach simply refuses to deliver medication to the intestine on time.

The dopamine antagonist metoclopramide, effective in the general population, is contraindicated in PD for obvious reasons. Instead, domperidone—a peripherally acting agent—offers symptom relief and even enhances levodopa absorption, though its cardiac safety remains debated. Other hopefuls, like prucalopride and relamorelin, await further validation.

Constipation and Small Intestinal Dysfunction

Constipation may precede motor symptoms by decades, making it one of PD’s earliest prodromal signs. It stems from sluggish colonic transit and pelvic floor dyssynergia, not mere dietary neglect.

Management starts with fiber, fluids, and osmotic laxatives, then extends to probiotics, secretagogues (lubiprostone, linaclotide), and, in severe cases, botulinum toxin injections for outlet obstruction. Intriguingly, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) affects up to half of PD patients, worsening motor fluctuations by altering levodopa metabolism—a vivid example of gut microbes meddling in neurology.

Urinary Dysfunction: The Bladder’s Rebellion

The micturition reflex depends on inhibitory control from the basal ganglia. In PD, dopaminergic depletion releases the brake, resulting in detrusor overactivity—manifesting as urgency, frequency, and nocturia. Some patients, however, experience the opposite: hesitancy and incomplete emptying due to sphincter bradykinesia or detrusor underactivity.

Nonpharmacologic measures (scheduled voiding, pelvic floor training) should precede pharmacotherapy. Older anticholinergics such as oxybutynin are effective but risky, given their cognitive side effects. Newer agents—darifenacin, solifenacin, trospium, and the β3-agonist mirabegron—offer safer alternatives. For refractory cases, botulinum toxin detrusor injections provide relief, though retention risk looms.

In selected patients, deep brain stimulation (DBS) targeting the subthalamic nucleus has serendipitously improved urinary symptoms, illustrating again the interconnectedness of neural circuits controlling movement and autonomic function.

Sexual Dysfunction: The Unspoken Symptom

Few topics generate more discomfort in the clinic than sexual dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease, yet it affects the majority of patients—men and women alike. In men, erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction dominate; in women, reduced libido and arousal difficulties are common. Depression, fatigue, and altered body image add psychological layers to the physiological ones.

Pharmacologic treatment mirrors that in the general population: PDE5 inhibitors such as sildenafil and tadalafil are safe and effective, though caution is warranted in those with orthostatic hypotension. Testosterone deficiency, found in up to one-third of men with PD, may aggravate the issue but replacement therapy remains controversial.

Curiously, dopaminergic therapy can swing the pendulum too far—hypersexuality and compulsive behavior are recognized side effects of dopamine agonists. Managing sexual health in PD thus requires as much art as pharmacology, and above all, open conversation.

Thermoregulatory Dysfunction: The Forgotten Frontier

Sweating disturbances are among the most neglected symptoms of PD, yet they occur in 30–70% of patients. Both hyperhidrosis (excessive sweating) and hypohidrosis (reduced sweating) can appear, often asymmetrically.

The pathology is twofold: central involvement (Lewy body deposition in the hypothalamus) and peripheral autonomic neuropathy affecting sweat glands and vasomotor fibers. Patients may complain of cold, painful legs due to prolonged vasoconstriction, or of soaking sweats during “off” periods or dyskinesias.

Treatment is largely empirical: medication adjustment, temperature moderation, and, for localized sweating, botulinum toxin injections. The irony is not lost on clinicians—patients struggling with bradykinesia may simultaneously battle a thermostat gone rogue.

Why It Matters: Autonomic Dysfunction as a Prognostic Marker

Autonomic dysfunction is not merely a side effect of advanced PD; it is a core component of disease pathology. Early onset of autonomic symptoms correlates with faster cognitive decline, increased risk of falls, and reduced survival.

Moreover, autonomic symptoms often remain underreported. Patients may hesitate to mention them out of embarrassment or ignorance, and physicians may overlook them in favor of more visible motor issues. Routine screening with scales like SCOPA-AUT or Non-Motor Symptoms Questionnaire should therefore be part of every PD evaluation.

In the modern paradigm of personalized medicine, recognizing and treating autonomic dysfunction is not optional—it is integral to maintaining dignity, function, and independence in Parkinson’s patients.

Managing the Unmanageable: A Practical Synthesis

Treatment of autonomic dysfunction in PD is inherently multidisciplinary, blending neurology, cardiology, gastroenterology, and urology. The principles are universal:

- Identify reversible contributors—drugs, dehydration, comorbidities.

- Start with nonpharmacologic measures, reserving medication for persistent symptoms.

- Tailor therapy individually, recognizing that what elevates blood pressure may worsen urinary retention, and what dries saliva may precipitate constipation.

Above all, success depends on communication—between physician and patient, and among specialties. The goal is not perfection but balance: enough blood pressure to stand, enough motility to digest, enough dopamine to move, and enough humanity to live well.

Conclusion: Listening to the Quiet Systems

Parkinson’s disease is often described as a disorder of movement, but in truth, it is a disorder of integration—between mind and body, motor and autonomic, central and peripheral. The autonomic symptoms, though less conspicuous, are no less devastating.

From orthostatic hypotension to constipation, from urinary urgency to unpredictable sweating, each reflects the same underlying pathology: the silent unraveling of neural control. Yet each also offers an opportunity—for recognition, for treatment, and for restoring a measure of autonomy to those who are losing it.

In clinical practice, the most important lesson is simple: ask about the unseen. Because in Parkinson’s disease, the body whispers long before it shouts.

FAQ: Autonomic Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease

1. Can autonomic symptoms appear before motor signs in Parkinson’s disease?

Yes. Constipation, reduced smell, or orthostatic hypotension may precede tremor or rigidity by years, serving as potential early warning markers of neurodegeneration.

2. Is autonomic dysfunction treatable or reversible?

While the underlying neural damage is irreversible, many manifestations—such as orthostatic hypotension, constipation, and urinary urgency—are highly manageable with targeted therapy and lifestyle modification.

3. Why do some patients experience both low and high blood pressure?

Because of autonomic imbalance. Impaired baroreflexes lead to hypotension when upright and hypertension when supine. Managing this paradox requires careful timing of medication and positional strategies.