Radical cystectomy remains the cornerstone treatment for muscle-invasive bladder cancer and selected cases of high-risk non–muscle-invasive disease. Despite refinements in surgical technique, perioperative care, and the use of enhanced recovery pathways, the procedure carries a significant burden of morbidity. Patients often face profound challenges: physical deconditioning, nutritional deficits, stoma-related adaptation, sexual dysfunction, and enduring psychological stress. Against this backdrop, the concept of structured prehabilitation and rehabilitation has emerged as a means to improve outcomes beyond the operating room.

This article explores the role of perioperative supportive strategies in radical cystectomy, critically examining evidence on their effects on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), functional recovery, and long-term survivorship. We also reflect on the strengths and limitations of current data, with an eye to future directions.

Radical Cystectomy: A High-Impact Surgical Journey

Radical cystectomy is not a single operation; it is a trajectory that spans preoperative preparation, perioperative stress, and postoperative recovery. Patients are often older, frailer, and burdened with comorbidities. The removal of the bladder, along with lymphadenectomy and urinary diversion, results in a cascade of physiological and lifestyle changes.

From a medical perspective, morbidity manifests as wound complications, infection, thromboembolic events, ileus, and cardiopulmonary issues. From the patient’s perspective, the consequences are even broader: fatigue, anorexia, loss of independence, altered body image, and a forced negotiation with new urinary and sexual function. Thus, cystectomy represents both a surgical and a psychosocial stress test.

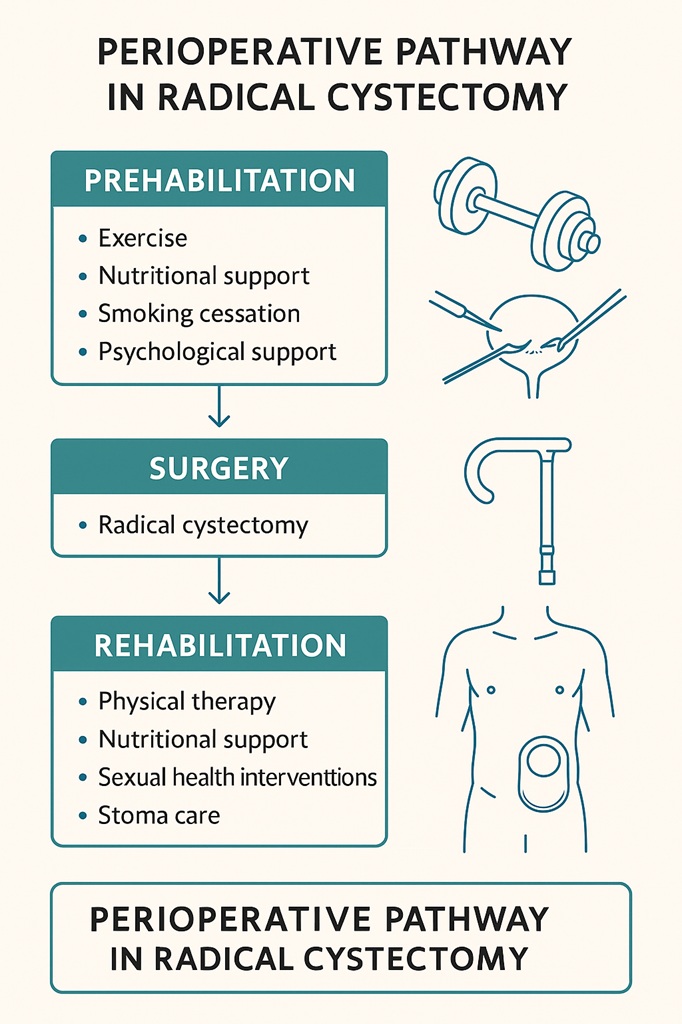

It is in this context that prehabilitation (interventions before surgery) and rehabilitation (interventions after surgery) have been proposed as systematic strategies to improve outcomes. Unlike ad hoc lifestyle advice, these approaches are structured, multidisciplinary, and targeted to mitigate the predictable sequelae of cystectomy.

The Rationale for Prehabilitation

Prehabilitation rests on a deceptively simple premise: a fitter patient will withstand surgical stress better and recover faster. Yet fitness is multidimensional. It encompasses cardiorespiratory reserve, nutritional adequacy, muscular strength, and psychological readiness.

In bladder cancer, the preoperative window—often several weeks between diagnosis, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and surgery—presents a unique opportunity. Rather than passively awaiting surgery, patients can actively enhance their resilience. This proactive philosophy mirrors the training of an athlete before competition, except here the “competition” is the physiologic challenge of cystectomy.

Interventions typically include aerobic and resistance exercise, nutritional supplementation, smoking and alcohol cessation, and psychological support. Importantly, prehabilitation is not a luxury but rather a potential necessity, given the steep recovery curve faced by these patients.

Exercise and Physical Conditioning

Physical inactivity is a silent accomplice to poor surgical outcomes. Bed rest and deconditioning reduce cardiorespiratory reserve, impair wound healing, and predispose to thromboembolism. Conversely, structured exercise programs aim to enhance oxygen delivery, improve muscular function, and support faster mobilization postoperatively.

Studies investigating exercise-based prehabilitation in cystectomy show encouraging signals. Patients engaged in aerobic and resistance training demonstrate improved six-minute walk distance, better postoperative ambulation, and in some reports, shorter hospital stays. Beyond physical capacity, exercise conveys psychological benefits: reduced anxiety, enhanced confidence, and an improved sense of agency.

However, heterogeneity abounds. Exercise regimens vary from supervised physiotherapy to home-based walking programs. Adherence is often underreported, and trials remain underpowered. While consensus on the optimal “dose” of exercise is lacking, the biological plausibility and safety profile strongly support its role.

Nutritional Optimization

Malnutrition is a formidable adversary in radical cystectomy. Between cancer-induced cachexia, reduced oral intake, and catabolic effects of chemotherapy, many patients approach surgery in a precarious nutritional state. Malnutrition correlates with infection, delayed wound healing, prolonged ileus, and increased mortality.

Nutritional prehabilitation seeks to reverse this trajectory. Strategies range from high-protein oral supplements to immunonutrition formulas enriched with arginine, omega-3 fatty acids, and nucleotides. The goal is not merely caloric adequacy but modulation of inflammatory and immune responses.

Evidence indicates that patients receiving targeted nutritional support experience reduced postoperative complications and, in some trials, improved survival. Yet gaps remain: nutritional screening tools vary, and adherence can be limited by poor appetite or treatment-related nausea. What is clear, however, is that ignoring nutrition is not an option—it is as essential as antibiotics or thromboembolism prophylaxis in the perioperative pathway.

Smoking and Alcohol Cessation

Tobacco use is the leading risk factor for bladder cancer and a modifiable determinant of surgical outcomes. Continued smoking before surgery increases the risk of pulmonary complications, delayed healing, and anastomotic leaks. Similarly, excessive alcohol intake contributes to cardiopulmonary instability, infections, and poor wound healing.

Smoking cessation interventions, even when initiated just weeks before cystectomy, significantly reduce perioperative complications. The “teachable moment” of a cancer diagnosis can be leveraged to promote abstinence. Alcohol reduction programs, although less studied in cystectomy specifically, hold parallel benefits.

In essence, prehabilitation is an opportunity not only to prepare for surgery but also to catalyze long-term lifestyle changes that reduce recurrence and improve overall survival.

Psychological Preparation

The psychological toll of bladder cancer and radical cystectomy cannot be overstated. Anxiety, depression, and fear of body image changes accompany the preoperative period. These emotions are not trivial—they directly impact adherence, recovery, and long-term HRQoL.

Psychological prehabilitation includes counseling, peer support groups, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and structured education about surgery and stoma care. Evidence suggests that patients who feel informed and supported enter surgery with reduced anxiety and recover with greater confidence.

The challenge remains scalability: not every center can provide in-depth psychological services. Nevertheless, even brief, structured preoperative counseling can improve outcomes by reframing the surgical journey as manageable rather than overwhelming.

Postoperative Rehabilitation: Beyond Survival

Surviving cystectomy is not the same as recovering from it. Rehabilitation focuses on restoring function, independence, and dignity. It encompasses physical therapy, nutritional reinforcement, sexual health interventions, and stoma management training.

Physical rehabilitation builds upon prehabilitation, ensuring that gains in conditioning are not lost to prolonged bed rest. Early mobilization protocols, guided physiotherapy, and outpatient exercise programs form the backbone. Nutritional rehabilitation continues the work of rebuilding lean body mass and preventing sarcopenia.

Perhaps most critically, rehabilitation addresses the “new normal.” Patients must learn to manage urinary diversion (ileal conduit, continent reservoir, or neobladder), cope with altered sexual function, and navigate the psychological impact of cancer survivorship. Rehabilitation is thus holistic, bridging medicine, psychology, and social care.

Sexual Function and Intimacy

Sexual dysfunction after cystectomy is common, owing to nerve sacrifice, hormonal changes, and psychological factors. For men, erectile dysfunction is nearly universal; for women, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, and altered orgasmic function are prevalent.

Rehabilitation strategies include phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, intracavernosal injections, vacuum devices, and in selected cases, surgical implants. For women, interventions focus on vaginal dilators, lubricants, and hormonal support. Importantly, sexual counseling helps normalize expectations and foster communication between partners.

Despite being a predictable complication, sexual rehabilitation is often underemphasized. Yet evidence shows that proactive interventions significantly improve quality of life. The message is clear: restoring intimacy is not optional but integral to recovery.

Stoma and Urinary Diversion Care

The learning curve of living with a stoma is steep. Patients must master appliance changes, skin care, and fluid balance. Complications such as leakage, dermatitis, and infections can undermine confidence and restrict social participation.

Structured stoma education, initiated preoperatively and continued postoperatively, reduces complications and empowers patients. Specialist stoma nurses are invaluable in this process, offering both technical training and emotional reassurance. Peer support groups further normalize the experience, reducing isolation.

For patients with continent diversions or neobladders, rehabilitation includes teaching catheterization, bladder training, and recognition of complications. The transition is rarely smooth but becomes manageable with structured support.

Evidence on Health-Related Quality of Life

The ultimate yardstick of prehabilitation and rehabilitation is not just complication rates but HRQoL. Systematic reviews reveal that perioperative supportive interventions improve domains of physical function, fatigue, and emotional well-being. Patients undergoing structured programs report earlier return to baseline activity and greater satisfaction with care.

However, evidence is far from definitive. Trials are small, heterogeneous, and often limited by methodological weaknesses. Endpoints vary, with some focusing on HRQoL scales, others on walk tests, and still others on complication rates. The lack of standardization hampers meta-analysis and guideline formulation.

Nonetheless, the signal is consistent: structured perioperative interventions confer meaningful benefits, even if the precise magnitude remains uncertain.

Barriers and Future Directions

Despite their promise, prehabilitation and rehabilitation face barriers to widespread adoption. These include resource constraints, variability in protocols, patient adherence, and lack of standardized outcomes.

Future research must address these gaps by:

- Conducting large, multicenter randomized trials with standardized protocols.

- Integrating digital tools such as wearable fitness trackers and telemedicine platforms.

- Expanding psychosocial and sexual rehabilitation services.

- Exploring cost-effectiveness to justify system-wide implementation.

Ultimately, perioperative supportive care in cystectomy should evolve from “optional extras” to standard of care, embedded within enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathways.

Conclusion

Radical cystectomy is among the most demanding procedures in urologic oncology. While surgical skill and oncologic control remain central, the patient’s journey extends far beyond the operating theater. Prehabilitation and rehabilitation offer a structured framework to enhance resilience, mitigate complications, and restore quality of life.

The evidence, though imperfect, consistently points toward benefit. The challenge for the medical community is not whether to adopt these strategies, but how best to deliver them at scale, equitably, and with measurable outcomes. Patients deserve not just survival, but recovery in the fullest sense of the word.

FAQ

1. What is the main goal of prehabilitation before radical cystectomy?

The aim is to improve a patient’s physical, nutritional, and psychological resilience before surgery, enabling them to better withstand surgical stress and recover more effectively afterward.

2. Does rehabilitation after cystectomy only involve physical therapy?

No. Rehabilitation is comprehensive, covering physical therapy, nutritional support, stoma care, sexual health interventions, and psychological counseling. It addresses both medical and quality-of-life dimensions.

3. Is there strong evidence that these programs improve outcomes?

Evidence shows consistent benefits in physical function, reduced complications, and improved HRQoL, though studies remain heterogeneous and often small. Larger standardized trials are needed, but the current data support their clinical value.