Introduction: When Biology Defies Expectation

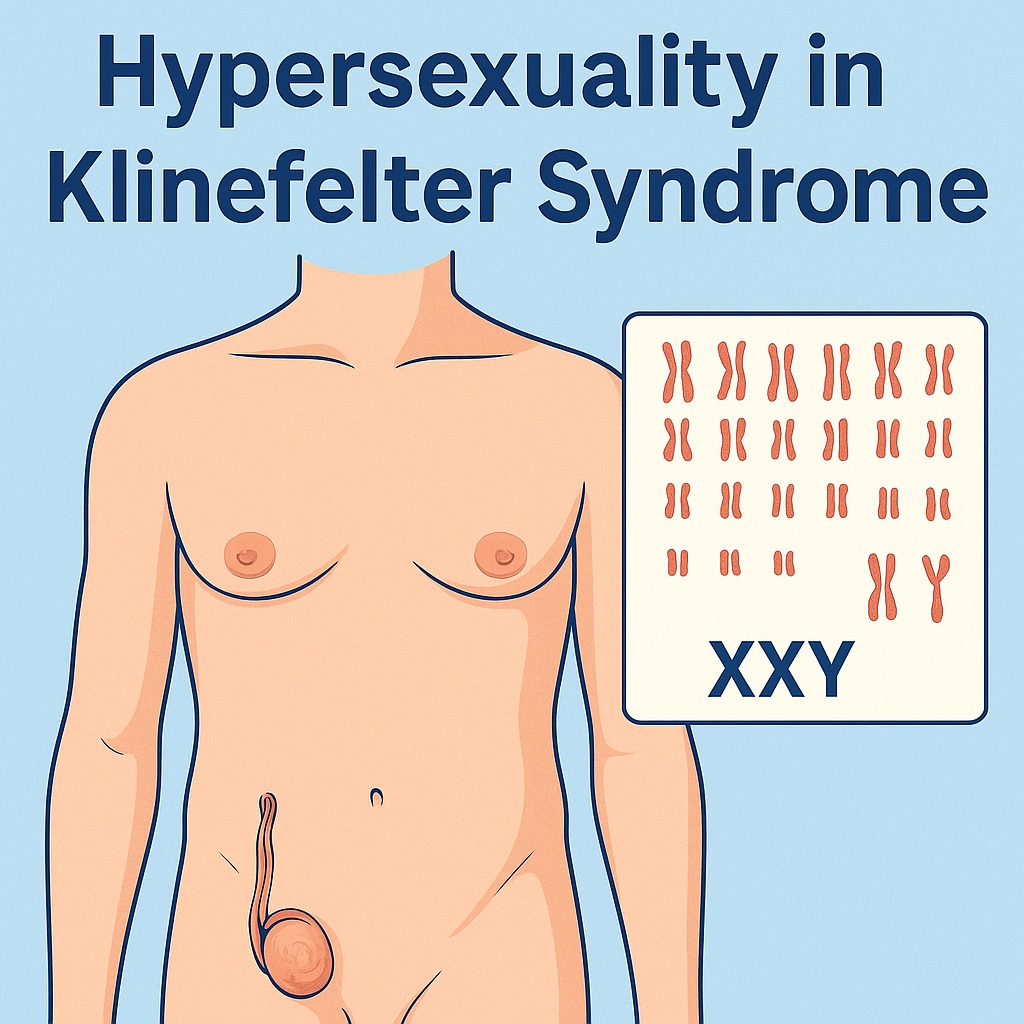

Klinefelter syndrome (KS) is a genetic enigma that quietly challenges our assumptions about masculinity, hormones, and human behavior. Traditionally defined by the karyotype 47,XXY, KS is the most common sex chromosomal abnormality in males, affecting approximately one in 600 men. It is classically associated with testicular failure, androgen deficiency, infertility, and reduced libido. Yet, as medicine often reminds us, there are exceptions that defy the rule.

In recent years, case studies have revealed a handful of men with KS who, despite having low testosterone levels and erectile dysfunction, experience hypersexuality — a heightened, sometimes compulsive sexual drive. These rare presentations have forced clinicians to reconsider the simplistic notion that libido is solely dependent on testosterone.

The following discussion explores this paradox — how a man with Klinefelter syndrome, a condition defined by hypogonadism, could present with overwhelming sexual desire. The case underscores the interplay between neuroendocrine, psychological, and behavioral factors in sexual function and examines the ethical and clinical challenges of managing such a patient, particularly when there is a history of sexual offending.

Understanding Klinefelter Syndrome: The Silent Male Hypogonadism

Klinefelter syndrome results from nondisjunction of the X chromosome, leading to an extra X (most commonly 47,XXY). Variants include mosaics (46,XY/47,XXY) and higher-order aneuploidies such as 48,XXXY or 49,XXXXY. The phenotype varies widely depending on the degree of mosaicism and the timing of chromosomal nondisjunction.

Boys with KS typically enter puberty at the expected age and initially experience normal increases in testosterone. However, by mid-puberty, testosterone levels decline and gonadotropins rise, producing the classic picture of hypergonadotropic hypogonadism. The result is testicular atrophy, reduced facial and body hair, gynecomastia, and infertility.

Despite its frequency, up to 75% of adult cases remain undiagnosed. Many individuals never receive the diagnosis until adulthood, often during infertility evaluations or investigations for hypogonadism. Early recognition remains poor partly because of the heterogeneous presentation, which may include cognitive, behavioral, or psychiatric features rather than overt endocrine symptoms. Boys may be referred for learning difficulties, especially delayed verbal development and poor social integration, long before anyone suspects an underlying chromosomal disorder.

Clinically, the picture is that of a tall, somewhat effeminate man with small testes, sparse body hair, and features of low androgenization. Less visible, but equally important, are the psychosocial and cognitive difficulties that accompany KS — elements that can shape personality, interpersonal relationships, and sexual behavior.

The Case That Rewrote Expectations

The patient at the heart of this discussion was a 44-year-old man diagnosed with mosaic Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY/48,XXXY/46,XY). His presentation, however, was anything but typical. Despite having erectile dysfunction and biochemical hypogonadism, he reported intense and uncontrollable sexual urges, leading to frequent masturbation and thousands of sexual encounters, most with commercial sex workers.

By his own account, he had over 1,800 sexual partners, engaged in compulsive sexual activity, and described his condition as “sexual addiction.” His hypersexual behavior had led to legal consequences — a sexual offence conviction at age 17. Though he denied attraction to minors, the early incident underscored the potential for impulsive, socially destructive behavior when sexual drive exceeds self-control.

The paradox was striking: a man with objectively low testosterone and erectile difficulties driven by hypersexual desire. This juxtaposition — diminished physical capacity but heightened mental and emotional sexual preoccupation — challenges the traditional endocrine model of libido.

His medical history revealed additional complexities: obesity, obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, and gout. Psychologically, he had learning difficulties, features of autism spectrum disorder, and social challenges that had persisted since childhood. He lived alone, had no long-term relationships, and sought satisfaction through transient encounters.

In short, he was a man caught between biology and behavior, physiology and compulsion — a case that demands both empathy and scientific curiosity.

Diagnosis and the Mosaic Puzzle

Laboratory investigations confirmed hypergonadotropic hypogonadism, with low testosterone (≈6.5 nmol/L) and elevated LH and FSH. MRI of the pituitary was normal, ruling out secondary causes. Cytogenetic analysis demonstrated a mosaic karyotype with 47,XXY as the predominant cell line, accompanied by a small fraction of 48,XXXY and 46,XY cells. This pattern suggests a degree of phenotypic variation — perhaps explaining why his androgen deficiency was mild compared to classical KS.

He also exhibited osteopenia, borderline impaired glucose tolerance, and mild thyroid hormone variations — all common in KS due to the interplay between hypogonadism, metabolic dysfunction, and altered energy regulation.

Psychologically, the patient described lifelong social isolation and language difficulties, consistent with known neurocognitive features of KS. These findings highlight that Klinefelter syndrome is as much a neurodevelopmental condition as an endocrine one. The presence of learning difficulties, autism traits, and behavioral rigidity likely influenced his approach to relationships and sexuality.

Hypersexuality: When Desire Escapes Hormonal Control

Hypersexuality in a hypogonadal male appears paradoxical, but it is not without precedent. In rare instances, libido can become disconnected from androgen levels, driven instead by central nervous system mechanisms involving dopamine and acetylcholine.

Neurobiologically, libido arises from a complex network integrating hormonal, limbic, and cortical inputs. While testosterone enhances sexual motivation through activation of hypothalamic centers, dopamine within the mesolimbic system — the brain’s reward pathway — plays an equally critical role. In certain individuals, dopaminergic hyperactivity can override hormonal suppression, resulting in excessive sexual desire even in the absence of normal androgen levels.

Indeed, hypersexuality has been observed as an adverse effect of dopamine agonists in patients with Parkinson’s disease and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in those with dementia. These cases suggest that neurotransmitter dysregulation, not hormones alone, can generate sexual compulsion.

In this patient, features of autism spectrum disorder and impulsivity may have compounded this dysregulation. His obsessive sexual behavior resembles the repetitive, fixated patterns common in neurodevelopmental disorders. Furthermore, early-life social isolation and low emotional literacy may have conditioned him to equate sexual activity with social connection, fueling the compulsive cycle.

This framework invites an important reconsideration: libido is not simply an endocrine function — it is a biopsychosocial phenomenon. And in KS, where brain structure and function are subtly altered, that balance can tip in unexpected directions.

Ethical and Clinical Dilemmas in Treatment

Treating hypogonadism in a man with hypersexuality and a prior sexual offence presents a delicate ethical challenge. Testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) is the cornerstone of KS management, improving mood, muscle mass, bone density, and overall vitality. However, it also carries the risk of exacerbating sexual drive and potentially increasing behavioral risk in vulnerable individuals.

In this case, a multidisciplinary team was convened — including an endocrinologist, forensic psychiatrist, psychologist, and general practitioner. The team faced a fundamental tension: addressing the legitimate medical need for testosterone versus minimizing the potential for socially harmful behavior.

After careful deliberation, low-dose, short-acting testosterone was initiated (topical 2% Axiron, 30 mg daily). This approach allowed for gradual titration and rapid withdrawal if side effects occurred. Over several weeks, the patient experienced improved mood and energy, but continued to report mood swings. He was switched to a low-dose transdermal patch (Androderm 2.5 mg/day), with stabilization and modest improvement in well-being.

Interestingly, his libido did not increase further on therapy — an encouraging outcome suggesting that his hypersexual drive was not testosterone-dependent. The addition of an SSRI (fluoxetine) was recommended to dampen excessive sexual preoccupation while improving mood. Although he declined pharmacotherapy, he agreed to ongoing psychotherapy.

Such careful balancing acts are not uncommon in endocrinology, but in this case, the stakes were unusually high. Managing hormones means managing human behavior — and that requires both compassion and caution.

Neurocognitive and Psychiatric Dimensions of Klinefelter Syndrome

The case underscores the neuropsychiatric complexity of KS. Beyond endocrine symptoms, many affected individuals exhibit mild to moderate impairments in language, social cognition, and executive function. Studies consistently show poorer performance in verbal IQ compared to performance IQ, along with increased rates of autism spectrum traits, ADHD, and mood disorders.

These cognitive vulnerabilities often shape behavior more profoundly than the hormonal deficiency itself. Social awkwardness, emotional immaturity, and reduced empathy can contribute to interpersonal misunderstandings or maladaptive coping mechanisms, including compulsive or risky sexual behavior.

It is also worth noting that not all behavioral differences in KS are pathological. Some men demonstrate extraordinary sensitivity, creativity, or verbal eloquence — a reminder that neurodiversity in KS spans a wide range. Nonetheless, when psychiatric features overlap with endocrine dysfunction, the clinical picture becomes multifaceted and requires integrated, rather than siloed, care.

Early diagnosis and psychosocial support can mitigate these challenges. Awareness among pediatricians, educators, and mental health professionals remains essential to prevent decades of undiagnosed suffering — as was the case here, where the diagnosis came only in midlife.

The Testosterone–Crime Connection: Myth or Mechanism?

One of the more controversial aspects of the case involves the association between testosterone levels and sexual offending. Some studies have suggested that higher testosterone correlates with increased aggression and sexual reoffending. In a cohort of over 500 male sex offenders, elevated testosterone was linked to more invasive offenses and higher recidivism rates.

However, causality is far from established. Testosterone may amplify underlying impulsivity or reward-seeking behavior but is not a direct driver of criminality. In fact, most men with normal or high testosterone levels exhibit socially appropriate sexual behavior.

What matters most is context and control. In hypogonadal men, restoring physiological testosterone levels typically enhances mood and cognitive stability — not aggression. The risk emerges only when high doses are administered or when psychiatric vulnerabilities go unaddressed.

Hence, the ethical imperative: to treat biological deficiency responsibly, with vigilant monitoring and multidisciplinary oversight. In this case, short-acting preparations were wisely chosen, ensuring safety and reversibility.

Lessons for Clinical Practice

This unusual case yields several key lessons for clinicians:

- Always think of Klinefelter syndrome in men with unexplained hypogonadism, infertility, or learning difficulties.

- Libido is not exclusively hormonal — central neurotransmitter pathways and psychological factors can independently modulate sexual drive.

- Testosterone therapy in hypersexual patients should be introduced cautiously, ideally under joint supervision by endocrinology and psychiatry.

- Early diagnosis and cognitive support in childhood can prevent later psychosocial complications.

- And perhaps most importantly, patients with KS deserve empathy, not stigma — their challenges are often as emotional and social as they are physical.

This case also reminds us that medicine’s neat categories — hypogonadism equals low libido, testosterone equals virility — are sometimes undone by human complexity. The intersection of genetics, neurology, and psychology does not always obey linear logic.

The Broader Implications: Rethinking Libido and Masculinity

The paradox of hypersexuality in KS invites broader reflection on how we define masculinity and sexual normalcy. For decades, testosterone has been treated as the essence of male sexual function — the biochemical embodiment of desire. Yet, as this case illustrates, desire can persist, even flourish, outside hormonal boundaries.

This decoupling of libido from androgen levels highlights the brain’s autonomy in sexual motivation. Neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin, early conditioning, and personality structure all shape libido as much as endocrine function does.

From a sociocultural perspective, KS challenges stereotypes: the “less masculine” man with small testes and sparse hair who nevertheless experiences overwhelming sexual drive. Such contradictions reveal how biological diversity defies simplistic gender constructs.

In a sense, this case is not about pathology alone — it is about human variability, how genes and hormones intersect with psyche and society to produce the full spectrum of male experience.

Conclusion: When Medicine Meets Paradox

Klinefelter syndrome has long been viewed as a quiet, underdiagnosed cause of male infertility and hypogonadism. Yet cases like this one remind us that medicine is full of paradoxes. A man with low testosterone but uncontrollable desire forces us to expand our understanding of sexual physiology and human behavior.

This patient’s story illustrates three intertwined truths:

- KS is more than an endocrine disorder — it is a neurodevelopmental condition with psychological and behavioral dimensions.

- Libido cannot be reduced to testosterone alone — the brain’s reward circuitry often plays the dominant role.

- Ethical, multidisciplinary management is essential when treating hormone deficiency in individuals with behavioral risk factors.

Ultimately, medicine’s task is not to fit every patient into a predictable model but to recognize and responsibly navigate exceptions. The real art of endocrinology lies in balancing hormones and humanity — one patient, and one paradox, at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. Can a man with low testosterone have high sexual desire?

Yes. While testosterone contributes to libido, it is not the sole determinant. Dopamine and other neurotransmitters in the brain’s reward system can independently drive sexual motivation, sometimes resulting in hypersexuality despite hypogonadism.

2. Is testosterone therapy safe in men with a history of hypersexual or criminal behavior?

It can be, but requires caution. Therapy should begin at low doses with short-acting formulations and close psychiatric monitoring. The goal is to restore physiological levels, not to enhance libido.

3. What is the key to managing Klinefelter syndrome effectively?

Early diagnosis and holistic care. Beyond hormone replacement, attention must be given to learning difficulties, emotional health, and social integration. A multidisciplinary approach combining endocrinology, psychology, and education provides the best long-term outcomes.