Introduction

Medicine often tries to separate the body from the mind, yet some disorders seem to defy that division. Erectile dysfunction (ED) and depression are two such conditions—each capable of amplifying the other in an almost perfect vicious cycle. The failure of one system, whether vascular or psychological, becomes the catalyst for dysfunction in the other.

Epidemiologic data illustrate the magnitude of this overlap. Roughly 52% of men aged 40–70 experience some degree of erectile dysfunction, from mild to complete impotence. Meanwhile, 16% of adults will face a major depressive episode in their lifetime, with another 10% experiencing minor depression. These are not rare comorbidities; they are overlapping epidemics.

Men with depression have nearly double the risk of developing ED compared to those without depression. Conversely, men suffering from ED frequently develop depressive symptoms, often driven by shame, diminished self-worth, and relationship strain. Yet in clinical practice, each condition is often treated in isolation—psychotherapy or antidepressants on one side, phosphodiesterase inhibitors on the other—leaving their shared biology insufficiently addressed.

Understanding this interdependence is not merely an academic exercise; it is essential for restoring both sexual and emotional health, which, as it turns out, are deeply inseparable.

The Bidirectional Relationship Between Depression and Erectile Dysfunction

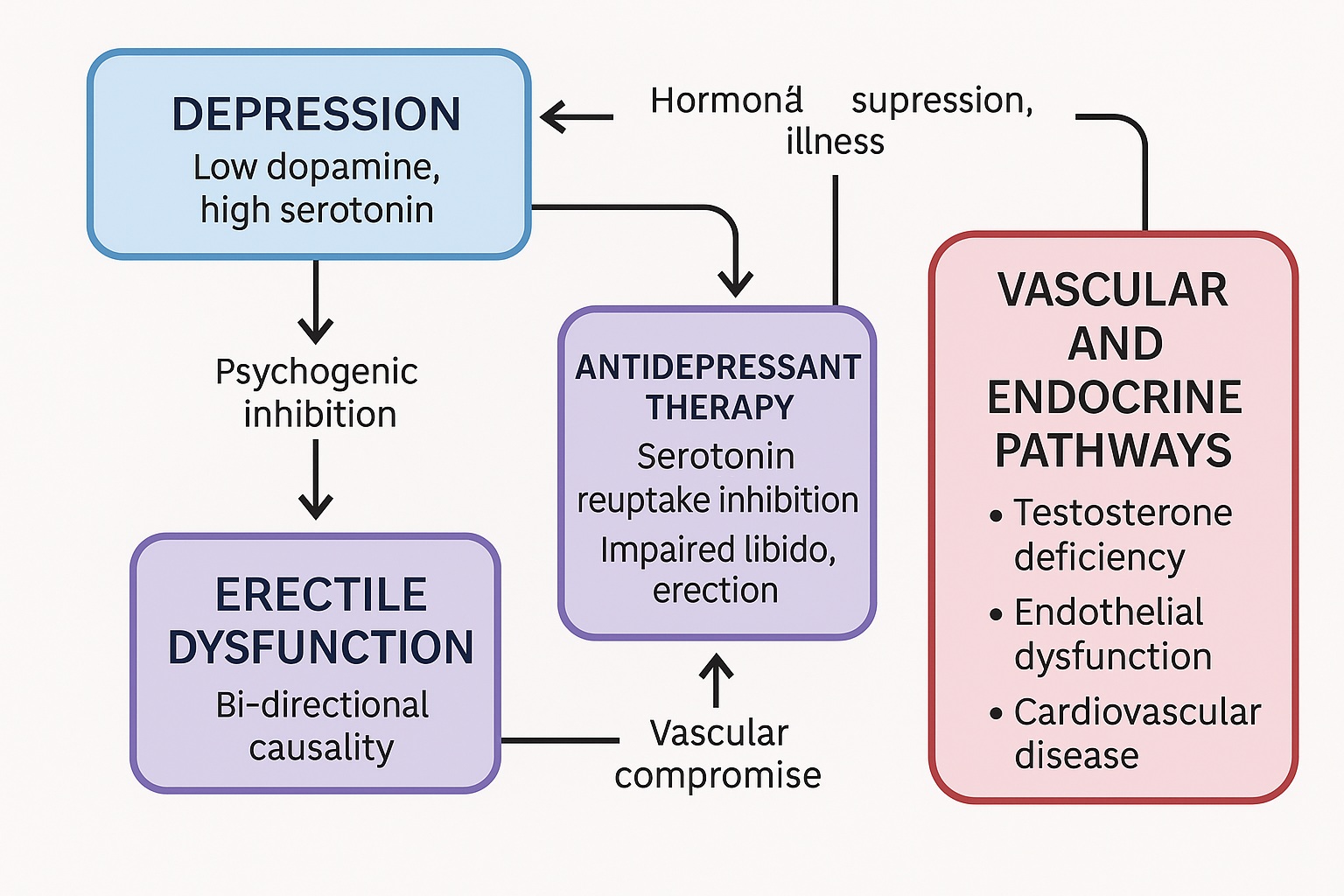

The relationship between depression and erectile dysfunction is biopsychosocial in the truest sense—anchored in neuroendocrine disruption, vascular compromise, and emotional distress.

From a biological standpoint, depression alters central dopaminergic and serotonergic signaling, both of which play pivotal roles in sexual desire and performance. Elevated serotonin levels, whether due to endogenous changes or pharmacologic manipulation, can suppress libido and delay orgasm. Simultaneously, diminished dopamine transmission reduces motivation and pleasure—the very psychological currency of sexual activity.

Psychologically, depression imposes a double burden: anxiety of failure and loss of desire. Men with depression often internalize sexual difficulty as evidence of inadequacy, compounding guilt and further blunting arousal. This cyclical interaction reinforces both disorders, making recovery more difficult unless treatment addresses both dimensions simultaneously.

On the vascular side, depression is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for endothelial dysfunction and ischemic heart disease, both of which share common inflammatory and metabolic pathways with ED. Thus, the penis may serve as an early barometer of cardiovascular health, and its dysfunction may signal systemic vascular compromise long before a heart attack or stroke occurs.

In short, ED is not only a symptom of psychological malaise—it is also a vascular and endocrine mirror reflecting deeper systemic illness.

Antidepressants: A Double-Edged Sword in the Treatment of Depression and Sexual Health

The irony of treating depression is that the very medications designed to restore mental health often erode sexual health. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), the mainstay of modern antidepressant therapy, are notorious for inducing sexual side effects—ranging from decreased libido to anorgasmia and erectile dysfunction.

The mechanisms are multifactorial. SSRIs elevate serotonin, which inhibits spinal reflexes and suppresses dopaminergic activity in reward pathways, effectively muting sexual motivation. Furthermore, they interfere with nitric oxide–mediated vasodilation, impairing erectile response. Clinically, up to 70% of patients report some degree of sexual dysfunction during SSRI therapy.

The consequences are not merely physical but behavioral. These side effects often lead to nonadherence or premature discontinuation of therapy—only about 30% of patients complete the recommended 6–9 months of antidepressant treatment after an acute episode. In a tragic feedback loop, sexual dysfunction undermines adherence, relapse follows, and both depression and sexual impairment return with greater ferocity.

Such patterns demand a strategic and empathetic approach to pharmacotherapy—one that acknowledges sexual function as central to well-being, not peripheral.

Clinical Strategies: Managing Antidepressant-Associated Sexual Dysfunction

Given the frequency and distress associated with antidepressant-induced ED, clinicians have developed several pragmatic strategies, though few have been rigorously validated in randomized trials.

Common approaches include:

- Preventive selection: choosing antidepressants with minimal sexual side effects, such as bupropion, mirtazapine, or vortioxetine.

- Switching agents: substituting the causative SSRI with a drug from a different pharmacologic class once depression stabilizes.

- Adjunctive therapy: adding a “sexual antidote,” such as a dopamine agonist, 5-HT antagonist, or non-serotonergic antidepressant.

- Drug holidays or dose reduction: cautiously attempted in selected cases but often impractical or risky for relapse.

While these strategies can be useful, most lack robust evidence, and their success is highly individualized. The inconsistency has led many clinicians to explore targeted pharmacologic antidotes—agents that directly reverse antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction without jeopardizing psychiatric stability.

Among these, one molecule stands out both in popularity and in mechanistic rationale: sildenafil citrate.

Sildenafil: From Erectile Aid to Antidepressant Antidote

Originally developed as a cardiovascular drug, sildenafil citrate (a selective phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor) serendipitously transformed the treatment of erectile dysfunction. By inhibiting the breakdown of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP), sildenafil amplifies nitric oxide signaling, facilitating smooth muscle relaxation and penile blood flow.

What makes sildenafil an ideal candidate for antidepressant-associated ED is its peripheral mechanism of action. Unlike central dopaminergic or serotonergic modulators, sildenafil does not interfere with mood regulation, making it a safe and noncompetitive adjunct to antidepressant therapy.

Clinical trials reviewed by Nurnberg and Hensley demonstrated sildenafil’s broad efficacy across etiologies of erectile dysfunction, including depression and antidepressant-induced cases. In double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, sildenafil improved erectile rigidity, penetration ability, and overall sexual satisfaction in men who had otherwise responded well to antidepressant therapy but developed sexual dysfunction as a side effect.

Its advantages extend beyond pharmacology: on-demand dosing, high tolerability, and rapid onset make sildenafil a practical antidote that restores not only physiological function but also patient confidence and adherence.

However, as with any potent vasodilator, physicians must consider contraindications—particularly cardiovascular disease and nitrate use—and evaluate whether the resumption of sexual activity itself poses undue risk.

The Hormonal and Cardiovascular Triad: Testosterone, Depression, and Erectile Function

The intersection of erectile dysfunction, depression, and cardiovascular disease forms a pathophysiologic triad that underscores the body’s integrative unity. Low testosterone, common with aging, mediates all three disorders to varying degrees.

Androgen decline contributes to fatigue, decreased libido, mood disturbances, and metabolic dysfunction—each of which predisposes to both depression and ED. Epidemiologic data indicate that age-related testosterone decreases parallel rising rates of both disorders, and that testosterone replacement therapy may partially alleviate symptoms in select patients.

However, the relationship is not purely hormonal. Depression itself may suppress hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function, while chronic illness and cardiovascular disease exacerbate endothelial and inflammatory damage. This overlap creates a synergistic pathology, where psychological stress, endocrine dysregulation, and vascular compromise coexist and reinforce one another.

The clinical message is clear: evaluating a man with erectile dysfunction should include not only psychiatric assessment but also hormonal and cardiovascular screening. To treat one in isolation is to risk failure in all.

Depression, Heart Disease, and the Shared Vascular Pathway

Modern research increasingly views depression as a vascular disorder—one that alters endothelial function, platelet activity, and inflammatory signaling. These same pathways contribute to ischemic heart disease (IHD) and erectile dysfunction.

Studies have confirmed associations between depression and IHD, IHD and ED, and ED and depression—forming a triad of interlinked morbidity. In practical terms, a middle-aged man presenting with both depressive symptoms and ED may, in fact, be exhibiting the earliest signs of systemic vascular disease.

This understanding shifts the clinical lens: managing ED and depression becomes not only a matter of sexual and emotional health but also of cardiovascular prevention. Lifestyle modification, exercise, and vascular-protective pharmacotherapies (such as statins or ACE inhibitors) can, therefore, complement both psychiatric and sexual rehabilitation.

Thus, the penis, once dismissed as a mere symbol of virility, may serve as a sentinel organ for systemic well-being.

Integrating Care: The Future of Psychosexual Medicine

As evidence accumulates, it becomes increasingly untenable to treat ED or depression as isolated entities. Both require an integrated, multidisciplinary approach combining psychiatry, endocrinology, and urology.

An optimal management framework includes:

- Early recognition and open communication about sexual side effects of antidepressants.

- Regular screening for depression in men presenting with ED, especially in those with chronic illness.

- Concurrent management of vascular and metabolic comorbidities.

- Personalized pharmacotherapy, possibly combining antidepressants with PDE5 inhibitors or hormonal modulators.

Emerging research suggests that treating erectile dysfunction can improve mood independently of antidepressant therapy—likely through restoration of self-esteem and relational intimacy. Likewise, effectively managing depression can normalize sexual function by reducing psychogenic inhibition.

In other words, recovery in one domain often catalyzes recovery in the other, underscoring the need for holistic treatment pathways that view sexuality and emotional health as mutually sustaining aspects of human function.

Conclusion

The coexistence of erectile dysfunction and depression represents more than a statistical coincidence—it is a physiological and psychological continuum. Each can trigger, sustain, or exacerbate the other, and both share deep commonalities in neurochemistry, endocrinology, and vascular biology.

Modern management must therefore transcend the boundaries between psychiatry and urology, adopting a systems-based perspective. Whether through hormonal optimization, antidepressant adjustment, or adjunctive use of sildenafil, success depends on recognizing the interdependence of mood and erection—a relationship that is at once biological and profoundly human.

Ultimately, the goal is not merely to restore potency or relieve sadness but to reintegrate the patient’s sense of vitality and identity. In doing so, medicine fulfills its oldest promise: the healing of the whole person.

FAQ: Depression and Erectile Dysfunction

1. Why do antidepressants cause erectile dysfunction?

Most antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, increase serotonin activity, which suppresses dopamine and nitric oxide pathways vital for sexual arousal and erection. This neurochemical imbalance diminishes libido and impairs erectile function.

2. Can sildenafil safely be used with antidepressants?

Yes, in most cases. Sildenafil works peripherally through the nitric oxide–cGMP pathway and does not interfere with central neurotransmission. It can safely restore erectile function in men whose depression is well-controlled, provided cardiovascular contraindications are absent.

3. Is low testosterone responsible for both depression and ED?

Partially. Testosterone deficiency contributes to both mood decline and sexual dysfunction, especially in aging men. However, not all cases of depression or ED are hormone-driven—vascular, psychological, and medication-related factors also play significant roles.