Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is more than a private inconvenience; it is a public health issue with significant psychological, relational, and medical consequences. Globally, it affects millions of men, and its prevalence is steadily rising due to aging populations, increasing rates of diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. In Somalia, the condition takes on unique dimensions. Limited access to specialized urological care, absence of strong regulatory frameworks, and heavy reliance on community pharmacies create a situation where pharmacy technicians, rather than physicians, often become the first and sometimes the only point of contact for men seeking help with sexual dysfunction.

The Somali healthcare system, fragmented by years of conflict and underfunding, relies heavily on private drug outlets and pharmacies to deliver frontline care. For conditions such as erectile dysfunction, where cultural stigma limits open discussion with physicians, men often bypass formal medical consultations and self-medicate. The availability of sildenafil and other PDE5 inhibitors without prescription further entrenches this practice. It is therefore essential to assess what community pharmacy technicians know, how they perceive erectile dysfunction, and how they dispense and counsel in real-world practice.

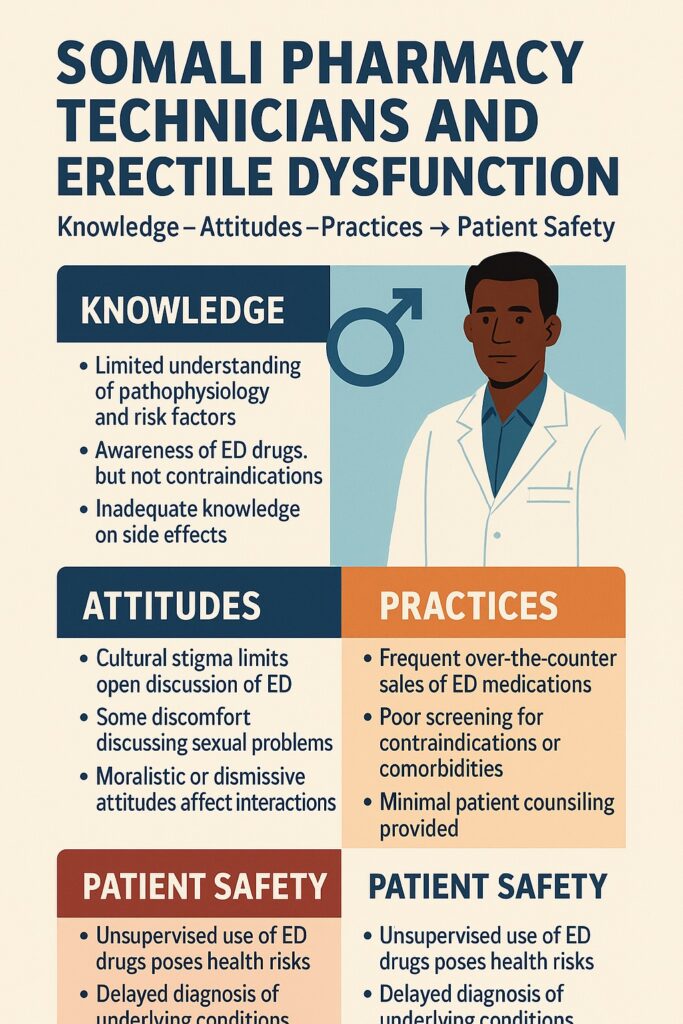

A recent cross-sectional study conducted in Somalia sought precisely this. By investigating the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) of community pharmacy technicians regarding erectile dysfunction, the study illuminates not only gaps in training but also systemic vulnerabilities in the Somali healthcare environment. The findings hold implications for patient safety, rational drug use, and broader public health policy.

The Somali Context: Pharmacies as Primary Healthcare Providers

To understand the significance of this study, one must first appreciate the Somali healthcare landscape. The country faces a shortage of physicians, particularly specialists such as urologists and endocrinologists. For many citizens, healthcare access is mediated through private community pharmacies, which are more numerous, affordable, and geographically accessible than hospitals or clinics.

In this model, pharmacy technicians, often trained only through diploma programs, assume a role far beyond dispensing. They diagnose, recommend, and even prescribe treatments, including for sensitive conditions like erectile dysfunction. Men, reluctant to discuss sexual problems openly with physicians due to cultural and social stigma, find pharmacies a more discreet alternative. This reliance, however, raises pressing questions: Do pharmacy technicians possess adequate knowledge of ED? Do they approach patients with appropriate attitudes? And do their practices align with safe and evidence-based standards?

The Somali case, therefore, becomes not just about sexual health but about how fragile health systems rely on paramedical cadres, and how this affects vulnerable patients.

Knowledge: Understanding of Erectile Dysfunction and Its Treatments

The study revealed that pharmacy technicians in Somalia demonstrate mixed levels of knowledge about erectile dysfunction. While most had heard of the condition and were aware of sildenafil and related PDE5 inhibitors, significant gaps emerged in their understanding of pathophysiology, risk factors, and contraindications.

Technicians frequently recognized psychological stress, aging, and diabetes as contributors to ED, but fewer could accurately explain the vascular basis involving nitric oxide and cGMP signaling. This is not surprising given their limited medical training, but it is problematic in practice. Without a clear grasp of underlying mechanisms, technicians may underestimate the importance of managing comorbidities such as hypertension or cardiovascular disease, conditions intimately tied to ED both as causes and as contraindications for PDE5 inhibitor use.

Perhaps most concerning was the limited awareness of contraindicated drug interactions, particularly with nitrates. Combining nitrates with sildenafil can lead to catastrophic hypotension, yet a notable proportion of technicians did not mention this risk. Knowledge of side effects was similarly incomplete: while headache and flushing were commonly cited, fewer mentioned visual disturbances, priapism, or the cardiovascular risks relevant to Somali patients with limited access to emergency care.

Thus, while technicians were aware of ED medications in name, their knowledge was superficial. This shallow understanding leaves patients vulnerable to unsafe self-medication practices, a risk magnified in settings with little regulatory oversight.

Attitudes: Stigma, Sensitivity, and Professionalism

Knowledge alone does not determine patient outcomes. The way pharmacy technicians perceive erectile dysfunction and interact with affected men plays an equally critical role. The study revealed a complex interplay of professionalism, cultural attitudes, and stigma.

On the positive side, many technicians expressed willingness to counsel patients with ED, suggesting an openness to engage in conversations that are often taboo. They acknowledged the psychosocial burden ED imposes and indicated empathy toward men seeking help. However, attitudes were far from uniformly professional. Some technicians trivialized ED as a mere lifestyle issue, while others carried moralistic undertones, implicitly blaming patients for their condition.

Cultural stigma surrounding sexual health in Somalia compounds the problem. ED is often viewed as a shameful weakness rather than a medical condition. This stigma infiltrates pharmacy practice: some technicians admitted discomfort discussing details of sexual function, leading to superficial or rushed consultations. Such attitudes can discourage patients from disclosing comorbidities or medication histories, which are crucial for safe dispensing.

In short, while a subset of Somali pharmacy technicians demonstrated constructive attitudes, stigma and moral judgment remain barriers to optimal patient interaction. Changing these attitudes will require not only clinical training but also broader cultural sensitization.

Practices: Dispensing Habits and Patient Counseling

Perhaps the most striking findings of the study lay in actual dispensing practices. In Somalia, sildenafil and other PDE5 inhibitors are readily available over the counter, and community pharmacies frequently sell them without prescription.

Pharmacy technicians reported that they commonly dispense sildenafil upon direct patient request, with minimal questioning. Only a minority systematically assessed comorbidities such as cardiac disease or concurrent nitrate use. Even fewer asked about psychosocial stressors or lifestyle factors contributing to ED. Counseling, when provided, was often limited to instructions on dosage, with little emphasis on potential side effects, interactions, or the need for medical follow-up.

This practice environment reflects a dangerous normalization of unsupervised PDE5 inhibitor use. Men in Somalia, seeking quick relief, may take these drugs without understanding the risks. Technicians, pressured by patient expectations and business imperatives, often comply without applying clinical judgment. The study also revealed cases of technicians recommending PDE5 inhibitors for men without clear ED, essentially for recreational use—further increasing risks of abuse, dependency, and adverse effects.

Such practices underscore the urgent need for regulation and professional development. Without intervention, Somali men remain at risk of inappropriate drug use, masked cardiovascular disease, and avoidable complications.

Public Health Implications

The findings carry broad implications beyond individual patients. At a population level, the unregulated use of sildenafil and similar drugs threatens to:

- Mask underlying disease: Erectile dysfunction can be an early marker of cardiovascular pathology. Reliance on over-the-counter PDE5 inhibitors delays diagnosis of serious systemic illness.

- Increase adverse drug events: Inadequate screening for contraindications exposes men to risks of hypotension, arrhythmias, and priapism, with limited emergency services to provide timely care.

- Promote drug misuse: Widespread recreational use of ED medications can normalize unsafe practices, leading to tolerance, dependence, and potentially harmful cultural trends.

- Strain fragile health systems: Complications arising from misuse impose additional burdens on Somalia’s already stretched healthcare infrastructure.

In a setting where resources are scarce and regulation is weak, the unmonitored dispensing of ED drugs is a public health hazard. It illustrates the broader tension between accessibility and safety in pharmacy-driven health systems.

Path Forward: Education, Regulation, and Training

The study’s findings are not merely descriptive—they point to actionable solutions. Addressing the knowledge, attitude, and practice gaps among Somali pharmacy technicians requires a multifaceted approach:

First, education. Structured training programs must equip technicians with accurate knowledge of ED pathophysiology, risk factors, and drug interactions. Continuing education modules could be designed in collaboration with universities and professional associations, ensuring technicians remain updated.

Second, regulation. Policymakers must enforce stricter rules on the sale of PDE5 inhibitors, requiring prescriptions for purchase. While challenging in Somalia’s decentralized health system, even partial regulation could reduce misuse and encourage medical consultation.

Third, professional development in communication skills. Pharmacy technicians need training not only in clinical facts but also in patient-centered counseling. Sensitivity to stigma, confidentiality, and cultural barriers can transform interactions, making pharmacies safer spaces for men with ED.

Finally, integration with broader healthcare services. Pharmacies should serve as referral hubs, guiding patients with ED to clinics for cardiovascular screening, hormonal evaluation, or psychological support. In this way, pharmacy technicians can complement, rather than replace, medical practitioners.

Conclusion

Erectile dysfunction in Somalia is not merely a medical issue; it is a mirror reflecting the state of the health system. In the absence of strong regulation and widespread specialist care, community pharmacies have become de facto providers for men with ED. This reality places enormous responsibility on pharmacy technicians, whose knowledge, attitudes, and practices directly shape patient outcomes.

The recent Somali study makes clear that while technicians are accessible and willing to help, their knowledge is limited, their attitudes shaped by stigma, and their practices often unsafe. Left unchecked, these gaps risk perpetuating misuse of PDE5 inhibitors, masking systemic disease, and endangering men’s health.

Yet the path forward is hopeful. With targeted training, cultural sensitization, and regulatory support, Somali pharmacy technicians could become valuable allies in addressing ED, guiding men not only to symptom relief but also to comprehensive care. In a country where health systems face profound challenges, even incremental improvements in pharmacy practice could yield disproportionate benefits for male reproductive and cardiovascular health.

FAQ

1. Why do Somali men often seek treatment for erectile dysfunction at pharmacies instead of hospitals?

Cultural stigma, lack of specialists, and limited access to healthcare facilities lead many men to seek discreet help directly from pharmacies.

2. Are PDE5 inhibitors like sildenafil safe when purchased over the counter?

Not always. While generally effective, they carry serious risks when used without medical supervision, particularly in men with heart disease or those taking nitrates.

3. What changes are needed to improve ED management in Somalia?

Training programs for pharmacy technicians, stricter regulation of PDE5 sales, and stronger referral systems to link men with formal medical evaluation are essential.