Introduction

Testosterone therapy has experienced a renaissance in recent decades. Once confined to men with well-documented hypogonadism, its prescription has broadened dramatically. Today, men well under the threshold of deficiency are often treated, sometimes without even a confirmatory hormone measurement. The promises of renewed vitality, improved muscle strength, and restored libido are seductive. Yet, lurking behind this pharmacological fountain of youth is a question as old as medicine itself: at what cost?

The clinical community has grown increasingly uneasy with the cardiovascular consequences of testosterone replacement. While advertisements present it as a straightforward ticket to rejuvenation, scientific data paint a far more complicated picture. Recent studies, including robust cohort analyses, point to an association between testosterone prescriptions and an increased incidence of non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI). The stakes are high. Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and the introduction of additional, preventable risks into an already burdened system cannot be ignored.

This article explores in depth the evidence linking testosterone therapy to myocardial infarction, the nuances of risk stratification across age and cardiac history, the biological plausibility underlying these findings, and the practical implications for clinicians and patients alike. We aim to move past the polarized rhetoric surrounding testosterone and instead evaluate where enthusiasm ends and caution must begin.

Testosterone Therapy in Context

To understand the present dilemma, one must first appreciate the historical and clinical evolution of testosterone therapy. Initially, the hormone was reserved for men with classical hypogonadism—conditions such as pituitary insufficiency or testicular failure. The therapeutic aim was narrow: to restore physiologic hormone levels in men suffering from overt endocrine dysfunction. However, the 21st century has seen a cultural and clinical shift. Testosterone is now framed as a lifestyle enhancer rather than a corrective agent. Prescription rates have soared in younger men and even in those without baseline testing, underscoring the blurred boundaries between therapeutic necessity and consumer-driven demand.

The indications for testosterone are now far more expansive, often justified by nonspecific symptoms: fatigue, low mood, or decreased sexual desire. While these may indeed reflect hypogonadism in some cases, they may equally signal stress, depression, or normal aging. The pharmaceutical industry’s role in shaping perception should not be underestimated. Advertising campaigns emphasize vigor and masculinity, equating testosterone with a return to youthful virility. This messaging has led many men to seek therapy without appreciating the potential consequences.

Within this broader clinical context, the cardiovascular risks assume new gravity. When testosterone was used sparingly, adverse events might have been considered acceptable trade-offs in truly deficient patients. Today, however, the sheer scale of prescriptions means that even a modest increase in myocardial infarction risk translates into a substantial population burden. The issue is no longer academic—it is a public health concern demanding urgent clarity.

The Evidence of Risk

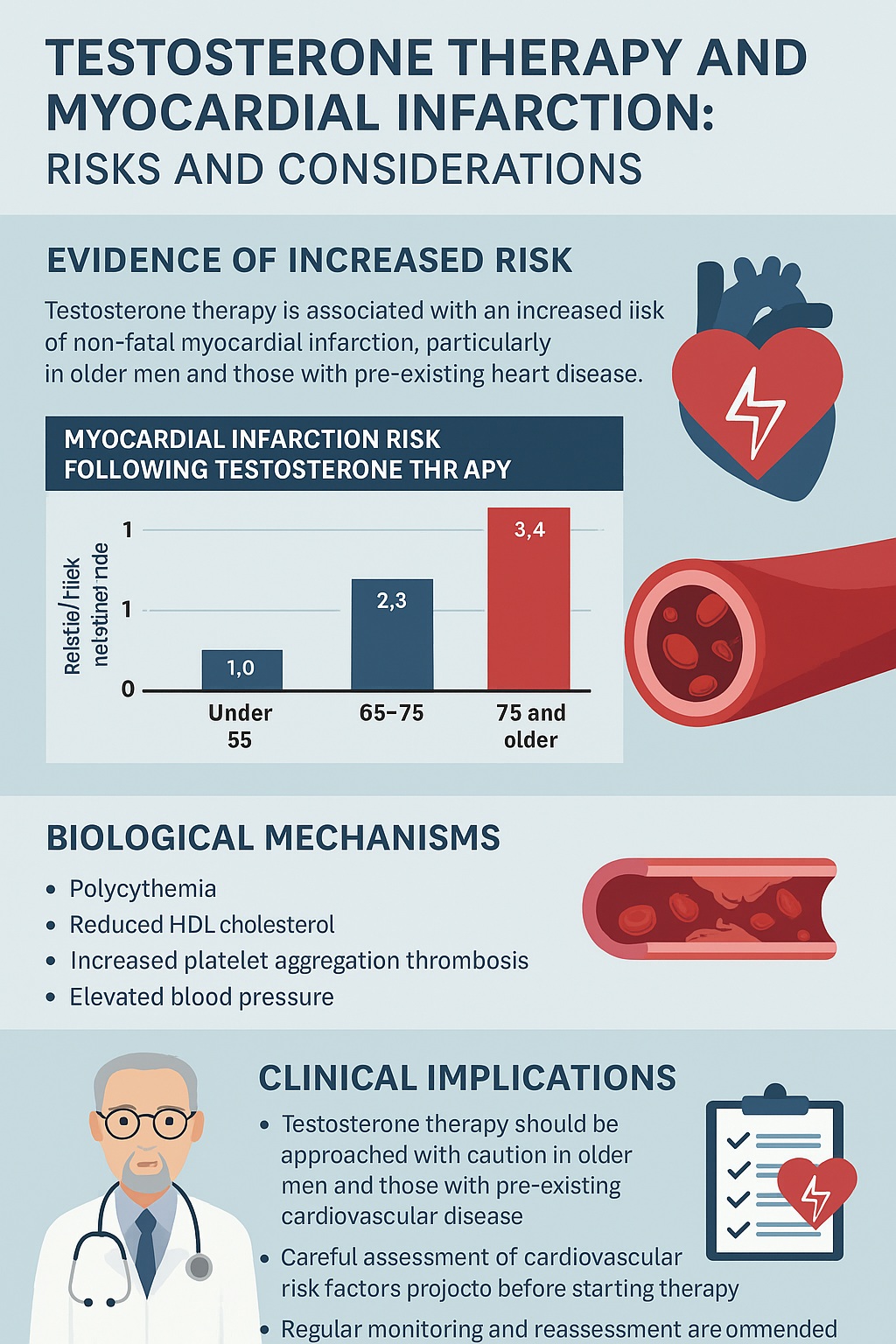

The strongest evidence linking testosterone therapy to cardiovascular events comes from large-scale observational studies and meta-analyses. The study at the center of this discussion evaluated over 55,000 men who received testosterone prescriptions and compared their incidence of non-fatal myocardial infarction in the 90 days following initiation to their own baseline risk during the prior year. The results were striking. Across all ages, testosterone therapy was associated with a 36% increased risk of myocardial infarction. For men over 65, the risk more than doubled.

Age emerged as a powerful modifier. Younger men under 55 showed no significant increase in risk, but the pattern shifted progressively with advancing age. By the time men reached 75 and older, the rate ratio rose dramatically to more than three-fold. Such a trend suggests that testosterone therapy interacts with underlying vascular vulnerability, magnifying latent risks into clinical events.

Even more concerning was the finding in younger men with established heart disease. In this subgroup, the risk of myocardial infarction tripled following therapy initiation. By contrast, men under 65 without a history of heart disease did not experience an excess risk. These distinctions underscore a critical principle: testosterone therapy does not affect all men equally. Age and cardiovascular history profoundly shape the hazard profile, meaning that indiscriminate prescription is a recipe for preventable complications.

Mechanisms Behind the Risk

Associations are unsettling, but biological plausibility transforms suspicion into credibility. Testosterone therapy is not physiologically inert. It exerts a series of systemic effects that, while beneficial in some contexts, can easily tip into cardiovascular harm. Several mechanisms converge to explain the observed increase in myocardial infarction risk.

First, testosterone can induce polycythemia. Elevated hematocrit thickens the blood, increases viscosity, and promotes clot formation. This hyperviscous environment is fertile ground for thrombosis, including coronary artery occlusion. Second, exogenous testosterone has been shown to reduce HDL cholesterol while sometimes elevating LDL, altering lipid profiles in a manner unfavorable to cardiovascular health. Although the magnitude of change may seem modest, cumulative exposure amplifies the risk.

Third, testosterone influences platelet aggregation, increasing thromboxane receptor density and enhancing clotting potential. Additionally, its aromatization to estrogens introduces further prothrombotic effects. Estrogenic activity, whether in men or women, has long been associated with an increased risk of thrombotic events. Finally, testosterone may elevate blood pressure and contribute to vascular stiffness, compounding the traditional risk factors for myocardial infarction. Taken together, these mechanisms offer a coherent explanation for why testosterone prescriptions, particularly in older or cardiac-vulnerable men, so reliably translate into clinical events.

Clinical Implications for Older Men

The implications of these findings for older men cannot be overstated. In men over 65, testosterone therapy nearly doubled the risk of myocardial infarction, regardless of whether they had previously diagnosed heart disease. This uniformity suggests that age itself is a proxy for coronary vulnerability. Autopsy studies confirm that subclinical atherosclerosis is widespread in elderly men, even among those without a history of cardiovascular diagnoses. Thus, prescribing testosterone in this population effectively pours accelerant on smoldering embers.

For clinicians, the message is clear: testosterone therapy in older men must be approached with extreme caution, if at all. The risk-benefit balance tilts heavily toward harm, given that the primary benefits—slightly improved strength, libido, or mood—are modest compared to the catastrophic consequence of myocardial infarction. Importantly, in men who discontinued therapy after their first prescription, the risk returned to baseline within 90 to 180 days, reinforcing the drug’s causal role rather than confounding by background disease.

Patients often ask whether short-term therapy might be safer. The evidence suggests otherwise. The increased risk manifests rapidly within the first three months of treatment, highlighting that adverse cardiovascular consequences are not merely the result of long-term accumulation but of immediate physiologic changes. In this sense, testosterone therapy in older men resembles playing a dangerous game of chance, where even brief exposure may trigger irreversible outcomes.

Considerations for Younger Men

The story in younger men is more nuanced. For those under 65 without pre-existing cardiovascular disease, testosterone therapy did not significantly elevate myocardial infarction risk. This suggests that in carefully selected patients—true hypogonadal men with normal vascular health—testosterone may be relatively safe in the short term. However, this should not be misconstrued as a blanket endorsement.

The caveat lies in younger men with a history of heart disease. In this group, testosterone therapy nearly tripled the risk of myocardial infarction. The presence of damaged vasculature, endothelial dysfunction, or prior ischemic events likely creates a substrate vulnerable to testosterone’s prothrombotic and hemodynamic effects. Such patients may present as younger and ostensibly resilient, but their cardiac histories render them as fragile as their older counterparts.

The clinical challenge is therefore one of differentiation. Not all younger men are suitable candidates for testosterone therapy, and physicians must resist the temptation to equate youth with invulnerability. Comprehensive cardiovascular assessment should precede any prescription. If a patient has a history of ischemic heart disease, angina, or arrhythmias, testosterone therapy should be considered high-risk and approached with great reluctance.

Limitations and Counterarguments

No study is without limitations, and balanced interpretation requires acknowledgment of uncertainties. The data linking testosterone therapy to myocardial infarction come from administrative health databases rather than randomized controlled trials. Diagnoses of myocardial infarction were derived from medical coding rather than adjudicated events, although prior research confirms that such coding is generally reliable.

Another limitation lies in the absence of information on testosterone levels prior to prescription. It remains unknown whether the men studied had biochemical hypogonadism or were prescribed therapy on the basis of symptoms alone. Additionally, the study focused on non-fatal myocardial infarction, leaving open questions about fatal events or other cardiovascular outcomes such as stroke or arrhythmia.

Critics argue that low endogenous testosterone is itself associated with increased cardiovascular mortality, suggesting that therapy might in some cases be protective. Indeed, observational studies have shown an association between hypogonadism and poor cardiac outcomes. Yet, as epidemiologists emphasize, correlation is not causation. Low testosterone may be a marker of chronic illness rather than a cause. More importantly, exogenous testosterone alters physiology in ways that do not simply restore natural balance but instead impose supraphysiologic stresses. Until randomized trials definitively address these issues, the precautionary principle must prevail.

Practical Guidance for Clinicians

In navigating this complex terrain, clinicians require pragmatic strategies. First, testosterone therapy should only be considered in men with unequivocal hypogonadism, confirmed by repeated biochemical testing. Vague symptoms without laboratory evidence are insufficient justification for exposing patients to cardiovascular risk.

Second, age and cardiovascular history must be central to decision-making. For men over 65, or those of any age with documented heart disease, the risks of testosterone therapy substantially outweigh the benefits. If prescribed at all, such therapy must occur under close surveillance, with informed consent that explicitly acknowledges the increased risk of myocardial infarction.

Third, clinicians should monitor hematocrit, lipid profiles, and blood pressure regularly in patients receiving testosterone. Early identification of adverse trends allows for dose adjustment or discontinuation before catastrophic events occur. Finally, physicians must engage in transparent discussions with patients. Many men pursue testosterone for improved energy or sexual function, unaware of the potential consequences. Presenting the data honestly empowers them to make informed decisions rather than succumbing to glossy advertisements promising eternal youth.

Public Health and Policy Considerations

Beyond individual practice, the testosterone debate carries broad implications for public health policy. Prescription rates for testosterone have increased exponentially in the United States and beyond, fueled not only by medical practice but also by cultural narratives equating masculinity with hormonal supplementation. If current trends continue, even a modest relative risk of myocardial infarction will translate into thousands of preventable cardiac events annually.

Regulatory agencies face the challenge of balancing access with safety. Warnings about cardiovascular risk must be incorporated into prescribing guidelines and product labeling. Education campaigns targeting both physicians and patients are essential to counteract the pharmaceutical industry’s marketing influence. Moreover, the urgent call for randomized controlled trials cannot be overstated. Observational studies, while valuable, cannot resolve lingering uncertainties about long-term risks, dose-response relationships, and differential effects across patient subgroups.

In the meantime, restraint is prudent. Medicine must not become complicit in normalizing testosterone therapy as a lifestyle drug divorced from genuine medical necessity. Just as society has grown wary of indiscriminate opioid prescribing, so too must it critically appraise the indiscriminate use of hormones with potentially grave consequences.

Conclusion

Testosterone therapy is no longer a niche intervention for a handful of hypogonadal men. It has become a mainstream prescription, often untethered from rigorous diagnostic criteria. Yet with widespread use comes responsibility, and the evidence is increasingly difficult to dismiss: testosterone therapy raises the risk of non-fatal myocardial infarction, particularly in older men and in younger men with existing heart disease.

The biological mechanisms underpinning this association are compelling, ranging from polycythemia to platelet activation and estrogen conversion. The risk emerges rapidly, within weeks of therapy initiation, and subsides once treatment stops. Such temporality, combined with consistency across studies, underscores the likelihood of causality.

For clinicians, the message is sobering. Testosterone may restore libido and muscle strength, but it can just as easily precipitate a heart attack. Careful patient selection, rigorous monitoring, and candid discussions of risk are not optional—they are the minimum ethical obligations. Until randomized trials provide definitive answers, testosterone therapy must be prescribed with restraint, skepticism, and above all, a keen awareness that vitality is meaningless if purchased at the cost of cardiac survival.

FAQ

1. Is testosterone therapy safe for healthy younger men without heart disease?

In younger men without cardiovascular disease, short-term studies show no significant increase in myocardial infarction risk. However, long-term safety remains unproven, and careful monitoring is essential.

2. Why does testosterone increase the risk of heart attacks in older men?

Older men are more likely to harbor undiagnosed coronary artery disease. Testosterone promotes clotting, raises blood viscosity, and alters lipid profiles, all of which magnify the vulnerability of aging arteries.

3. Should men with heart disease ever receive testosterone therapy?

Current evidence strongly cautions against it. In men with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, testosterone therapy nearly triples the risk of myocardial infarction. The potential benefits rarely justify this danger.