Introduction

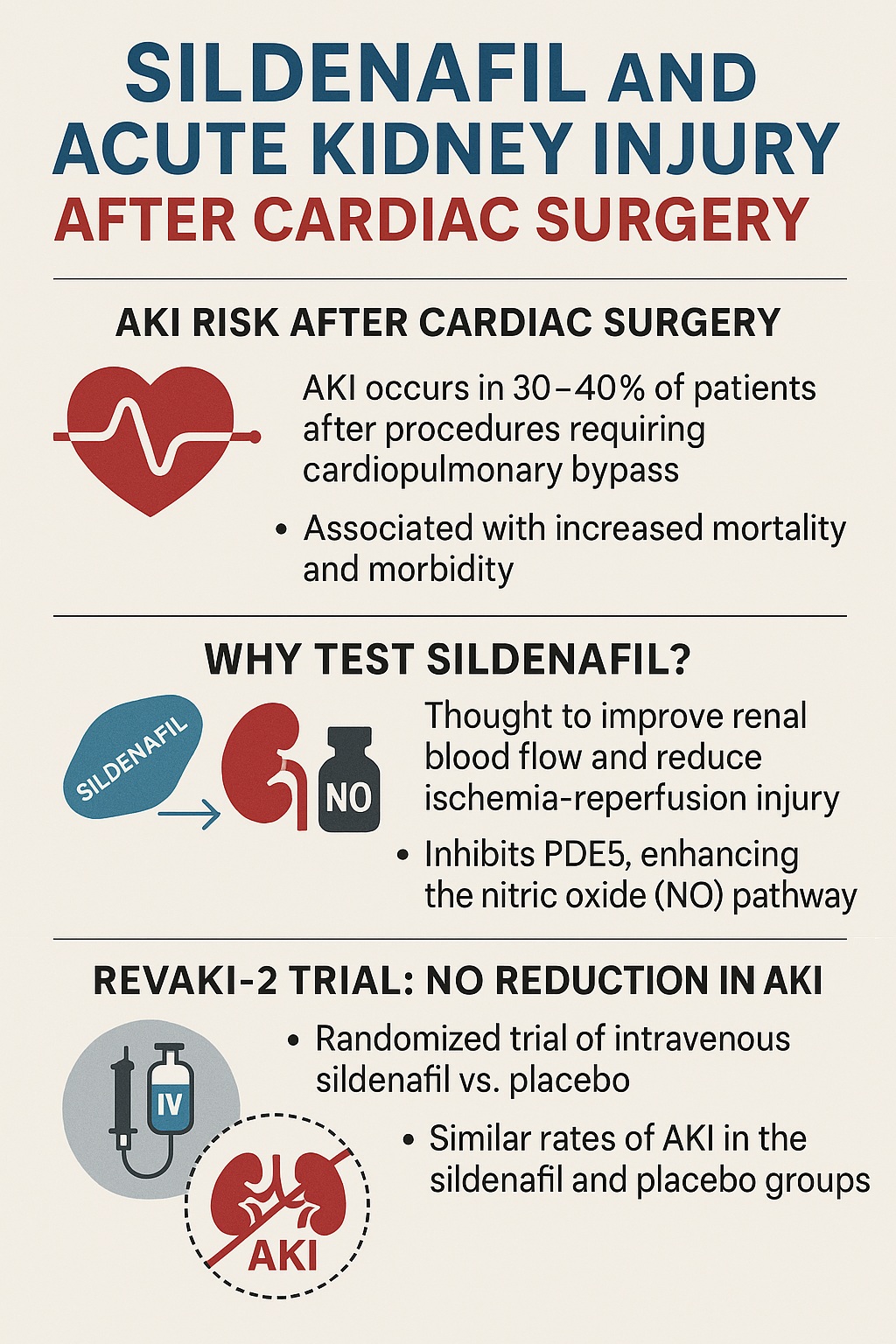

Cardiac surgery has become safer, faster, and more predictable over the past half century, but its complications remain sobering. Among them, acute kidney injury (AKI) stands out as both common and deadly. Depending on the definition used, AKI occurs in 30–40% of patients after procedures requiring cardiopulmonary bypass, and in severe cases may lead to dialysis dependence, prolonged hospitalization, or death. The modern cardiac surgeon, therefore, wages two parallel battles: repairing the failing heart while protecting the vulnerable kidneys.

Pharmacologic prevention of AKI has long been a tantalizing prospect. Agents ranging from diuretics to antioxidants have been tested with limited success. Recently, attention turned to sildenafil citrate, better known as a treatment for erectile dysfunction and pulmonary arterial hypertension. By inhibiting phosphodiesterase type 5 (PDE5), sildenafil enhances nitric oxide–mediated cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling, leading to vasodilation, improved microvascular flow, and reduced ischemia–reperfusion injury. Preclinical models suggested renoprotective effects, igniting hopes that sildenafil might protect kidneys exposed to the inflammatory storm of cardiac surgery.

The REVAKI-2 trial, published in 2020, put this hypothesis to the test in a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Its findings were sobering: intravenous sildenafil did not reduce the incidence of AKI following cardiac surgery. Yet, as with all negative trials, its value lies not in disappointment but in clarification. By examining what worked, what did not, and why expectations diverged from reality, we learn how to refine both science and practice.

Why Focus on Acute Kidney Injury in Cardiac Surgery?

The kidney, though often overlooked compared to the heart and brain, is exquisitely sensitive to ischemia, inflammation, and hemodynamic instability. Cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB)—a marvel of modern medicine—unintentionally creates the perfect storm for renal injury. Blood is shunted through artificial circuits, triggering complement activation and systemic inflammation. Non-pulsatile flow reduces renal perfusion. Hemodilution lowers oxygen delivery, while reperfusion after ischemic intervals generates oxidative stress.

AKI after cardiac surgery is not a trivial complication. Even mild elevations in serum creatinine double mortality risk, while severe AKI requiring dialysis carries mortality rates exceeding 50%. Long-term outcomes are also dire: survivors often progress to chronic kidney disease, amplifying cardiovascular morbidity in a vicious cycle. Economically, AKI adds days or weeks to hospitalization and drives intensive care utilization.

Given these stakes, the pursuit of a renoprotective pharmacologic intervention is not academic curiosity but urgent necessity. If sildenafil—or any agent—could reduce AKI incidence by even a modest margin, the population-level benefit would be enormous. The REVAKI-2 trial thus aimed to answer not only a scientific question but a pressing clinical one.

Biological Rationale for Sildenafil in AKI

Why sildenafil? The rationale derives from its effects on vascular tone, endothelial health, and ischemia–reperfusion injury. By blocking PDE5, sildenafil sustains intracellular cGMP levels, augmenting nitric oxide signaling. The result is smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilation, particularly within the pulmonary and systemic vasculature. In the kidney, enhanced perfusion at the microvascular level could theoretically prevent ischemic injury to the vulnerable renal medulla.

Animal models of renal ischemia–reperfusion injury consistently demonstrated protective effects of sildenafil. Rodents pretreated with sildenafil showed reduced tubular necrosis, preserved glomerular filtration, and attenuated inflammatory cytokine release. In large-animal models, sildenafil improved renal oxygenation and reduced apoptotic signaling. Translational enthusiasm grew when small pilot human studies hinted at improved renal biomarkers after sildenafil exposure.

Furthermore, sildenafil’s track record in pulmonary hypertension reassured clinicians of its safety profile, even in critically ill patients. If a drug already in widespread use could be repurposed to prevent AKI, the impact would be profound. REVAKI-2 was thus designed not as an exploratory curiosity but as a definitive test of an attractive hypothesis.

Design of the REVAKI-2 Trial

The REVAKI-2 trial was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in patients undergoing elective or urgent cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. Participants were randomized to receive either intravenous sildenafil or placebo before and during surgery. The dosing regimen was carefully calibrated to achieve plasma concentrations thought to be renoprotective without inducing systemic hypotension.

The primary endpoint was incidence of AKI within the first seven days postoperatively, defined using the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria. Secondary endpoints included severity of AKI, need for renal replacement therapy, hospital length of stay, and all-cause mortality. Biomarker analysis of renal injury (including NGAL and KIM-1) was also performed to provide mechanistic insights.

This design reflected the highest standards of contemporary clinical trials: rigorous randomization, double-blinding, and clinically meaningful outcomes. It was not a pilot but a definitive test of sildenafil’s renoprotective potential in real-world surgical patients.

The Results: A Sobering Reality

The trial’s findings were unequivocal. Intravenous sildenafil did not reduce the incidence of AKI compared to placebo. Approximately 47% of patients in the sildenafil arm developed AKI, versus 49% in the placebo arm—a difference that was neither statistically nor clinically significant. The severity of AKI, rates of renal replacement therapy, and hospital length of stay were also indistinguishable between groups.

Biomarker analysis mirrored these clinical outcomes. Levels of NGAL and KIM-1, sensitive indicators of tubular injury, were not improved with sildenafil administration. Hemodynamic monitoring revealed no major adverse effects—blood pressure remained stable, and there were no excess cardiac arrhythmias or unexpected toxicities. Thus, the trial was not negative because of harm but because of lack of efficacy.

For those who hoped sildenafil might be the long-sought pharmacologic shield against AKI, the results were disappointing. But in the broader arc of science, negative results are clarifying. The trial demonstrated with high certainty that sildenafil, at clinically tolerable doses, does not meaningfully prevent AKI in the context of cardiac surgery.

Why Did Sildenafil Fail?

The divergence between preclinical promise and clinical futility is not unusual in translational medicine. Several factors may explain why sildenafil failed to deliver in the REVAKI-2 trial.

First, complexity of human AKI dwarfs animal models. In rodents, ischemia–reperfusion injury is often the dominant insult. In cardiac surgery, however, renal injury arises from a chaotic interplay of hemodynamics, inflammation, oxidative stress, embolic phenomena, and comorbidities such as diabetes or hypertension. A drug targeting a single pathway may be overwhelmed by this multifactorial assault.

Second, timing and dosing may have been suboptimal. In animal models, sildenafil is often administered before ischemia in controlled conditions. In humans, variability in surgical duration, perfusion pressures, and individual pharmacokinetics may blunt its protective effect. Doses high enough to replicate experimental efficacy could induce hypotension—catastrophic in the perioperative setting. The trial thus walked a tightrope between theoretical efficacy and clinical safety.

Third, patient heterogeneity is unavoidable. Unlike homogeneous lab animals, cardiac surgery patients vary in age, comorbidities, baseline renal function, and vascular health. These variables dilute effect sizes, especially when the intervention itself is modest. Subgroup analyses in REVAKI-2 did not reveal hidden benefits in particular populations, but the possibility of differential responses cannot be excluded entirely.

Ultimately, the trial’s negative outcome underscores a sobering truth: preclinical enthusiasm rarely survives the crucible of human complexity.

Clinical Implications

For clinicians, the message is clear: sildenafil should not be used to prevent AKI after cardiac surgery. Its administration neither improves renal outcomes nor alters secondary measures of morbidity or mortality. The drug’s role remains confined to established indications such as erectile dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension.

This conclusion is not merely academic but practical. Many patients and families, aware of sildenafil’s popularity, may inquire about its off-label use in surgical settings. Armed with the REVAKI-2 data, clinicians can confidently explain that rigorous trials have shown no benefit. The allure of repurposing familiar drugs must be tempered by evidence, not anecdote.

Yet, the trial also offers reassurance. Sildenafil did not cause harm, even in critically ill surgical patients. For those already taking the drug for other indications, continuation during the perioperative period appears safe. Thus, while sildenafil is not protective, it is not dangerous in this context—a nuance worth communicating to patients.

Broader Lessons From REVAKI-2

The trial illustrates several broader lessons about translational medicine. First, it highlights the limitations of animal models. Rodents provide mechanistic clarity but rarely replicate the chaotic complexity of human disease. Drugs that protect rat kidneys in sterile laboratory ischemia may falter when confronted with the inflammatory storm of human surgery.

Second, it reminds us of the importance of negative trials. In a field littered with small, optimistic pilot studies, definitive negative data are invaluable. They prevent wasted resources, protect patients from ineffective interventions, and redirect attention to more promising avenues. In this sense, REVAKI-2 is not a failure but a public service.

Third, the trial emphasizes that multifactorial problems demand multifactorial solutions. AKI after cardiac surgery does not yield to a single pharmacologic agent. Instead, prevention likely requires bundles of interventions: meticulous perfusion management, avoidance of nephrotoxins, optimization of hemodynamics, and perhaps novel agents targeting multiple pathways simultaneously. Sildenafil, unfortunately, is not part of this bundle.

Future Directions in AKI Prevention

If sildenafil has failed, what next? The quest to prevent AKI after cardiac surgery continues, guided by several promising avenues.

One approach is the development of biomarker-guided risk stratification. By identifying patients at highest risk preoperatively, interventions can be targeted more effectively. Novel biomarkers such as TIMP-2 and IGFBP7 may allow earlier detection of renal stress, enabling preemptive protective strategies.

Pharmacologic research is also diversifying. Agents targeting mitochondrial protection, complement inhibition, and anti-inflammatory pathways are under investigation. Unlike sildenafil, these drugs aim to blunt the systemic storm rather than simply improve perfusion.

Finally, non-pharmacologic strategies remain central. Enhanced recovery protocols, individualized perfusion strategies, and careful fluid management may ultimately prove more effective than any pill or infusion. The future of AKI prevention is likely to be pragmatic, integrative, and multimodal, rather than hinging on a single agent.

Conclusion

The REVAKI-2 trial sought to answer a pressing question: can sildenafil, a familiar and well-tolerated drug, prevent AKI after cardiac surgery? The answer, delivered with clarity, is no. Despite a compelling biological rationale and encouraging preclinical data, sildenafil failed to reduce AKI incidence, severity, or downstream outcomes.

For clinicians, the lesson is restraint. Evidence must guide practice, and in this case, evidence dictates against sildenafil’s use as a renoprotective agent. For researchers, the trial underscores the need to rethink strategies for AKI prevention, embracing the complexity of human disease rather than seeking single-molecule solutions.

Negative though it may seem, REVAKI-2 enriches our understanding. It narrows the field, clarifies priorities, and protects patients from false hope. In the relentless pursuit of safer cardiac surgery, knowing what does not work is just as important as knowing what does.

FAQ

1. Does sildenafil protect the kidneys after cardiac surgery?

No. The REVAKI-2 trial showed that intravenous sildenafil did not reduce the incidence or severity of AKI following cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass.

2. Is it safe to continue sildenafil in patients already taking it for pulmonary hypertension or erectile dysfunction during surgery?

Yes. The trial found no evidence of harm from perioperative sildenafil use. While it does not prevent AKI, it does not increase risk either.

3. What strategies are currently effective in preventing AKI after cardiac surgery?

Prevention is best achieved through multimodal care: careful management of perfusion pressures, avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs, early risk stratification, and optimized fluid balance. No single pharmacologic agent, including sildenafil, has proven effective.